🌐🌐🌐

Mahaneela, Great Blue

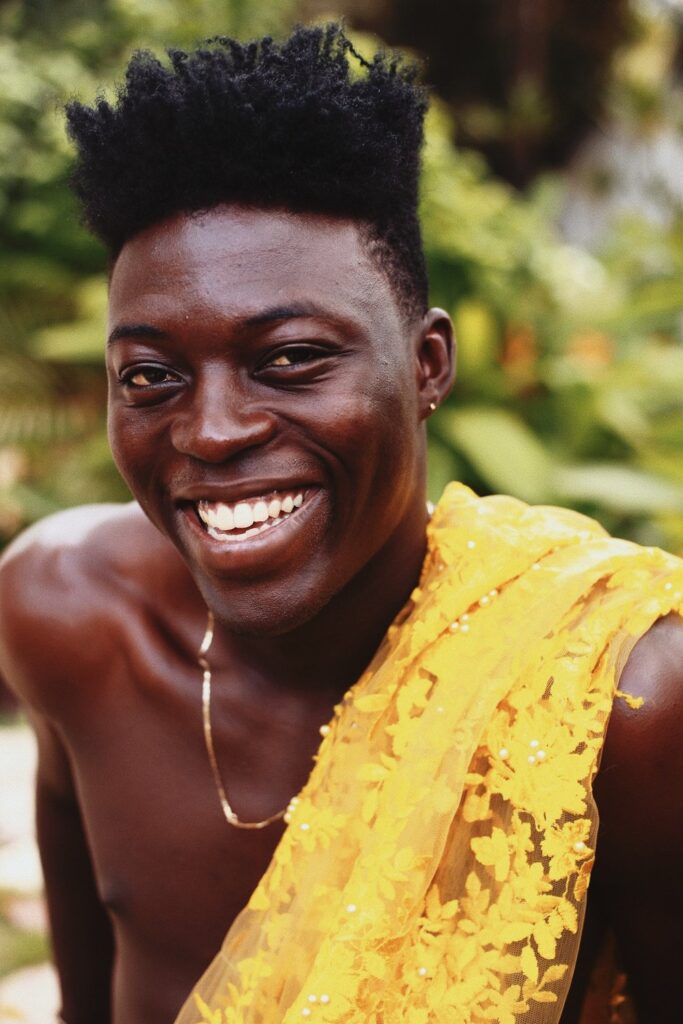

Brooklyn-based freelance creative Mahaneela is the only person in the world with her name – which translates to “Great Blue.” It is the epitome of a lifelong mission she’s carved out for herself to do things in a way that only she can. (NOTE: All media counterparts to the article are either of, or shot/directed by, Mahaneela.)

SAMUEL HYLAND

Don Miguel Ruiz’s The Four Agreements is a written code of conduct for self-help deeply rooted in ancient Toltec wisdom. It’s also one of the creative freelancer Mahaneela’s favorite titles. “That’s just something I’ve always gone back to,” she tells me in a Zoom call, asked whether any written work has had a major impact on her life. “But I wouldn’t say that that’s the defining book of my life. It’s only quite new for me to be reading non-fiction books — growing up, I used to read loads of fiction. And then true crime. I loved true crime. I used to just go right through those in one day. But Four Agreements is a book I still feel I have to read every few years to re-align. It just needs to be read again and again and again.” Aside from fiction and true crime, The Four Agreements is a story told in four titular chapters – the “agreements” themselves – where rather than being hidden behind plots, characters, and story arcs, expressed themes lie explicitly therein: Agreement 1: Be Impeccable With Your Word. Agreement 2: Don’t Take Anything Personally. Agreement 3: Don’t Make Assumptions. Agreement 4: Always do your best.

Right now, Mahaneela seems to bask in the nirvana-esque reality made possible by adhering to such guidelines. Coming off of a rain-filled foray to visit family in her hometown of London, England, she’s chilling in an Airbnb on Jamaica’s Western tip, puffing on a spliff, taking in the greenery, living in the moment. When the ability to look back at one’s own accomplishments and relax is brought up in conversation, she does not hesitate to turn her camera around, declaring with glee: “I mean, look at where I am right now!” The terrain shown on-screen is a vast expanse of sunlight and swaying palm trees. There are no other human beings in sight.

It’s nearly stupefying that years before, the liberated lifestyle she leads today was widely obstructed by a status-quo of normalcy that especially manifested itself in her education. Her first two years as a philosophy major at the University of London saw her struggle to balance knee-deep foundations in creative industries with coursework that loomed on a daily basis. Regularly, she traveled to cities including Los Angeles and New York to work with musicians amidst raging uni semesters. She had additionally co-founded a culture magazine, Cozy Global, for which she stayed up until five o’clock in the morning on several occasions building and updating an accompanying website, on top of producing consistent content. “It was getting to a point where there were opportunities that were coming that I felt like school was taking me out of,” she says.

So, one morning, she woke up and decided to drop out.

“One day, I was just like I don’t want to do this. I knew I didn’t want to do it the whole time; I was leaving things to the last minute- I was still doing fine, but I was causing myself unnecessary stress. It felt like a chore. It came to a place where I was like I just don’t want this to feel like a chore anymore.”

After talking things over with her mother, whose support she is adamant about having needed then, she wrote an email to the institution expressing that she no longer wished to attend. They did not fight to try to keep her enrolled. The laissez-faire of the university happens to be one line on a laundry list of differences she cites between college experiences here in the United States and in the United Kingdom. “University’s a bit different to American (college), where you, like, know your teachers and whatnot. It wasn’t really like that. You just go to lectures and that’s it. You’re not in a campus, it’s not, like, sororities, or things like that at all. It’s just adults who live in London who are just going to school.” She stretches an arm back to fiddle with her ponytail, contemplating a bit deeper. “Not on a daily basis either; I only had, say, two lectures a week or something?” There’s an obvious shift in her tone that makes it very clear that growing jaded was inevitable. If, in America, over half of college students drop out with access to campuses, sororities, and activities, one could only imagine the persistence balancing a fledgling artistic career with a more muted university experience requires. “I just didn’t know where I fit into it,” she says of the situation, now readjusting in her sitting position. Her eyebrows rise matter-of-factly. “It is what it is.”

Then, with the kind of unrestrained laughter that comes exclusively from success, Mahaneela muses that this is simply the spontaneous kind of person she is. And she’s right. Both in London and Brooklyn, her creative resumé leaves a footprint that insinuates the perfect concoction of curiosity and impulse: creative director, DJ, music writer, consultant, photographer, videographer, XL Recordings Communication & Curation manager, film director, blogger, FKA Twigs management team member, marketer, public speaker. The ability to remain invested in such a widespread gamut comes as one of many results of her simple desire to learn about the world she lives in: a desire she satisfies through traveling the globe nonstop for both professional and personal inclinations. It is in this way that it’s no surprise for her not to be remotely rattled about having moved across the ocean to Brooklyn from her lifelong London home earlier this year. Where fear would take form, she channels inspiration. Where there would be apprehension, she generates activity. In place of homesickness, there is a resolve that, given the globetrotter she has grown into in lifestyle, she will be back home soon enough – but until then, the only possible course of action is to find home where she happens to be.

“Whether or not people know who I am, I’m always going to be consistent, doing what I’m doing.”

“In a way, I’ve gotten to know in a different sense a bit more of local Brooklyn: My neighborhood, the people I see every day, my neighbors . . . stuff like that is a very different experience to London. There, you don’t tend to know your neighbors, and your friends all live quite far apart from each other. Whereas, in New York – definitely in Brooklyn – even Keith (Charles) lives down the street from me.” Her eyes widen with what looks to be a new thread of intrigue awakened by vivid reimagination. “We all live really close to each other. I think that’s really nice, to have, like, friends and like-minded people super close,” she says, as a smile creeps onto her face.

After this answer, the topic of conversation briefly shifts to whether there is a creative synergy to be found in simply coming across new people. Her work loudly suggests that she must be a people person. On top of working with artists like Steve Lacy and Sampha, she does camera work that requires that another human always be at the other end of her personal territory (“I take inspiration from people because everything I do is related to, like, people)”. And these are, by no means, people of just one category. They’re people representing demographics spanning the entirety of planet Earth, living the epitomes of nations carried forth by centuries of tradition, encasing within their blood decades of life originating in corners of the world yet to be tread upon by many. For Mahaneela, being vested in the ongoing story of humanity at each setting that breeds it births an uncanny ability to resonate with tokens of various cultures within the very folds of ones that are miles – or even an ocean – away.

“There’s similarities. Like if you go to Queens, it feels like parts of London, which is really cool. But then also meeting Dominican people, Puerto Rican people- I just don’t have that kind of network with people in London,” she tells me. “So it’s just interesting to see different communities and their cultures. That’s like, the norm there, because there’s just so many people from that place. But I have never before, until moving there, met people from Puerto Rico, or seen when it’s Puerto Rican Day, where they have all the flags and everything. That’s all new to me. And that’s inspiring for sure.”

Something that brings Mahaneela’s reception of global mannerisms even more clear in focus is the swiftness with which she rails off similarities between places she’s visited, upon being asked for examples of positive traveling recollections. Resting face-up atop several cushions on a couch inside now, she speaks with constantly moving eyes about the origins of Indians in Mauritius. In the early 19th Century, they were brought to the country as indentured workers. Six to seven generations of them remained on the mini-continent; but, what she finds interesting is that they evidently held on to certain aspects of their Indian culture for the full length of this period. “Even though they’ve created this new African-Mauritian identity, these remnants from Indian culture- you would be seeing certain temples like That could be in India. But I’m in Africa. That’s really interesting to me.”

Next up on her list is the flip side of it: how various cultures have manifested their influences in India itself. India is one of several nations in which Mahaneela finds heritage; aside from being of Indian descent, she’s Ghanaian, Jamaican, and Ugandan, with the added touch of having lived in the United Kingdom. She speaks of India with eyebrows that jump up and down, eyes that dart left and right, hands that motion vividly across the camera frame. The fascinating thing about this country, to her, is how a stark Christianity remains prevalent centuries after the earliest Jesuit missions trips implemented the religion there in the first place – yet, existing at the same time is a strong Hinduism that does not combat, but compliment what deep Christian nuances a common society is to be shared with. “Just going to India, being in the town there, and seeing how everyone there was Christian. They had Christian churches, Anglican churches with white Jesuses. But then they still had Puja flowers, and offerings that are so deep within the Indian culture that even though people were still Christian – Christianity was the biggest religion in that town – there were still these cultural elements.”

The risk, when it comes to merging cultural gaps the way Mahaneela does, is the unintentional reenactment of colonial mentalities. It’s okay to be curious, but the curiosity becomes toxic when it’s insensitive.

In an Instagram video she shared in collaboration with NARS Cosmetics earlier this summer, she spoke about what ideal honesty ought to look like in documentation of foreign life. “When I do travel, I make a big effort to really immerse myself,” she said. “Authenticity, to me, is about making sure that the people who are from a specific country or culture are the ones telling their story.”

When I ask where the line is drawn between appreciation and inadvertent appropriation, she’s quick to challenge my use of the latter term.

“I wouldn’t say it’s appropriation to go somewhere and not ask the details.” She takes a moment to readjust her sitting position – presently, she’s laid out sideways on the couch, a lazy half-fist propping her resting head into the camera frame. “When you’re in the act of appropriating, you’re using something without giving proper credit to its source for your own benefit. So that would be, for example, like if I was to go to Namibia and find out about this amazing textured pattern or whatever – then start my own clothing line without telling anyone that that’s the inspiration. Just copying it, for my own good. That’s appropriating someone’s culture.”

The more common representation of colonizer-esque activity, she explains, is the widespread umbrella of cultural ignorance. Examples she lists include western media outlets sending white photojournalists to spiritual diasporic villages wherein photography is sacrilegious, brands flying papparazzo out to Muslim areas where women are uncomfortable around masculine figures, and even the typical tourist venturing around, snapping photos of villagers without consent of any form. The common factor she cites in all of these scenarios is that they all fall on one stick – the far end of which is the appropriation I brought up earlier on.

There’s only one me. I can only do things in my way, you know?

Ideas around cultural appreciation-slash-appropriation festered into a worldwide conversation this past June, when the deaths of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbury, among others, re-ignited international talks about race relations in America. Suddenly, there was an interest in the creative work people of color had been doing for centuries. And most artists highlighted had been invested in their labor for years without recognition. It quickly grew commonplace for comprehensive lists – “Black-owned businesses to support,” “Black creatives to follow,” “POC musicians to stream,” etc. – to circulate social media platforms, seeking to rally consumers behind the demographic that had obviously been at a disadvantage, almost as if to undo years of marginalization and disenfranchisement.

One morning within that period, Mahaneela woke up to over ten thousand new Instagram followers. Her name, she discovered later, had appeared on several of the lists.

She felt the need to formally introduce herself. The urge to do so was addressed in a lengthy Instagram caption, written underneath a ten-picture slideshow sampling highlights from previous work.

“Wow so i’ve got a bunch of new followers… Hey y’all. My name is Mahaneela. I’m a multifaceted artist. I focus my energies on documenting people from the African and south Asian cultures, both communities that I come from,” she started.

Taking me off-guard, she bursts into laughter at the entire ordeal when it’s brought up in our chat.

“Before this started, maybe I had twenty-five thousand followers, or something? And now I’ve got forty thousand? My followers are just growing and growing as more guilty white people are brought my name,” she tells me, breaking into the same successful chuckle from before.

The part of the caption that intrigues me the most, though, comes at its very end: “I know many of you have been pointed to my page as a ‘black artist to follow’ and I truly hope you stick around and support my work when the time comes!”

I ask her if the support she wished for has been granted up to now. For the time being, merely a few months removed from it all, it’s difficult to tell for sure (“So far, so good!” is the consensus reached). But upon our bringing up of 2015’s original Black Lives Matter movement – and the way similar outcries to rally behind creatives of color were treated as a trend, squandered soon after – Mahaneela is quick to voice an outlook on support she’s carried before the fame, before the socials, before the prosperity: “Whether or not people know who I am, I’m always going to be consistent, doing what I’m doing,” she declares, poised and unfazed. “It’s going to be at some point undeniable, where my reputation and my work will precede me. So I don’t care about Instagram followers at all. Of course, it’s obvious that it does appease a lot of people’s guilt to say ‘Oh look, I’m following black photographers now, I’m doing my part.’ And unfortunately, that’s probably going to be the reality for a lot of people. But I’m just going to keep working, keep doing what I’m doing. No matter who’s watching me out of white guilt or not. As long as I’m getting paid – as long as I’m getting opportunities – I’m going to keep climbing on my journey.”

Before I leave her to return to the well-deserved Jamaican respite peeking through her camera frame, I am curious to know the origin of her name. She tells me it was made up by her grandfather, also someone deeply rooted in artistic endeavors. ‘Maha’ translates to great, and ‘Neela’ translates to blue.

She smiles when she glosses over the fact that she’s the only one in the world with her title. Without mentioning the book, she revisits a cornerstone of the Four Agreements (Agreement #4) in explaining what such a distinction has meant to her.

“There’s only one me. I can only do things in my way, you know? And that’s the best I can do. As long as I did the best I could do, I’m good.”

As we log off of the Zoom call, the afternoon sun glares through her screen with a vengeance. It’s about 3 PM in Negril. The weeks to come will be demanding for Mahaneela: on top of braving travel restrictions to return home to Brooklyn, upon doing so, she must once again fully immerse herself in the various artistic avenues she does her business in, sleepless nights and lengthy work days all factored in.

But for now, the sun is all that matters. It seems angry that I’ve taken her away from it for so long. I let her get back. And with complete certainty that, no matter what is endured in-between, the lifestyle she leads will find her beneath the same raging sun sooner than later, I click the button to end the call.