Kid A, much like the early internet era it emerged from, is indicative of a knee-jerk response we are prone to exhibit whenever a culture-shifting innovation dares to be confusing: there can only be either emphatic revulsion, or emphatic evangelism.

SAMUEL HYLAND

There’s an oft-resurfacing clip from a 1994 The Today Show episode that features three stumped NBC news anchors, mid-way through a segment entitled America the Violent, who grow suddenly puzzled at the crime beat’s new “Internet Address” ([email protected]). Confusion about the “Internet Address” wastes little time evolving into confusion about the Internet writ large. “What is internet, anyway?” one anchor, increasingly flustered, erratically demands. “How does one- Wha- What do you, write to it like mail?” It’s somewhat analogous to a segment in Radiohead’s post-OK Computer documentary “Meeting People is Easy” (1998), wherein a similar assemblage of news reporters quizzically seeks to understand how Thom Yorke is able to remain underwater throughout the music video for “No Surprises.” They all look stupid when, immediately after this scene, the documentary cuts to footage of Yorke’s head submerged for seconds at a time while extremely sped-up portions of of the single hammer away in the background. But the increasingly-clear line hindsight makes drawable across both scenarios is that news anchors look stupid whenever there is new technology — and, with such a standard being the metric, Radiohead’s OK Computer may well have been for rock music what the internet was for the world.

“For some Radiohead fans, it may have been a funereal confirmation for what had already sounded like the end of an era — Radiohead couldn’t be here for the outcasts anymore, because they had already graduated onto the other side of the wall.”

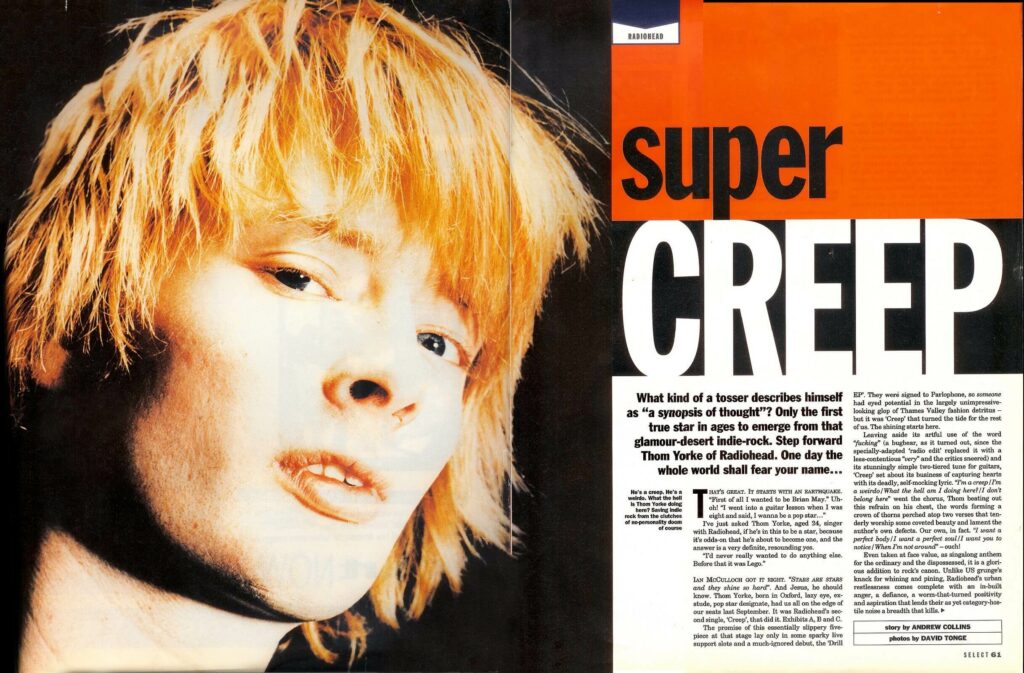

The appeal of OK Computer vested itself primarily in an existentially emo, loner’s-best-friend positionality that, though Radiohead would ultimately wind up rejecting it, ostensibly took the steering wheel for a majority of the group’s early ascent. “Creep,” the landmark single that likely had a larger following than the band itself at some point, was a wrenchingly sarcastic plea to societal ingroups that High Fidelity author Nick Hornby crowned a “voice to everyone who has ever felt disconnected, alienated, or geeky.” Contrast this ethos with the band’s OK Computer follow-up Kid A (2000), and there’s a dramatic tone shift on the part of artist and critic alike — a little bit further down in the exact same New Yorker piece, Hornby dubs the ensuing album “morbid proof” that “self-indulgence results in a weird kind of anonymity, rather than something distinctive and original.”

The “self-indulgence” in question had been a sentiment held not only by Hornby, but a notable sub-community of Radiohead listeners who, with this record, felt themselves subverted by the notion of a once-democratizing band now beginning to take themselves too seriously. The loudly anti-everything guitar of Jonny Greenwood, for instance — the most palpable vehicle, behind Yorke’s quivering wails, of “Creep”’s inclusive lonerism — finds itself all-but-entirely replaced in the record by ominous synths and muted piano keys. Speaking to Rolling Stone’s David Fricke for a cover story on Kid A, Greenwood, midway through taking Oxford University’s elitism to task, mused that “everything that is worth seeing, that is beautiful and traditional, is behind a very tall wall designed to keep the students in and to keep you out.” The complicating factor for many first-time consumers of Kid A was that Radiohead had seemingly graduated from one side of the wall, and, en route to indulging in whatever egotistical pleasures lay on the other end, left the devotees that had heaved them over it behind.

Pre Kid A-Radiohead was analogous to the internet beyond the realm of stupefied reporters, and more in line with a diversifying ethos, one the record drew flak for somewhat abandoning. As Radiohead were undergoing their own existential mid-career narrative arc, the internet was churning its way through a similar consumer-driven pivotal panic — freshly arisen from humble beginnings where it, much like Radiohead upon their earliest releases, was obscured to the extent that “internet” struck the same chord as “metaverse” does today, suddenly garnering global acceptance meant just as suddenly having to publicly make sense of it. Radiohead and the internet each wound up being embraced by the masses because they offered things the future wouldn’t be able to live without. When the liberty was extended beyond manufacturing an “app” (as Ye would put it) for an entire race, though, the task in both cases now became to somehow make a sequel to what was already an entirely new way of life. Following up OK Computer was like following up computers themselves.

The inherent pressure of such a task certainly wasn’t lost on its bearers. The aforementioned Rolling Stone cover story begins with the moment Yorke knew he had hit rock-bottom — gagging backstage at a concert in Birmingham, England, burnt out from OK Computer’s grueling tour to the point where he couldn’t formulate words to respond to the several people asking him whether he was okay. Yorke’s “tortured artist” appeal, exclusively cast onto him by the press and entirely disavowed by the man himself, was yet one more facet of their emo-bred ethos Radiohead sought to dismantle with Kid A, and at some level, it was dually indicative of the band’s own selling point writ large. People loved Radiohead because they were tortured, and, in being so, also the de facto megaphone for other tortured people. Radiohead’s sonic internet became a haven where torture was at the forefront — which was synchronously utopic and dystopic, in the sense that while the tortured finally had a voice, given that the voice of the tortured also happened to be tortured itself, the entire construct was a vicious cycle solely capable of producing more torture. A haunting manifestation of it in the “Meeting People is Easy” documentary comes when, upon exiting the set of the Late Night Show with David Letterman, Yorke is heckled by two strangers who, upon being turned away by security in a dimly-lit backstreet, target their verbal onslaught to the band instead. “Dude, write a song about it!” one pubescent voice yells. “Come on man, write it right now.” A horn blares, and there’s another boisterous voice echoing from across the street. “Radiohead! Creep! Dickhead!”

Kid A opens with the line “Yesterday I woke up sucking a lemon,” a reference to the sort of sour grimace both lemons, and nasty attitudes, tend to plaster on unsuspecting faces. “You can fall very easily into the mind-set of being the victim,” Yorke told Fricke, outlining the ways the OK Computer era plastered the look onto his own face. “It only takes a few times for you to give into things that you shouldn’t have. The easiest thing to do is resent it. And I was incredibly good at being the victim. You can abdicate responsibility, fuck things up whenever you choose and not have to explain yourself.” With Kid A, Yorke and Radiohead were tasked with creating a sequel for the very thing that had most victimized them, while simultaneously making it a point to not actually be the victim. This would mean rupturing the torturous cycle that OK Computer had thrown into overdrive, but given that the entire appeal of the band up to then had been this exact cycle, no matter how good the follow-up objectively was, Kid A was somewhat doomed to fall short of the consumer-driven bar that its predecessor set.

“Nobody was asking the internet not to grow, or change, or do something different, because, from its inception, growth, change, and difference were inherent to its lore — the ethos of the pre-Y2K internet was quite literally its impossibility to be understood.”

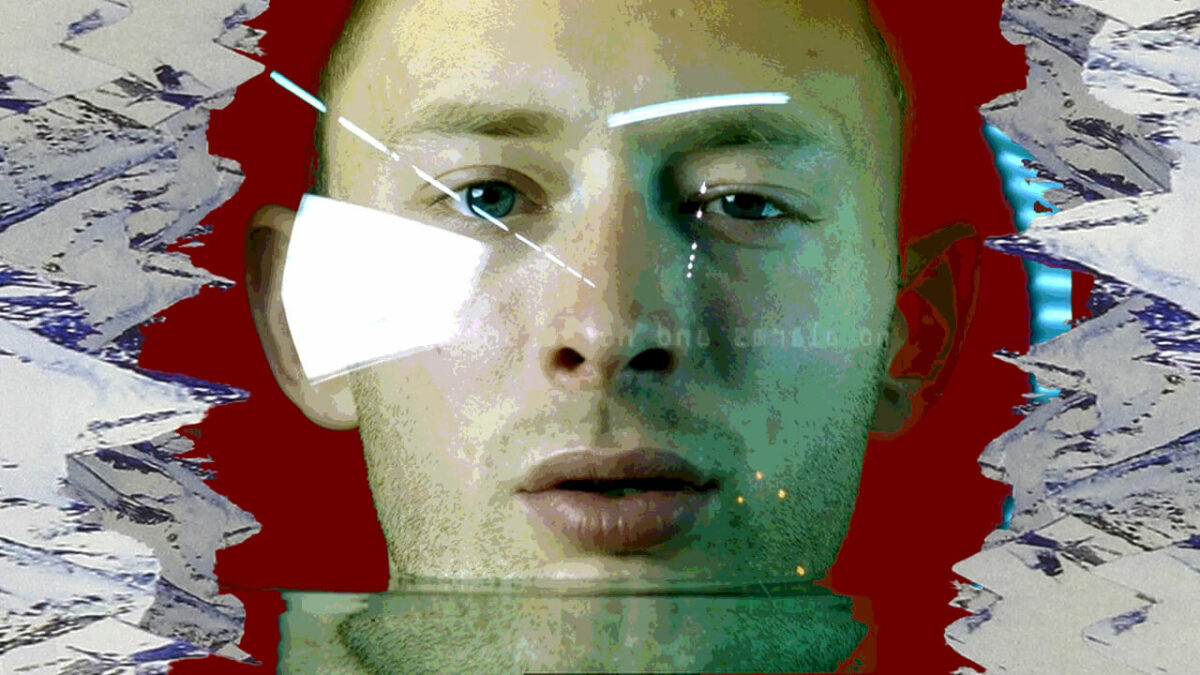

For Radiohead, growing out of OK Computer’s torture cycle meant growing up in general, and growing up in general meant taking themselves a bit more seriously — just as much of a perfect recipe for making mature music as it is for constructing a wall between it and everything else. Both musically and symbolically, Kid A registers a lot like the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ fabled Dave Navarro-assisted One Hot Minute, or Fleetwood Mac’s ill-received Rumours follow-up Tusk: packed to the brim with intriguing soundscapes, each profound in their own right, albeit alienating to audiences already in love with different ones. Whereas, for instance, OK Computer’s opening tracks were defined by the kinds of hyper-distorted Telecaster riffs and voice-cracking existential wails audiences had long come to expect from Radiohead, Kid A’s were markedly more solemn, boisterous string assemblages replaced by hymnal synths, and radical screeches substituted for by contemplative electronic voice filters. “How to Disappear Completely,” one of few tracks where Greenwood’s guitar appears at all (though acoustic and fairly muted), sounds like the kind of paean a contemporary Catholic church band from 2076 would perform at the funeral of its longtime organ player who killed himself because of disillusionment with the world’s secularization and an impending fear that his at-home robot servant is liked more by his wife than he is. “I’m not here,” Yorke croons, twice, at the ends of most of the song’s verses. For some Radiohead fans, it may have been a funereal confirmation for what had already sounded like the end of an era — Radiohead couldn’t be here for the outcasts anymore, because they had already graduated onto the other side of the wall.

Concluding his scathing New Yorker review, Hornby suggested that the band ought to tap further into the sonic ethos that had made them famous in the first place. “Nobody is asking Radiohead not to grow, or change, or do something different,” he wrote. “It would be nice, however, if the band’s members recognized that the enormous, occasionally breathtaking gifts they have—for songwriting, and singing, and playing, and connecting, and inspiring—are really nothing to be ashamed of.” With Radiohead’s rise (and fall?) being analogous to that of the internet, it becomes necessary to consider what this question looked like for its technological counterpart as well. Nobody was asking the internet not to grow, or change, or do something different, because, from its inception, growth, change, and difference were inherent to its lore — the ethos of the pre-Y2K internet was quite literally its impossibility to be understood. Radiohead differed in that some devotees wanted to understand them, and some were just as content with being surprised by their artistic choices. So when the group, which had established itself as music’s new internet with OK Computer, elected to abandon all that had made them just that, the playing-field was evened in that there was no more sensible line across which fans could even be split anymore — just growth, change, difference, and paranormal synthesizers to be reckoned with.

When, upon being asked about it by lucky kids who had won the chance to interview them on the radio, Thom Yorke was made to address the band’s departure from the sounds of OK Computer and sophomore LP The Bends, his response was as pointed as it was polite: “That’s like saying to a painter, ‘Can you just paint that again?’”

📡 📡 📡

A little over eight months before Radiohead released Kid A, the world was working itself up over the prospect of Y2K (Year 2000 [Problem]), the fabled all-around digital apocalypse that would predictably be spurred by computers’ inability to process the turn of the century. Much like Radiohead’s post-OK Computer music, the era, though entirely sloppy and dystopic as it was happening, has evolved to become a fetishized object of 21st Century cultural necromancy, haunting the crevices of themed playlists, dorm room parties, and pre-teen closets via the allure of being fluent in things that once were points of existential confusion.

With Y2K marking a new digital internet the way Kid A marked a new sonic one, it becomes ostensible that whenever something bisects time like they both did, widespread understanding of it can perhaps only become possible decades in hindsight. It isn’t cool to be in tune with something collectively confusing (ex: the “metaverse”) while it’s making its first run, but when the hype has simmered and the confusing thing has found a cultural crevice to nest in, the ability to reflect on it with clarity is valued by the culture, because it tells it that it won. Y2K parties are such a fixation twenty-two years later, because they signify a level of control over something we once thought was going to kill us. Just the same, finding ourselves able to enjoy an album our parents reviled as teenagers registers as a larger generational victory, one that makes us both aggressively cling to, and vouch for, the music so long as it continues to affirm our sense of control over what used to be uncontrollable.

The thing with both Y2K and Kid A, though, is that as much as they each fell victim to the late appreciation inherent to temporal unknowns, they also carried with them a certain vitality that forced consumers to at least try to make it all make sense. The internet had already established itself as integral to the future of human life, the same way that OK Computer had already established Radiohead as integral to the future of rock music. Much unlike the oddities of different eras, the entire internet could not be dismissed as a fluke, nor could Radiohead. The futures of both humanity and rock music were contingent upon consumers being able to pretend they understood what they didn’t. And, although some critics like Hornby were quite transparent about the fact that they had missed the memo, a large demographic of writers and fans alike were content with praising it in ostensible hopes to force the future into being palatable.

“Kid A is no Metal Machine Music, and Y2K was no countercultural revolution, but as of today, both live on as signifiers of a culture that loves faux futurism more than it does grappling with complex realities.”

Pitchfork’s review, a perfect-score appraisal still mocked online for its headass over-the-top geekiness decades later, was one of several stark instances of an apparent stretch to feign not only understanding of, but intrapersonal connection with the uncertain future the LP signified. “The butterscotch lamps along the walls of the tight city square bled upward into the cobalt sky, which seemed as strikingly artificial and perfect as a wizard’s cap,” Brent DiCrescenzo wrote. “The staccato piano chords ascended repeatedly. ‘Black eyed angels swam at me,’ Yorke sang like his dying words. ‘There was nothing to fear, nothing to hide.’ The trained critical part of me marked the similarity to Coltrane’s ‘Ole.’ The human part of me wept in awe.”

Critical and commercial response to Kid A, along with the new internet era it emerged from, are indicative of a knee-jerk response modern civilizations are prone to exhibit whenever there is a culture-shifting innovation to be contended with: there can only be either emphatic revulsion, or emphatic evangelism. It’s a dynamic wasting little time translating itself into our transitional era, whether musically, with copypasta-toting haters waging vigilant wars with (insert artist here) profile picture stans whenever a controversial new album challenges cultural status quos, or digitally, with valiant Web3 evangelicals eternally fighting to vindicate their beloved NFTs while the other side of the internet eternally fights to keep the threat a laughing matter.

With the perfect mixture of context and content, Kid A was polarizing enough to be the kind of cultural object that, in this same vein, bisected time and response alike. “What they have done seems to be very clear and smart,” R.E.M lead singer Michael Stipe (then an avowed Radiohead fan) told Fricke. “Which is, with the number of hits they’ve had, they are simply staking their claim as their own band, making music they want to make — no one’s lapdogs, whether it’s an audience, a record company or their peers.”

A similarly-polarizing record remembered by history, one that Hornby went as far as to cite in his New Yorker critique, is Lou Reed’s feedback-driven 1975 opus-slash-downfall Metal Machine Music. Even by today’s far-evolved sonic standards, the album is barely digestible, if even digestible at all — four lyricless songs (except for, of course, what may or may not be primal screams blending in with the ones belching from the overdriven titular “Metal Machine”) spanning at about 15 minutes each, serve as experiments in how much the mind can tolerate, the noises just as ear-splitting and loud as they are monotonous. (“If there was justice in the world,” Hornby wrote, “the record would have resulted in a large fine and possibly even a short prison sentence for its creator.”) Still, yet, much like it did for the then-small subgroup of devotees that granted it a cult following because they were unable to make sense of things without Reed in 1975, the primal desire to understand the future continues to outweigh the possibility that the music is simply bad. The sentiment goes from amateur Amazon.com reviews for the vinyl reissue — “Assuming that you can appreciate EXTREME drone music (which most people couldn’t back in 1975), this is a rather beautiful and bracing listening experience,” one customer wrote in a 4-star review — to professional Pitchfork revisitations: “Lou Reed’s 1975 album has been called one of the worst albums ever made,” Mark Richardson wrote. “The truth is it is the product of genuine love and passion, still exhilarating and bursting with possibility four decades on.” (The album earned a rating of 8.7 out of 10).

Kid A is no Metal Machine Music, and Y2K was no countercultural revolution, but as of today, both live on as signifiers of a culture that loves faux futurism more than it does grappling with complex realities. And, as much as such a construct sounds terrible on paper, it’s a vicious cycle that can never realistically be broken out of — we like feeling like we have a grip on things, because not having a grip on things means we just might not make it. So, instead of coming face to face with the fact that we actually can’t wrap our heads around something, we’re typically much quicker to dub it either a work of genius or a fluke before opening up to the potential that we simply do not understand it (yet).

Y2K prophesied a point where the internet would, much like Radiohead post-OK Computer, begin to think more for itself than for the people it was manufactured to serve. This is a much more terrifying prospect in the realm of computers than it is in the realm of rock music. Depending on who you ask, that day may have already come — the Web3 revolution many dread is contingent upon making the internet a self-serving being run entirely on the horrors of digital-era capitalism — but even if you don’t believe that such a horror may ever arrive, that does nothing to erase the possibility. If Y2K and Kid A are proof of anything, it’s that we are under constant existential threat. We can spend as much time as we want building up monumental boons, whether they be digital communications systems or lonerism-preaching emo rock bands. But at some point, the possibility exists that we will talk to them, and they will not talk back to us. All we’ll be able to do then is pretend it makes sense.