An epic conversation with an equally epic multi-disciplinary artist about pessimism, self-immolation, and removing oneself from the rat race.

SAMUEL HYLAND

A great deal of the culturally appreciated homebound-mad-scientist artmaker persona can be attributed to Hugh Hefner, Playboy’s now-deceased eccentric mastermind. Hefner, as reported by Tom Wolfe in his essay King of the Status Dropouts, owned millions of dollars’ worth of lavish property ranging from Las Vegas to Manhattan: he dropped 2.3 million on a leasehold to convert the Chicago downtown’s Loyola building to his own company’s headquarters without ever seeing it in real life; He built scores upon scores of Playboy clubs boasting over 600,000 eagerly-paying members across six continents; he had rights to an upscale condo in New York’s garment district that he seldom saw with his own two eyes. But the thing about Hefner was, that even with all of this to his name – in perhaps the most impressive element of his construct – he never left his own house. Day after day, the bathrobe-clad businessman knelt on all fours in a rotating, larger-than-life, remote-control bed, madly lathering in his own cult-of-personality, waking up whenever he felt like working on the Playboy Philosophy, and being tended to by scantily-clad Playmates who happily satisfied both his culinary and sexual appetites. This was the office for Hefner. There were no desks, no strict suit-and-tie dress codes, no corporate linguistics. When Hefner realized that he could function just as effectively as anyone else without leaving his bed, he did just that: he subtracted the elitist manifesto. Then he brought the office to him.

When I arrive at the top floor of Louis Osmosis’ Brooklyn apartment-slash-studio, the multi-disciplinary artist stops to call something out in Chinese to his young cousins, Matthew (10) and Fei-Fei (9), who have been loudly playing in a room downstairs. Mere seconds after they are summoned, the two march with military-esque uniformity into a wooden door marked OFFICE, each bearing chewed gum in their outstretched palms. Matthew and Fei-Fei emigrated to the U.S from Hong Kong with their uncle in December of 2019, following an intensification of local protests. “What had happened was that they were living in, like, the equivalent of a housing complex – it’s not like America where the shit is like, fucked; over there they actually had amenities,” Louis explains. Soon, demonstrations grew increasingly violent whilst moving increasingly close to home – and with unrest only growing stronger, the family quickly opted to leave their homeland permanently. “They were just like hell to the fucking no.”

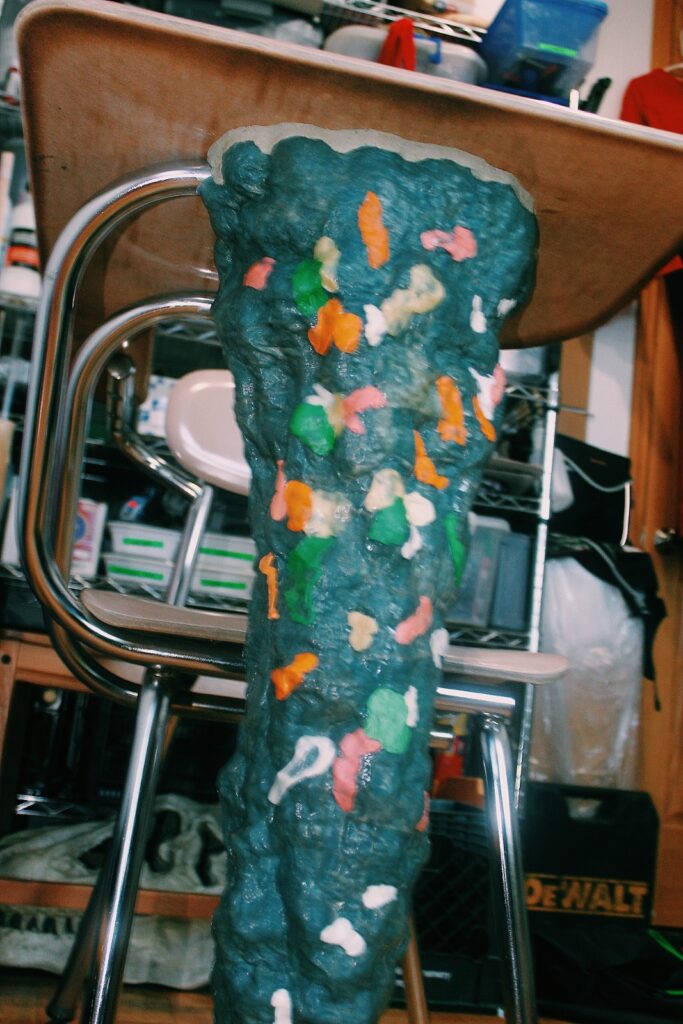

As I observe from a couch today, though, the siblings emerge from the OFFICE door with the same single-file uniformity in which they entered. There is no longer gum in their palms. Louis invites me inside, casually beckoning towards a jarring artistic monument to my left: it’s a typical school desk, the type you’d find covered in pencil drawings at the back of a squalid inner-city high school classroom. Yet – stuck to the surface underneath it – there is a gaping, cone shaped, nearly-terrifying monstrosity of sculpted material with about thirty pieces of chewing gum plastered across its front. In strategically giving his cousins an excess of gum, along with chewing a similar amount himself, he tells me that he hopes to have the entire thing completely covered in about two months. Already, it appears as if the desk has been stationed in the same detention room since 700 B.C.

This wouldn’t be Louis Osmosis’ first time extracting art from the depths of classroom desks. Born Louis Chan, the 24-year-old lifelong New York native first coined his current moniker over a fateful series of days in middle school. “We were learning about mitosis, meiosis, blah blah blah. Then a couple weeks later, we landed on osmosis, and I was like, that’s such a fucking pretty word. And I remember she put up this diagram on the board; it had to be drawn on some science blogspot thing because it was done with Microsoft Paint, and it had the Times New Roman captions – it looks like something Virgil Abloh would have on, like, a moodboard now, but never be able to replicate,” he recalls of his biology class with a sarcastic smirk. “And then the week I was learning about osmosis, I was watching one of my favorite shows in my childhood, that I was fucking raised on: Iron Chef America. It was an episode where Masaharu Morimoto uses a Sous Vide machine. Alton Brown, the guy from Good Eats, he pulled out a blackboard – and on it was the word ‘osmosis.’ I was like this is a fucking sign.”

“I can look at something, realize the end, and have the end be a point from which I can enter.”

Prior to the name-switch (which, at that point, was only a matter of a Facebook status update), Louis attended Mark Twain Middle School, an arts-oriented gifted-and-talented institution in Brooklyn. Going into ninth grade, although his mother desperately wanted him to attend the elite Stuyvesant High School, he intentionally left a considerable portion of the SHSAT (Specialized High Schools Admissions Test) blank in order to attend his preference, Manhattan’s Laguardia High School for Music and Art & Performing Arts – where he met longtime friends Jasper Marsalis and Timothée Chalamet (the latter of which was the subject of about ten of Louis’ Instagram DMs today — most were awestruck teens offering him big bucks to reach out to Chalamet for them).

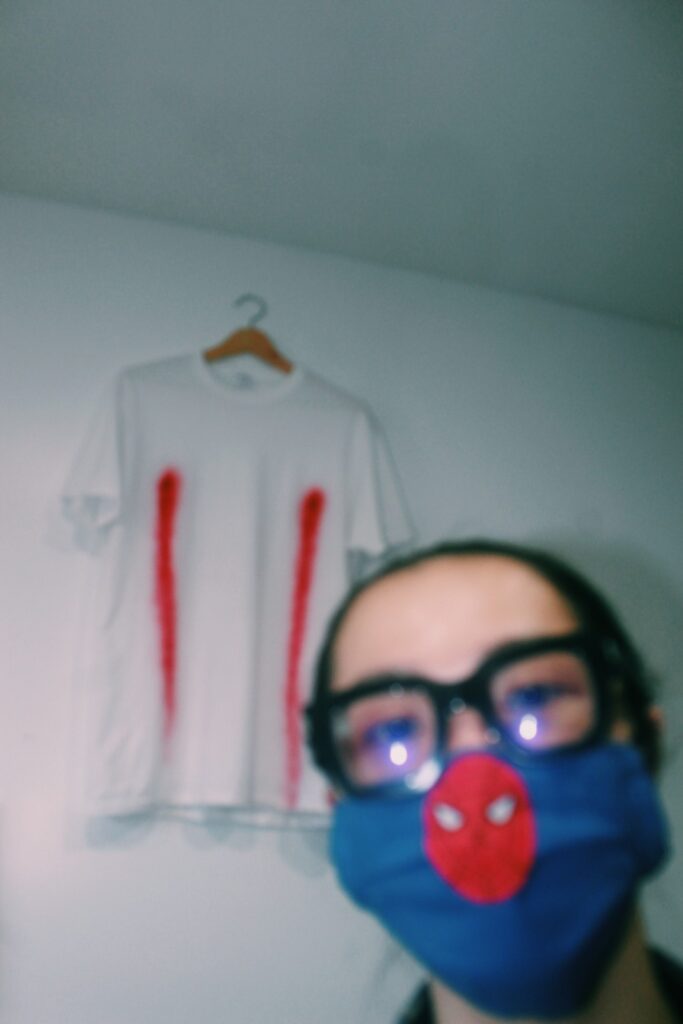

Walking about in Louis’ studio is like a hyper-exaggerated trek through the upside-down connotation of Hefner’s spin on an “office.” Much like it would for anything not bearing a desktop and a few rolling chairs, the word OFFICE printed across the wooden door reads as a sarcastic gesture, seldom preparing the first-time visitor for what’s inside: there is a faux-bloodied T-shirt hanging up somewhere as part of a you-get-it-or-you-don’t series Osmosis plans to do on nipple chafing; there is a humanely-sourced red footed tortoise shell with remote-control car antennas protruding from each hexagonal scute; near the back there is a lofty paper-mache car engine sculpture – just a bit taller than me – positioned right next to a thoroughly deconstructed car seat Louis plans to utilize at some point in the near future; there is a section of a wall dominated by various construction tools; the first thing one may spot upon entrance is a Chinese newspaper clipping in which the only words not written in Chinese are English profanities.

Louis’ unapologetic tendency to resource found objects and nature alike – two examples being a series of drawings he did by imposing the sun’s magnified reflection on wood, and an organic sculpture intentionally left out in the elements for a while that he’s still strategically seeking to get a bird (preferably a seagull or a pigeon) to excrete upon before he calls it finished – has garnered him a low-key, but authentically eclectic presence in Brooklyn’s art scene since he graduated from the Cooper Union in 2018. Around this time last year, he put on a show entitled This Is Your Captain Speaking in tandem with his close friend Thomas Blair; it was described by the Brooklyn Rail as what one would likely see “if Pornhub had an art-for-pay section.” At this very moment too, he tells me, he has several pieces en route to Los Angeles for an upcoming show he’s being featured in, and sometime before or after it, he is planning to produce his first solo exhibition in New York City. “I’m someone who really, overly, cares about how I’m perceived,” he says, sitting with me in his studio. We’re getting into what a certain exhibition of his did for him mentally, and the conflict of being thought of a certain way versus being perceived a certain way has been brought up. Louis is adamant about the sort of perception he is working towards. “Something as small as oh, you made this work? I didn’t know that. You don’t look like you could make this work. But now that I see you, it kind of makes sense. Shit like that. A lot of times when you go to an art opening, you can pick out the artist (snaps) like that. Which is not a bad thing, not a bad thing at all. But that’s something I would like to play with, and fuck with.”

Louis Osmosis wishes he lived in the 70s – not “on some I-was-born-in-the-wrong-generation shit,” but because smoking was more generally allowed in facilities across the country then. As we begin our interview near a deep, cluttered outdoor garage in which he stores tools for future projects, there are no anti-smoking regulations to hold him back: he’s puffing away at a bogey with one hand, fiddling inside the pocket of his North Face coat with the other, and standing with the kind of Hugh Hefner-esque swag of knowing that he doesn’t have to force himself into the rat race if he doesn’t want to. The first question – one he poses to himself – is a rhetorical one. I start off by asking him to answer it.

In Conversation with Louis Osmosis

SAMUEL HYLAND: The first question I want to ask you is-

LOUIS OSMOSIS: (Laughs) Where do you get the nerve?

You know what, yeah. Say that. Where do you get the nerve?

I’m just hot and bothered. I think that’s the most straightforward, non-pedantic answer I can give.

Hot and bothered.

Yeah. I think everyone is.

What are you bothered by the most?

There’s this writer who passed away recently, by the name of Mark Fisher. He wrote a book called Ghosts of My Life: On Hauntology and Depression. You know how with some books, they would have a quote before they start? His quote was: ‘Lately I been feeling like Guy Pearce in Memento’ – Drake. That book damn near changed my life, in a very non-art theory way; it took me a while to understand art theory. That book is super accessible. It’s a challenging read, but definitely super accessible – and it’s the first time I felt woefully affirmed about my feelings about cultural production at-large. The biggest takeaway from that book, or the quickest takeaway, is a quote where he says: “nobody’s bored, everything is boring.” That’s where I get the nerve. Everything’s boring, so let me do everything I can to not participate in that. I feel like to resist the hegemonic structure is an exercise in futility unless you’ve got the money to back it up, or the power to back it up. But an exercise in futility is not a futile exercise. It’s a very interesting and fruitful thing to toy with that. And that’s where I get the nerve.

I would argue that everything is brainwashing to a level. Everything is designed to make you participate in this thing you were talking about, the idea of success and chasing after it.

Yeah. It’s like this attack-from-all-angles sort of situation, arising from the conditions that we currently live in. I go back to the tortoise shell piece. That piece has these, what I call “Chrome Vectors,” coming at you from all angles, pointing from every which way. Except from the underside of the shell, where the tortoise would be. There’s this kind of arrested development that happens; it’s kind of like a violent gesture a little bit, to take a turtle – which is meant for the ground – and then put it on the wall as, like, a taxidermy mount.

Right. You look at it, and it feels violent. Like, it invites you to look at it, and then it throws everything right back in your face.

Exactly.

How was your Christmas, though?

It was good, I was with family; I was with kids. I got all my family members – at least the ones who wanted more than just money – a genuine gift. You know, Chinese people just give out money. They don’t put too much thought into gifts like that.

People at schools I’ve been to have been really generous with it. A dude came to school one time with seven hundred dollars in his pocket, and he was claiming that he had a thousand more at home.

(Laughs) Jeez, that’s OD. That’s crazy. But yeah, I made my mother a portrait of me and her, like a drawing. And then I sewed like a heart-shaped pillow out of this fabric that’s on my knee for my cousin; she’s like the closest thing I have to a sister – I’m an only child. And then I got my aunt a watering can, with one of my old ceramic pieces from Cooper (Union). Then I got the kids Minecraft keychains.

Swag.

Yeah, ‘cause they’re big on Minecraft.

I could never get into it.

I played it when I was like a kid kid, but Minecraft now is a very different thing. It’s way too advanced for me. But that was the first time I gave out OD Christmas gifts – like objects. It just felt right, you know? Everybody was in this slump, my mother’s been going through it this year; you know, everybody in the world is going through it right now.

You were talking about this slump a lot when we were inside, too. What was that period like for you, like when you couldn’t find this artistic thing you wanted to tap in with?

Well the slump . . . I guess it was this sort of internal reckoning that I only realized was that in hindsight. Just everything – capital E everything – feeling like it was happening at the same time. But at the same time, this was like the planets aligning in order for something else to be possible. It was an internal reckoning with that. Mentally trying to juggle everything that was happening. I mean, on top of that, you had the more immediate personal parts of it, which is like – you know – jobless; trying to be an artist, which offers no security unless you sell your soul . . . it was a lot. I’m someone who, in my junior year of college, was violently depressed. And that’s something I will always carry with me. I got out of it, but that shit never leaves you. I don’t want to romanticize this whole thing where it’s like ‘sadness is the foundation for production to happen.’

Yeah, this idea of the “tortured artist.”

It’s super corny. But I think what’s more applicable is that it garnered in me this sort of pessimistic outlook on life. Not in a way that’s self-defeating or nihilist, but in a way that is productive. Like, I can look at something pessimistically and not just come to an end, like oh, what’s the point? I can look at something, realize the end, and have the end be a point from which I can enter.

You said something in your Brooklyn Rail feature about having tapped into a genuine thing in your art that you couldn’t exactly make sense of. Walk me through that.

Well, I think it’s like that pessimism shit I was talking about. A lot of my time at Cooper was this hellbent endeavor towards success, and readability, and legibility – and again, I always felt dissatisfied, but I never admitted it. I was too scared to do something about it. Then post-Cooper, with the prospect of an immediate art community kind of gone – because, like, I had my friends and shit, but to be in a room full of people, including people that you don’t like, and strangers, people whose work you admire: to have them talk about your work? That’s a fucking privilege. Because you never get that shit after, unless you go back to school or you organize some shit, which is hard as hell to do. And you need people you don’t like to get that perspective too, because now you have something to offer.

That’s something I love and hate about music reviews. I love it when editors get people who lean more against the artist – whether intentionally or not – to review their work; like, they got a consistent Cudi critic to review Man on the Moon 3. And people were hating in the comments, but that was because they were Kid Cudi fans. It’s that dynamic of consuming from outside of the box instead of being like “I support you unconditionally, so everything you do is good.”

Yeah. That kind of tactile genuinity I feel that I’ve tapped into is fully this sense of – I’ve said pessimism, but . . . hold on, lemme grab my sketchbook. (Louis grabs his sketchbook, and flips it open to a specific page). Lauren Berlant. To use her coinage, I feel like I’ve tapped into, like, a “cruel optimism.” That phrase has resonated with me OD. The quintessential understanding of pessimism is that it’s borderline nihilism, but at the core of pessimism is its teleos. Meaning that it’s based on an end; it’s based on reaching a conclusion. It has a conclusive nature to it, that I resist. I think pessimism can still maintain room for an approach towards it that isn’t inherently attached to some idea of reaching a conclusion – if anything, I think it’s this idea of suspending ends. For example, there was this article I read when the Ferguson protests were happening . . .

Like 2017-ish.

Yeah. I can’t remember who wrote it, but the title was something along the lines of “Violence and Pedagogy.” The person who wrote the article was talking about this video they’d seen of these protesters a couple of feet away from this police brigade, with their riot shields and everything. He notes that in the video, they’re not just stampeding towards them – because they know they’re outnumbered and outgunned. So the protestors are kind of scattered. And they’re sort of marching what looks to be aimlessly; they’re all kind of circling around their own personal space. Collectively, but still respectively individualized in their space.

It’s like that thing in Chemistry, entropy.

Yeah, for sure right? Exactly. And then he notes that in the video, they’re throwing things at the police brigade. You can tell they’re not throwing to break down the squad; they’re not throwing projectiles to destroy the police brigade. Because they know they can’t. What they’re doing, rather, he posits, is that they’re testing – they’re sort of prodding at this horizon they’re being confronted with, the horizon being the police brigade. It’s like the dividing line between ground and sky, the horizon. And they’re throwing objects at it to prod the extent of their reach. Rather than trying to break it up in a very linear way, it’s more of this thing of testing their limits. Their visual reach, but also, one can argue, their political reach. Now you go to protests in Hong Kong, and that’s fucking art-bait, through and through. And I’ve had to check myself a couple times to not just make a facsimile of the formal poetics that are happening with these protestors. You know? Motherfuckers are using laser pointers, like, making light shows, in Hong Kong to obscure their CCTV feeds. You have a fucking protester who’s unlawfully arrested based on the fact that the police had said that the laser pointer was an incendiary device – like it could light a fire. And this is a lead organizer for the protest. What a bunch of protesters did en masse as a reaction, was they went to this observatory in Hong Kong; the outside of it is made with this sort of paper skin material. And they just started making a light show on it, as a sort of petty thing, as if to say look, it’s not an incendiary device. And it’s fucking beautiful. That approach is all about illegibility. It’s unsuccessful – or not unsuccessful, rather I should say non-successful. It is deprived of this aspiration towards success.

So being unsuccessful would be striving for something and failing, whereas being non-successful would be completely being removed from the aspirational element.

Exactly. There’s no care for success. It’s not a type of protest where they’re like “Here are our beliefs. Here is where we stand. Please pay attention to us. And please let us ameliorate together.” No. They know that that’s a project in failure – like, bad type of failure. What they’re going for instead is this extremely non-linear means of going about it. Which is fucking beautiful, you know? Like fuck. Fuck! Shout outs Hong Kong.

I want to ask specifically about Hong Kong – this is a through-line to a lot of the stuff you’ve been saying today, like how there’s a difference between being non-successful and unsuccessful, the same way there’s a difference between failing and not giving a fuck about succeeding in the first place. When you saw these Hong Kong protests, was it something that you looked at and instantly made that correlation to your art?

One hundred percent. One hundred percent.

Go into that.

It was one of the first viscerally literalized images of what I’ve been trying to get at in my work. But it wasn’t literalized in art: it was literalized in life. I literally cried about that shit one time in bed, just to myself. Because it was such a fucking ingenious approach. And that’s the type of poetics that hits like a truck.

Yeah, I feel that.

That correlation – immediate isn’t even the fucking word. It was like a fucking punch to my gut. Something I find myself obsessed with is the concept of an aesthetic excess. A metaphoric excess. That’s something I take from a Vietnamese scholar by the name of Sianne Ngai – she talks in an essay about this novel, that’s like this story about a street performer in Harlem who’s making a black marionette figure dance; and the crowd is going crazy or whatever. And then the protagonist of this story, he walks in and he sees the performance. And he’s disgusted. The way it’s described, it kind of echoes the way that if one were to see minstrelsy today; to see that shit, one would be disgusted.

Wait, what is that? Minstrelsy.

Like tap dancing, shoe-shining, that shit. And he’s disgusted. His disgust is displaced, because disgust is something like, you feel it and that’s it. This wasn’t that. It wasn’t your simple humdrum brand of disgust; it was displaced. Why? Because she posits this sort of puppet – the racialized puppet, mind you – in its stylization, like how it being a puppet determines how it occupies the world. It’s like a marionette, so it has a jittery kind of movement; and that initial disgust is displaced by that sort of wildly bodily movement. That produces an excess. There’s an excess afforded to the puppet and the puppeteer, where for the success of the person puppeteering the marionette, that box has been checked. But to check that box means to overdo it. Because it’s a puppet. It’s like how in Broadway or theater, they say you have to act to the back of the crowd, and not to just the front. That’s why Broadway actors do the most, you know? So to do the thing – even barely – you have to produce an excess. What’s happening in Hong Kong is all about that. And it’s the type of excess that’s one of the pillars I feel like I’m trying to get at in my work. It doesn’t symbolize or represent a sort of guttural feeling; it produces that in the viewer. Whether that be bodily, or in their head top, in their fucking mind.

What was the first piece you worked on after you got that gut-punch feeling?

I don’t know if I made a piece immediately, because that was something I was trying to avoid – like at the end of the day, I’m not. . .

A political artist?

Well, I wouldn’t say that. I don’t think that’s possible, actually; even if you’re a dipshit, you’re making political work. This might sound a little romantic to say, but think that to make stuff is political in itself. I was trying to avoid making a piece in response to the Hong Kong protests, because one, I was just not really interested in doing it, and then two, I don’t have any stakes in that. Yeah for sure I have mad family in Hong Kong; I’m like, a Chinese person; I’ve gone there almost every summer up until I was thirteen or fourteen or whatever. But I’m not a Hong Kong person. That’s not my fight. I support them like crazy. But that’s not my fight. I’m never going to have to deal with what’s impending for them.

That’s really mature of you, to pick your battles like that.

Yeah, you just gotta know your place.

Like it’s one thing to speak for a demographic, and then it’s another thing to speak with them. Like if you’re not in that area with them, then speak with them. But don’t speak for them, because then you’re overstepping your boundaries.

Especially me, because like if I said that shit here – “Shout out to all my Hong Kong people” – that would be OD out of pocket for me to say, because one, I’m not a Hong Konger, or person. But also, if I were to say that here, no one would bat a fucking eye. Which is strange; which is problematic.

About the genuinity you were talking about earlier, do you feel like you’ve been able to expand on that since the inspiration first hit you?

Yeah. I was gonna say I-D-K, but I would say yeah. Because I still feel challenged by my work. And I’m someone that likes to challenge people – and I’m definitely not safe from my own challenging of other people; I challenge myself to a point where it can be counterintuitive – but being counterintuitive goes in line with the failure thing. It’s fruitful for me.

You grew up here in New York. Walk me through how you found yourself in this artistic infrastructure you’re in now.

Are your parents from here?

No.

Okay, so you can fully relate. And this is not to say all immigrant parents are like this, but it’s to kind of say all immigrant parents are like this: They could give a fuck about me doing art. Or anything that isn’t a nine-to-five. My mother is the quintessential Chinese tiger mom. When I applied for high school, I also had to take the specialized high school test, the SHSAT – and I purposely left a lot of the math section blank, because my mother made me put Stuyvesant as my first choice. She wanted me to go there. And I was like there’s no way in fucking hell, you know what I mean? Like I’m gonna be a crust punk before I go to fucking Stuyvesant, like get the fuck out of here bro. So I purposely lowered my score so I could get into Laguardia, because I already got in with the audition.

You knew the math content though, right?

Yeah, not to gas myself up, but I fully would have passed. So that’s the sort of baggage. I love my mother; my dad is like a fake deadbeat. He’s like a ghost that’s here, kind of like Moaning Myrtle, you know what I’m saying? Like you see him, but he don’t really be doing nothing. He’ll help me out with a few construction things, but otherwise . . . yeah. My mother is more of my rock. I’m an only child, so having that, I’m super grateful for. But it’s really difficult, to this day still, to have your mother not support what it is that you do. She only supports it when she sees a financial return. Which I understand – she came here from fucking China, to Hong Kong, to here; had to get a bag. Had to. So I get it. I respect it. I used to try and change her mind on that shit when I was younger, but there’s no fucking point. She put me in mad after-school programs, like the regular-degular Chinese shit of like, Kumon and stuff. All of that, I did all of that. But I also had this neighborhood art teacher from when I was six or seven, up to when I was like ten, named Ms. Wong – which was heavy drawing and shit; it was mad foundational. And then I went to Mark Twain for art, then I went to Laguardia for art, then I went to Cooper for art. I’ve been going through the art school system, you know what I’m saying?

Do you still feel like it would have been more difficult, had you gone to Stuy? Like you’d currently be an artist either way?

If I’m gonna be brutally honest, yo, I think I might have killed myself, had I gone to Stuy. Like I really did not- can’t picture myself there, you know? I just knew what time it was over there, and I could kind of project what time it was gonna be had I gone there. To be brutally honest, I think I would have just killed myself, honestly. I have no problems saying that. This sounds morbid, and I think it sounding morbid is something that needs to be recalibrated – but I’ve been looking for scholarly texts, or just literary work about suicide, that isn’t either moralizing it or talking about it as a statistical feat. This sounds so pretentious, but I want to talk about it ontologically. As a position that one determines for oneself. Even if you don’t do it, or you do do it, if at some point you feel that viscerally, that’s the position that you’re in. Period.

Is that sort of the thinking behind the self-immolation sculpture you did?

Which one, the wooden figure?

Yeah, the one based on the protester burning himself.

Yeah, I mean when I found out about that story – the wood for that sculpture was from another sculpture done of Jan Palach, a demonstrator who self-immolated. And when I found out that that sculpture was in memoriam, too? I was like wow. Like, that’s . . . wild. And it’s wild that it failed. It failed. That approach failed. That protester’s approach failed.

There’s another story of a Buddhist monk-

Yeah, that really famous LIFE Magazine picture, right?

Yeah, the Rage Against the Machine thing.

Yeah. That shit fails, but its effect echoes through time. Because one, the poetics are just that crazy, like the visual: you see a pretzel-style sitting figure on fucking fire.

And that’s excess. That does more than it’s supposed to do.

Boom. Bing bong boom. Right? And then on top of that, I would argue that it’s able to have its effect linger through time, and echo and haunt throughout time, because it’s contingent on it failing. On that one person or group of people not being able to actualize the project that they embarked upon. Whatever political endeavor that may be, you know? Again, it’s the exercise in futility that produces the effect; capital E effect.

I feel like what makes this kind of imagery so groundbreaking is that you’re presented with someone who believes in something to that extreme extent – like they’re willing to fail for the sake of having half a chance at-

They’re willing to kill themselves! That’s the most spectacular failure, you know what I’m saying?

Defiant.

It’s super defiant. And then again, not to romanticize it, because of course I don’t want to do that – but it’s a spectacle of failure, because in a very pessimistic way, to live and to survive is to make yourself available to be mined for your potentiality. To live is to make yourself available. Period. To remove yourself from the equation . . . that’s fucking nuts! You know?

What is it, if anything, that you believe so much in that you would sacrifice everything for half a chance at seeing it actualized?

Mmm . . . I mean, on a very immediate rainbows and flowers means of address towards that question – like shit, if a motherfucker could end like poverty, that’d be fucking fantastic. But also, I don’t think there is anything I’d give up this shit for, just like that. Because I don’t think there’s anything that’s possible- just to logically entertain that prospect. As Mark Fisher puts it – he was asked to define capitalist realism, a phrase that he coined at a lecture somewhere – capitalist realism is one of those things that doesn’t have a definition, but when you see it, you fucking know it. One of his driving examples for what it is is that anybody and everybody can imagine a post-apocalyptic world way before they can imagine a world without capitalism.

Damn. That’s true.

And even in scenes, or images, of apocalypse or post-apocalypse, nine times out of ten, capitalism still seems to rise out of it. Whether it be through barter systems, or like, debt. It maintains itself. Which is fucked.

How did you find yourself in all of the disciplines you currently work in? Was it all at the same time? Or was it more like as you’re going to these art schools, you pick up drawing in Kindergarten, then you go on to sculpture in college, and stuff like that?

The way that I think about it, I honestly don’t really see them as that different from each other. Literally, in my head, I’d be walking around, see something cool, and be like that’s a sculpture. If it hits, I’ll just call it a sculpture.

Like Duchamp with the Fountain.

Yeah. 20 Min, by Lil Uzi Vert. That’s a sculpture.

So it’s like an audible sculpture?

No, I just know it’s a sculpture. Because it’s a song; a song is an object. It’s not in space, but that song does things for me – it produces a lot for me. And I can get into it in like, a social context. But the aural, the sonic attributes of it that I think point to a larger system at work – a larger trend at work – 20 Min does that. So in my mind, it’s a sculpture.

What do you define as a sculpture?

(Long pause) An object that does something.

I like that. So humans are sculptures, but only if they’re doing something?

Well, no, because I don’t want to go into the thing where everything is art, because things are only art with intention; if the intention is to make them art. But I can look at something as art. Without it being art. I understand that 20 Min is not art. It fully isn’t. But I can approach it like that. That’s one of the illest shits about art school – as impractical as it is, if you really do get something out of art school, what you should be getting is this sort of capability to be visually literate. Not just textually, but visually. And to be sonically literate also goes in line with a sort of visual literacy. Because everything goes back to sight in one way or another. So maybe the sculpture isn’t just an object that can do something – rather, I should say it’s an object that can do something and is purposefully useless.

But it is capable of doing something for someone else.

It produces an effect, or operates in the world somehow. I don’t know. Again, it’s one of those things like when Mark Fisher talks about capitalism – I don’t have an official definition, but I know it when I see it. One hundred percent.

I’m going to list five things, and you’re going to tell me if they’re sculptures or not.

Bet.

Febreze.

Mmm. It really depends. Like it itself, if I just saw it, no. If I just saw it on a shelf, definitely not. But I will say there’s a lot of kunst; kunst is the German word for art, that at least amidst my art friends, is an indicator of a type of work that looks a certain way. Febreze is kunst bait; it’s like a thing that you would see in a lot of kunst.

Milk.

Again, that’s another one. I’ve seen not just kunst, but a lot of art in general use milk; “the body,” or whatever. Itself? Definitely not, no way that’s a sculpture. No way Jose. But . . . it can be.

Macaroni and Cheese.

Well actually, hold up. I think because macaroni and cheese has like, a culinary aspect that’s super defined by its regionality, and has a very real specificity – it’s a fucking cultural landmark – to an extent, yeah, for sure. We can get into macaroni and cheese. There’s so many- I remember a couple months back, there were so many videos popping of white people making weird ass macaroni and cheese, with broccoli and carrots in it.

I’ve seen someone make it with peanuts. Acorns as well.

(Laughs) Like c’mon bro, that’s super outta pocket.

But yeah, how about acorns? Are those sculptures?

I mean, I like them as objects. I think that they are formally really nice-looking – you know, like you have this sort of polished sort of torpedo moment at the bottom half, and then at the top you sort of have this scaled reptilian beret. I mean the squirrel in Ice Age, he’d definitely say that it’s a sculpture. Like the way he holds it, it’s like that motherfucker – I forget his name – but that motherfucker who holds the ring in Lord of the Rings.

Socks.

Oh, yes. (Claps) One hundred percent. I’m one hundred percent sure. Two days ago, I literally had a tube sock nailed to the wall in my studio. I fucking love socks. A white tube sock with two stripes at the top, on some Spongebob shit – I love a good sock. I’m all here for socks. Socks are great objects.

Absolutely.

That’s also another sculpture-bait thing; like, I’ve seen a lot of work with socks – but I could give a fuck. Socks go nuts. Socks go crazy.

New York, especially Brooklyn, I’d say is one of few places – even in the United States in general – where the artistic synergy is off the charts. You have artists living on the same block as you, in the same neighborhood as you; the art scene is interconnected, for lack of a better term. Do you think that’s made you any more sound as a creator? Like if you grew up someplace in the middle of nowhere in Arizona, would you still be producing at this capacity?

I think if I was from somewhere like Arizona, I would just be a different person. I think I would still be making work; like if everything else is the same minus my accent or whatever – signifiers of my locality – if I was still the same person from Arizona, I would just be making different work.

What kind of stuff do you think you’d be making in Arizona?

If I was from there? I mean, I don’t want to get stereotypical with it, but I’d probably be working with a lot of sand. (Laughs) I think the illest – I said this all the time while I was at school too – it is such a privilege and a pleasure, not to fall into that corny I’m from New York shit, but to just be from Brooklyn. Just being from here, the friends I have now, I know I will have for life. You bring me and whoever to like, Germany, and motherfuckers are going to love us up-and-down all around, just because of how we move. Again, I don’t want to go into the New York centric shit like “oh, I’m from New York,” but I’m from New York. I’m from Brooklyn. It’s different out here. And I think one of the craziest things about it geographically is that if you really have your wits about you, and you’re not like, coming from old money or whatever, you could really have a seasoned life by the time you hit seventeen. You can meet all types of people; you can be in weird ass situations that just season you – and that’s due to the fact of how geographically compact New York is. And in that also, how partitioned it is, you know what I’m saying? Like in Brooklyn, you go to Park Slope, and then you go to Seagate by Coney Island. Two completely different fucking worlds. Twenty minutes away from each other.

That reminds me of this picture of the Taj Mahal I found. I don’t know if you’ve seen it before, but the Taj Mahal is here: you only ever see the beautiful side of it, with the grass and the esplanade.

The money shot.

Exactly. But directly behind it, there are slums. It’s straight up poverty. Let me see if I can find it. (I pull up the picture on my phone, and show Louis).

Yo.

It’s crazy.

Oh my God, that’s so hard. Whoa, that’s nuts.

And that’s the duality that’s so interesting about geography in general. Like you can walk to someplace- say you’re in the general neighborhood residence section of Washington D.C, if there is one. A walk to Pennsylvania Avenue is thirty minutes tops. But economically – socioeconomically – it would take years and years and years to get to that point.

Lifetimes. Eons.

Right? People don’t reach that in their lifetimes.

People don’t reach that in generations.

You know Jamaica Estates?

Yeah.

I could walk up that hill to Jamaica Estates in five minutes, but never ever see the status that defines it in my entire life.

I’ve said this before, and I stick by it: LA is a place that I fucking love. And I love it as a place, I know, because I’m a New Yorker, and LA is on an opposite end of the same spectrum as New York. it culturally presents a similar portrait, but it’s opposite because you can stretch your arms and have breathing room. The socioeconomic gap, New York puts it in this sort of echochamber, where you feel its reverberations immediately. Me and my best friend Gilberto from high school; he’s from Washington Heights, I’m from bumblefuck here – we go to some random crib on 72nd Street and Amsterdam, and the motherfuckers have a Jeff Koons just sitting on the table. Like what the literal fuck, you know what I’m saying? Like, that’s nuts. That’s fucking nuts. And all it took was taking a 1 Train somewhere and going on an elevator. Not even by car. Foot. I think that’s part of the reason why I have a wild pool of references, because I’ve dealt with a wide pool of references.

I’m very curious about the average day for you. Tell me about how that flows.

When I’m home here in Brooklyn, like in the studio, my favorite time of day to wake up is 10:30-11-ish. Usually eleven. I’d go out and grab my coffee from around the corner, and smoke my morning bogey, and just think about what I’ve got for the day. Maybe check my messages or whatever. And what I always do – on one of these yellow legal pads, I’ll write down what I want to get accomplished for the next day. It’s kind of sickening because it’s definitely on some grind culture shit, but I always put way more than I can actually accomplish, so I can never cross off my list. So I just sicken myself. But it keeps me working. Every day it’s like I’ve got a new challenge to uptake or whatever. What I intend to do for the day is very dependent on what music I play; whether it be paper maché or sewing, there’s different types of music for that. If I’m paper-machéing, because I’m sitting in one position for a long period of time, I’ll listen to something hard. Like either really hard minimalist techno like some Detroit shit like Jeff Mills, or Len Faki, or Death Grips.

Shout out Death Grips.

What is it that he said? He said . . . Yeah, Death Grips- on one song called On GP, MC Ride, he says “I’ve tried nothing, everything works.” That’s one of the most genius bars of all time.

There’s so much swag in that line.

It’s one of the most deftly – like D-E-F-T-L-Y – written things, like ever. Like, that is brilliant.

Is it something that you relate to?

Hell yeah. I have it written in my sketchbook, actually.

Explain that.

It goes hand-in-hand with all the shit I’ve been saying about the idea that nobody’s bored and everything’s boring. I’ve tried nothing, and everything works. There’s nothing to do, because everything is working as it should. Anything that diverts from that, I would say, to try is a fault in the system. To try is to fail. To do implies that you did it. Yeah. I’ve tried nothing; everything works – it’s a powerful line. Especially in hindsight, thinking about my violent, violent, violent, violent, violent – that’s five violents – depression, junior year at Cooper. That fucking bar just spoke to me. Spoke. Spoketh. To me. Yeah. Shout outs MC Ride, man.

Around this time last year, you were opening your show with Thomas (Blair). What was the emotion like at that point?

Fucking electric. You ever watch that movie Crank?

No.

It’s filmed like a porno, because everything is shot from the bottom up; the color’s extremely filtered and everything is very saturated, so it has this very yucky look to it. Basically, the guy is like a hitman or something like that. And to keep himself alive, he has to put his hands on these electrical sparks or some shit. Like, to charge himself up. That’s how I felt. I was so excited, but fuck, I was so exhausted, because it was my first time doing something like this in terms of relative scale. (Louis takes some time to answer a phone call. We get back about three minutes later.)

In general, nature is a really common aspect of a lot of the art you’ve been doing recently. Like the pictures you did with the sun and the magnifying glass, or trying to get the pigeons to shit on the sculpture you have outside. Is nature something you’ve always drawn inspiration from, or is it a newfound reverence that’s now manifesting itself in your art?

I actually have a really deep abhorrence for when people say they’re inspired by nature, because it’s really boring to me.

Corny?

Mad corny. I don’t really find nature that interesting, but I just think more so that there’s interesting things within it. My approach to it, which can get a little lofty sometimes, is that one can think of the more formally interesting things in nature as the ultimate readymade. I have a chewed piece of branch in the studio, that a beaver had chewed. I’ve been sitting on it for a long time; I spent a year not knowing what to do with it. I’ll show you right now. (Louis takes me into his studio, where there is a tree branch partially chewed from the bottom. About half of the tree bark is removed, making it white on one side and brown on the other.) See, it’s not necessarily that nature is interesting; it’s just that nature has interesting things in it. Again, me being interested in bird shit is because I wanted to approach mark-making in the same way that I would a readymade, in that I don’t set up the mark; I just set up the parameters for it to happen. So it’s less about my efforts for it, and it’s more about the gesture in and of itself. And also the implausibility of it too.

In the Brooklyn Rail thing, you also talked about sourdough bread. And you mentioned the role of the artist in society being a muse. What do you think that role is?

One thing to note is that nine times out of ten, my initial spark for a piece does not maintain itself as a conceptual center for it. It’s just the initial thought. So for this one, my initial thought was that I wanted to use bread for two reasons: One, during quarantine, I’d seen all these hippy dippy bumpkin white folk making bread from scratch, which I thought was a very strange enterprise.

Right, like why bread? Why toilet paper?

This is not the case across the board, but I see it in the same way I see it with the jogging. This . . . sort of like, this leisurely activity, for lack of a better phrase. Like a softened effort. Literally, bread is softened effort; that’s a calm bar. That’s not to say that the piece is racialized because of it, but it definitely has to do with that initial idea. And then two, I have a long mental list of objects, motifs, what have you, that I want to do something with. And sliced bread is one of them. It’s another kunst-bait thing, it’s like a trend in kunst, but also arts in general. My initial interest in it was that sliced bread is not so much about the object itself; it’s more about a feat of engineering. The actual object itself is more of a stand-in for an accomplishment in the industry, which was to manufacture sliced bread. It’s like the ultimate invention – you know, “the best thing since sliced bread,” that was something that kept ringing in my head. I wanted to deal with the sliced bread object as a site from which I could address failure in a different way, so what I wanted to do in an immediately visceral way was be like: Okay, so there’s sliced bread. Let me put it back together. In a very flamboyant Frankenstein kind of way. And from that, I found a new idea of addressing this concept of failure; illegibility, through this violent regression. To double down on its sliced-ness as sliced bread, and put it back together, but never take that away from it.

That element of the slice.

Yeah, they’re not like permanently glued together; they’re still like a modular unit. In a very anti-evolutionary sort of way, this is sort of a backwards approach to that idea. To take one step forward, and a hundred steps back. The way I’ve been thinking about it is like if you could throw a boomerang, and it leaves your field of vision, somehow enters the gates of hell, then comes back to you looking completely different but still functioning the same way.

Yeah, that’s a good analogy.

One of the recipes to make a good work of art, especially in sculpture, is to have something transform. That has always stuck with me. Because all of my work at Cooper Union was about things becoming other metaphors, and this visual conceptual eye candy that’s sort of positivistic that affirms itself over and over and over again, which, after a while, feels masturbatory. So with the sliced bread, I wanted to deal with transformation and becoming, but in a completely different name – like it doesn’t become something else; it maintains its inherent objectness as in what it was. I actually just shipped it out to LA. It’s going to be part of a very nice group show coming up on the sixteenth of January. It’s like my first outing in LA on some art shit, so it’s kind of a little landmark for me. But yeah. Thinking about regression in terms of development, about it being able to find a new sovereignty. To regress without being deprived of its inherent nature, whatever the object may be, would be to forge some semblance of some sort of sovereignty.

Do you believe in New Year’s resolutions?

Uhhhh . . . Yeah. I believe in resolutions in general, I think – which is funny, considering how much I am sort of weirded out by the process of aspirationality. But you know, on my birthday in 2019, my wish was to have a show. And I did. Like, miraculously. So I guess my resolution would be to be kinder to myself – to be better at that, shit is like a whole skill. That’s real craftsmanship, to be kinder to yourself but then not get lofty.

Yeah, there you go.

And then, I don’t know – I just want to . . . maintain the momentum. For me to get started, it’s very hard. But for me to keep momentum going, it’s very easy. Like with the initial slump and everything. I hate COVID. It sucks. COVID is trash, bro. COVID is garbage. So this isn’t my resolution, but more of a resolution for the world: I hope that this can be semi-over – which I don’t think will happen soon. We’ll see. But yeah, I don’t know. There’s a couple of milestones I want to hit; there’s a couple of things on my “bucket list” – that’s like the corny Brooklyn kid in me, the kid who made Facebook statuses in 2009 like “I’m lonely and she’ll never understand.” (Laughs). Stupid platitudes about life. That same kid in me is the same reason why I do believe in, like, a New Year’s Resolution, and I have a certain faith in those sorts of intangible things. But my resolution is simply to keep the momentum going.