Into the Chocolate Factory With Curtis Kulig

Much like Willy Wonka, Curtis Kulig appears to know more than anything else that spending time alone outlasts all of the momentary allures of glamour and glitz: studying the moment from a distance is always better than drowning in it up-close.

SAMUEL HYLAND

Curtis Kulig likes to eat alone. Having lived and worked out of New York City for what is soon to be two decades, as his freedom to cook late meals for himself has gradually dwindled, he has developed a growing tendency to embark on solo dinnertime restaurant excursions across the scenic cafes of his storied metropolitan stomping grounds. It’s not like he’s a loner, though – among a sprawling list of names on his rolodex are the rapper and model A$AP Nast, the prolific fashion designer Jeremy Scott, and several figures intertwined with Supreme’s winding rise to underground prominence. Rather, Curtis Kulig likes to eat alone because, that way, he can devote his time to observing people.

“Watching people in a restaurant setting is insane,” he tells me, sitting in a sunlit chair by an expansive window overlooking Kenmare Street in his Manhattan studio. “I could say, as an individual that eats by myself and just watches human nature… I don’t know if it’s being nosy, but I- I watch. I watch! Maybe I’m that weirdo in the corner watching, but I watch.”

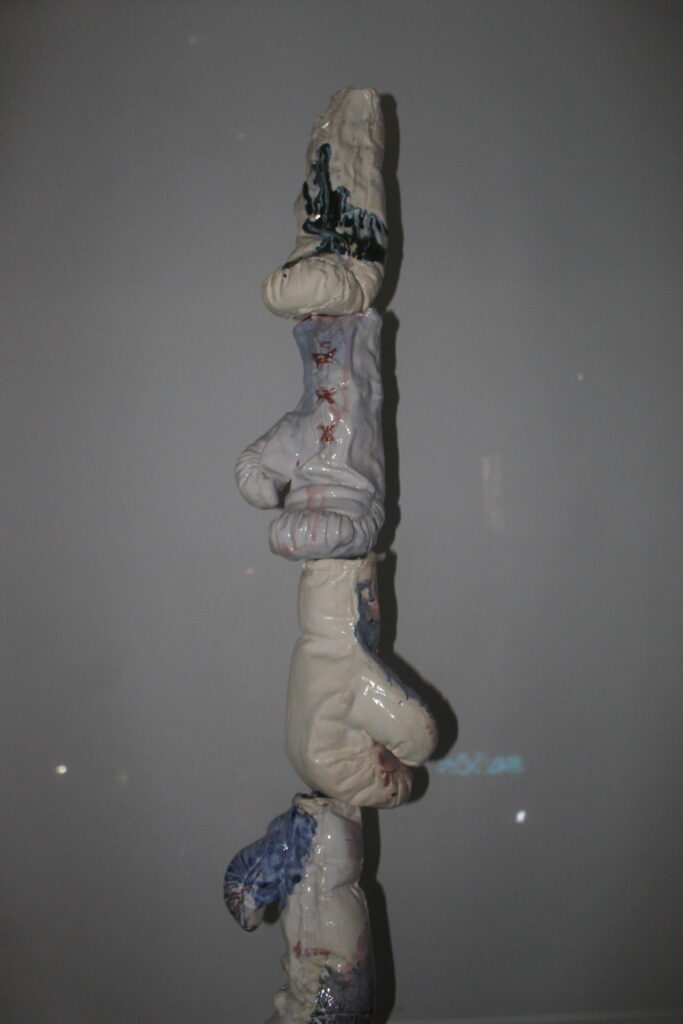

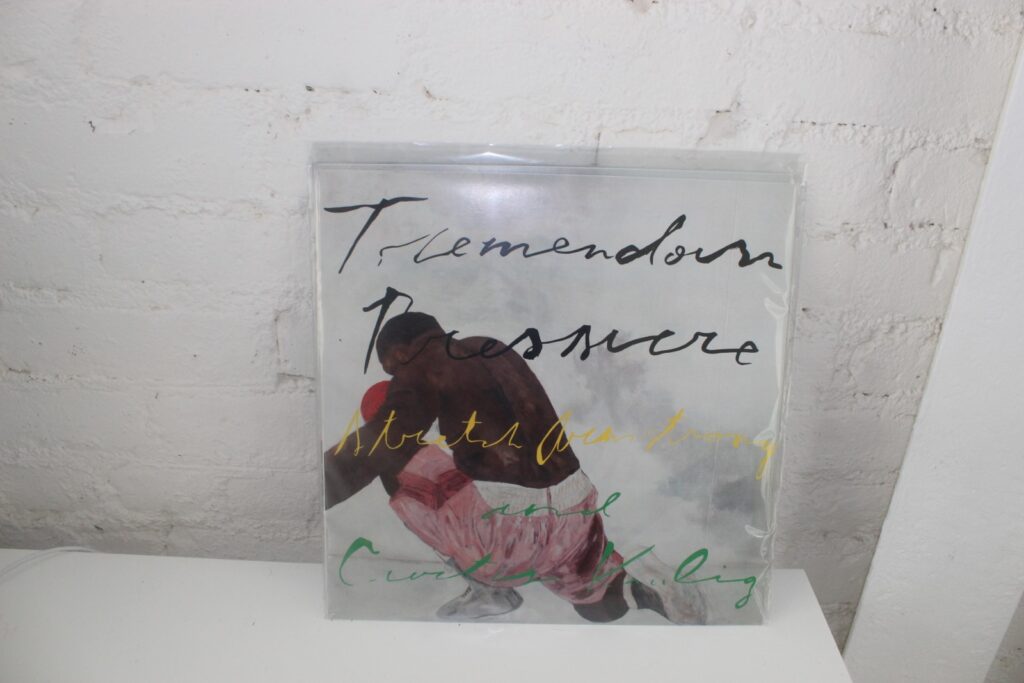

Kulig’s tendency to watch is something that has, even if it existed within him before he ever moved to NYC, only blossomed as a direct result of living in an urban jungle that never sleeps. As he sits cross-legged a few feet away from me in the aforementioned metal chair, there are a few images of grinning characters sprawled out on the table in front of him, along with some more stationed atop a nearby kitchen counter. Right there in the kitchen, adjacent to the images and seated amidst a gathering of sculpted boxing gloves, is an impressive film camera. Kulig himself is talkative and vibrant, an ostensibly childlike curiosity far overshadowing the smattering of gray hairs on his head – on his left arm, there’s a tattoo of Woodstock, Snoopy’s best friend in the childhood-darling Charlie Brown and Peanuts franchises. Whereas one would think that a high-level multidisciplinary artist of his stature would lounge in their creative space in expensive designer pieces and luxury footwear, Kulig is sporting a pair of jogging shorts and a vintage short-sleeve Carnival Cruise tee bearing the words “JACKPOT WINNER”. As casual as his presence has grown to become, both in the streets of New York City and in the halls of his studio, late-night party-of-one restaurant exoduses exist for Kulig as a gauge of sorts – a means of observing humanity in its most candid form, while simultaneously conducting de-facto litmus tests of where he fits within its folds.

“I can’t think of a different word than like- it’s a trip! Really. It’s like, you can’t make this shit up.”

The most common areas where Kulig finds himself disconnected on such evening dinner-slash-observation trips, are when pairs he observes eating together are momentarily split up because one has to go to the bathroom.

“I would say, it’s not about that part,” he starts, dismissing the sole idea of him eating alone as his main point. “It’s the stats: the statistic of two people eating together, and one of them getting up to use the restroom – the reaction of the other person that’s left alone. I would say… nnniiiiiinety eight percent of the time, within two or three seconds, they grab for their phone. Well, basically a hundred percent of the time. Every time.”

Being a proud product of the internet-savvy generation I was born into, I quickly jump to the defense. I try to justify this human tendency with the explanation that no one likes the feeling of being left hanging, and that the cell phone plays an undeniable role in mitigating the sensation of being lonely.

Kulig listens intently for a while, nodding and sitting still. Then, at the very moment that I finish my jumbled spiel, he opens his mouth to ask me something.

“Right – but why is it not okay to be left hanging?”

The question is one that seems to encompass his eclectic characteral makeup: Curtis Kulig is an artist whose work, at some points intentionally and at other points not so, is constantly coexistent with human beings. His public-facing artistic footprint – whether in the form of countless marks left throughout the neverending New York downtown, calculated thefts of “SHAME ON YOU” surveillance camera printouts in city shops for art shows of creative friends, or high-end fashion collaborations that may be sitting in your closet as you read this – is one that suggests a mastermind that thrives within the populace, extracting his energy solely from large crowds and the presence of a tangible audience. But, on the flip side, Kulig appears to know more than anything else that time spent alone outlasts all of the momentary allures of glamour and glitz: studying the moment from a distance is always better than drowning in it up-close.

This general intrigue with human nature is one of the many things that make me liken Curtis Kulig to Willy Wonka. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, I still argue today, isn’t primarily the childhood fantasyland that its packaging makes it out to be up-front; in greater part, it is an intricate study of homosapien tendencies carried out by a deranged chocolateer who, in carrying out his grand experiment, shines a light on some of humanity’s darkest crevices, with greed, gluttony, and pride being common extractions. But Kulig is also a lot like the fictional cocoa connoisseur in a very literal sense – When I arrive at his insanely cool studio right after picking up my high school diploma on a sticky, sweltering, Monday afternoon in late June, the first thing he does upon meeting me at the front door is hold out a thick hazelnut chocolate bar. “Want some chocolate?” he asks me.

Curtis Kulig’s studio blends into its Manhattan surroundings so seamlessly that on my way there, I walk past it three times. Its entrance, an unsuspecting door with a buzzer system at eye-level by its side, is made extremely missable by (1) a coating of white spray paint that blends it right in with the surrounding wall, and (2) an assemblage of black-and-white splotches of cursive textuals and faded brand stickers, each of them as perceivably undecipherable as they are assumably storied.

After he meets me outside at the conclusion of a brief neighborhood jog, with a hazelnut chocolate bar in my hand (it was very tasty), I follow Kulig up a surreal spiral staircase leading to his upper-level working area. There are a few windows in the stairwell region, and all of the walls are painted a slightly bluish gray color. At ground-level, upon opening the doorway, there are bicycles propped up against tight corners, a series of multicolored recycling cans, and a basketball sitting atop a bucket of art supplies. A few more flights up the staircase, there is a lofty stack of four years’ worth of New Yorker magazines that Kulig has been collecting, which – despite admitting to having only read about ten articles in total – he had been planning to make some sort of jarring artistic object out of at some point. A dim white overhead light gives the ascent to his studio entrance a sort of industrial glare; like the (first) elevator scene in Tim Burton’s 2005 Charlie and the Chocolate Factory remake, it seems like we’re on an endless, somewhat physically taxing trek to a single door behind which all the magic exists, and I just happen to be lucky enough to have a golden ticket.

Inside, Curtis Kulig’s studio is a sleek expanse of larger-than-life canvases, natural light, and seating areas neatly assorted here and there. On your left-hand side coming in, there is an entire wall covered by one of two hefty, closely-positioned pink-hued oil paintings. An assemblage of public swimming pool-reminiscent glass tiles fills in a small space between the ceiling and the wall’s vertical end. On your right, more long than wide, there is a lengthy-yet-spacious hallway that boasts, among other things, a modern kitchen, an equally modern bathroom, several paintings, a packed bookshelf, and a Moschino robe personally designed for Kulig by Jeremy Scott. Kulig has the place fixed up very nicely – it looks a lot like one of the swanky urban living spaces inhabited by tasteful, forward-thinking culture steerers who have shown up on your Instagram explore page at least one time in the past. He seems to be living the dream.

From a window, Kulig beckons across the street to an AC unit sticking out of a brick building, pointing me to the third-floor spot he lived in for eight years before he left for The Bowery, then subsequently got sucked right back into his old space. “This guy was living up here who I really didn’t know that well, but I would obviously see him around because he was in the neighborhood,” he explains, when I ask what pulled him back. “It was like a ‘hey, how are you’ sort of thing – just acquaintances, I guess. And at the time I had a studio on Broadway and Canal, and I was looking for a new one, and I ran into him on the street and he’s like ‘I’m moving to San Francisco.’ I asked him: ‘What are you doing with that place?’ I had never been here, but I just always looked at it from the window.” The studio’s previous owner was a hardworking film grip, who used the space to accommodate the vast selection of equipment such a position would require. (A film grip, says Gorilla Film, is “the person in charge of setting up equipment to support the camera, and on some sets, supporting lighting equipment [but not the actual lights. Never touch the actual lights]. It’s a physically demanding job where experience is invaluable.”) “The studio was dark when I came in,” Kulig recalls now. “But I cleaned everything out, painted everything white. It was mainly supposed to be a studio only, because I was looking for a studio at the time- and then once I came in here, I basically was like ‘I should just stay here as well,’ because I needed a new environment to create and I wanted to live with my work. Double bills wasn’t doing it for me anymore – it was becoming stressful. But now I’ve been here for four years.” When I half-jokingly muse to him that he’s living the life, he agrees with a matter-of-fact shrug. “I mean, it is. The city’s amazing, and the food’s amazing, and the people… it just works, you know what I mean?”

Having been a part of New York City’s artistic infrastructure for as long as he has, Kulig has developed a defining personal dichotomy: being in control, versus going with the flow. As a young person, he says, he was more gravitant to the latter, happily following whatever pathways unpredictable day-to-day circumstances carved out for him. As he has grown older, yet, and more elements of city life have gradually revealed themselves, he has learned to sway more in the direction of controlling all that he can – he’s gone from a big-city newcomer who operated chiefly on impulse, to a more corporate presence with one foot in the world of the Manhattan creative underground, and the other dipped into the ritzy waters of high art. Although such a transition has meant marvelous things professionally – there are so many collaborations with high-level business ventures to be managed that, for the last 10 years, he’s had a studio practice that consisted of multiple assistants – it has consequently forced him to shed some of his inner kid.

“It was mind-blowing, how quiet downtown was. But then there was this dichotomy where everything above street level was on and active. People experiencing the pandemic, waiting for what was to come next. Nobody was in the streets – it felt like you were walking through a closed set of a mobster film.”

Still, though, there remain times in Kulig’s life where traces of this inner child – curiosity being the most dramatic one – manage to peek through the cracks. As I chat with him on a cozy couch stationed across from the vast three-panel window display, one of them just so happens to be making some commotion at the door. Kulig excuses himself for a brief second, playfully muttering something about a “Jack.” I expect him to open the door to another adult friend, perhaps a fellow artist, a neighbor from a few floors down, or maybe a landlord he’s got a chill relationship with.

“Are you allergic to cats?” he asks me.

Before the word “no” leaves my mouth, a tiny grayish American Shorthair is sniffing at my leg.

“He’s a rescue from Staten Island,” Kulig explains, starting to walk me through a brief history of his relationship with the pet. When Hurricane Sandy ravaged a large portion of lower New York in late 2012, a nature-oriented friend of Kulig’s championed a grassroots animal rescue operation. He offered him the cat, and – although Kulig was initially hesitant to accept – he went with the flow: fast-forward to present day, and the artist-feline duo are going nearly a decade strong.

Jack does a lot of screaming. The cat opens his mouth wide in yawn-like mini-roars, bearing a set of sharp fangs that are quite threatening to squirrel enthusiasts such as myself. He does this about five times per minute. In short time, it goes from a sonic intrusion into our conversation, to stray noise that blends right in with the rest of the city commotion in the background. “I don’t know what happened with him with the yelling – this is something that’s happened with him (over) the last three years,” Kulig mentions, puzzled. When I suggest that if I were to suffer through both Hurricane Sandy, and the COVID-19 pandemic, I would be screaming too, he agrees with a chuckle.

Kulig wasn’t in New York for the September 11 attacks, but still, he has vividly experienced some of the darkest months in the city’s history. The early stages of the pandemic in New York brought forth mass paranoia, with nearly all inhabitants rush-adapting to fully indoor lifestyles while only the bravest – and by the bravest, I mean the homeless – remained on the streets. Kulig, however, often used these dark nights to go on adventurous bike rides through Little Italy. “Really late at night, I would go on a bike ride and smoke a cigarette at one in the morning,” he says excitedly, after we talk a little bit about how picturesque the city is. “It was mind-blowing, how quiet downtown was. But then there was this dichotomy where everything above street level was on and active. People experiencing the pandemic, waiting for what was to come next. Nobody was in the streets – it felt like you were walking through a closed set of a mobster film. Lil’ Italy anyway. It was trippy.”

Trippy is a word Kulig uses often, and I only start to catch on when we continue our conversation in a shady rooftop area he’s set up very nicely a few stairs above his workspace. I remark that he uses the word a lot after he says that it’s a “trippy world” that we’re living in.

“I can’t think of a different word than like- it’s a trip!” he laughs, behind swirls of cigarette smoke. “Really. It’s like, you can’t make this shit up.”

I ask him to tell me the trippiest thing he’s ever experienced.

“I don’t know, life – it’s just like, I don’t know. Life, plants; I look at plants like Oh my God.” He beckons around our surrounding area towards the beautiful expanse of rooftop greenery that encircles us. “I look at these trees in the winter that are skeletons, and then springtime just happens, and peaches come out of the branches that you can consume, and that are delicious and make your taste buds do things,” he says, with a dreamy intrigue.

It seems to be an impossible contrast – a public-facing artist whose stomping grounds are the most illustrious man-made city in the United States, in an intimate relationship with the very Earth-born nature such a setting is inherently opposite of – but in Kulig’s case, it registers just as another unconventional quirk in his Wonka-esque affect: it doesn’t matter if it doesn’t make sense. And more often than not for him, it’s the things that don’t make sense that are the most interesting. As much as Curtis Kulig is successful, he’s not nearly as focused on being accomplished as he is on being curious. While the tightrope between being successful and being interesting is often a one-or-the-other dynamic for most, Curtis Kulig manages to maintain both titles at the same time – and, just like Willy Wonka, seemingly effortlessly so.

Something that interests me – and, I soon learn, him as well – is a singular metal chair stationed at the far end of the balcony. It’s a definite no-go for people who are afraid of heights (I can barely follow him to the chair without picturing myself falling to my death because of one ill-fated sway). But while the spot is a place of terror for me, for Kulig, it’s a place of serenity. “I don’t like a lot of singular things. Something that freaks me out is when I see a singular shoe on the street – it just puts me off. But some things work really well singularly. That chair is one of them.” The chair grants an inspiring view of the slanted Manhattan street Kulig’s studio rests upon, a minute singular blue presence in a universe of jagged, industrial, skyward shards.

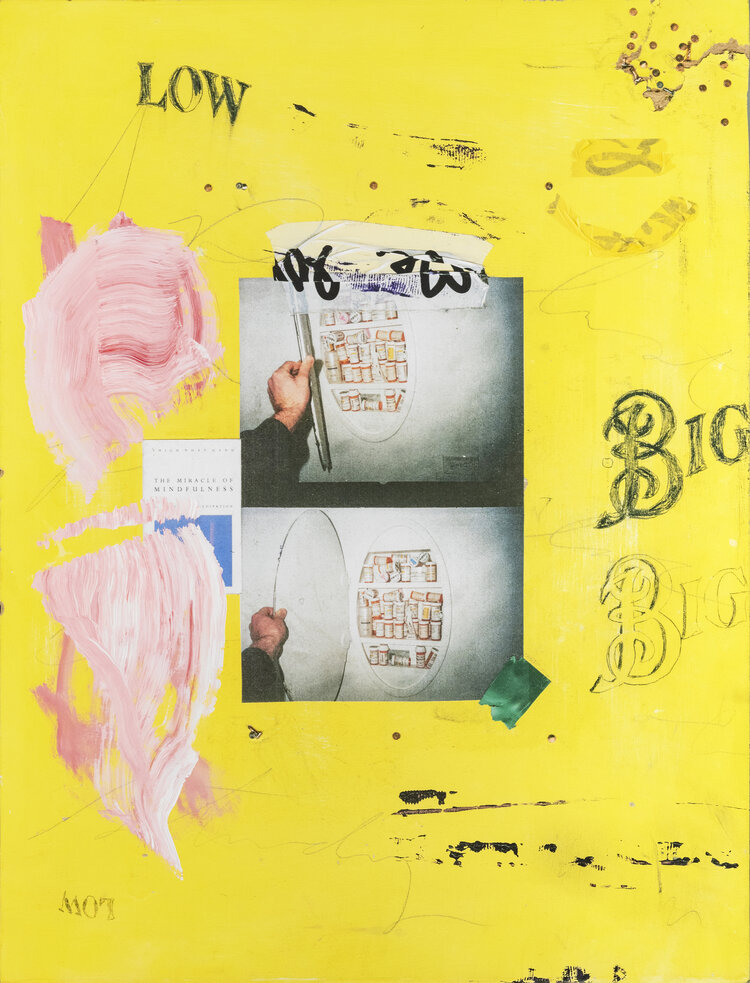

This past April, perpendicular to the lonely gospel of the chair, Kulig published a book, Loud Money, alongside longtime friend and prolific 72-year-old British poet Max Blagg. The pair first crossed paths in 2012, when Kulig commissioned Blagg to pen a sermon for a religiously-themed performance art piece he was scheduled to showcase at the Museum of Modern Art. (The aforementioned custom Jeremy Scott robe was what he planned on wearing – albeit nothing came of the idea when MoMA canceled the show for its controversial nature.) The two stayed in touch over the near-decade that passed since the collaboration, and Loud Money exists as a scrapbook of their unconventional connection, backgrounded by an overarching theme of life in cities like Manhattan.

“sometimes I wonder why I persist in NYC,” one Blagg poem entitled Geri Miller Is Alive And Well reads, “especially in the heat of summer, immersed in the reek of Chinatown and its phlegm-coated pavements, enraged by rats nesting in my parked car, the Olympic size pool now being installed on the roof of the new building that has erased my southern view…”

It’s reminiscent of something one cannot help but think: New York City has changed a great deal around Kulig, and he logically has every reason in the book to feel some form of jadedness. Yet, where most creatives scoff at the world as it evolves around them, Kulig, as he does with most of what populates his life, sees the revolution as the most interesting thing on Earth – something to be embraced with an open mind, rather than scorned with shaking fists.

He and I talk a lot about change over the course of several hours. After a flurry of examples we bring up about humanity’s natural resistance to it – including uprisings against the implementation of seatbelts in the 20th Century, and similar uprisings against mask mandates in present-day – he takes a second to ponder his own relationship with the concept.

“I’m really aware of being in the now – truly being present, staying off the phone so much, and making the best of it,” he tells me, standing by a wall leading up to his kitchen. “What else can you do?”

🖼️ 🖼️ 🖼️

Before Curtis Kulig’s primary medium was the canvas, it was the camera. As he has transitioned from a lifestyle of going wherever the wind took him – rapid treks across the globe for months at a time – to a chiller day-to-day with heightened room for introspection, a lot of the pressure to document life as it flashed by has eased. But in the years that saw him first begin to come into his own as a creative figure, it was the art of the photograph that provided a much-needed niche.

“It was the child in me running in the other direction of my family, being painters, and drawers, and sculptors,” he says of his beginnings. “In a very traditional sense. They were so talented. So talented. Their skillset surpassed anyone I was paying attention to at the time. So growing up around that academic side didn’t appeal to me till I arrived in NYC, where I started attending New York Art Academy. It’s not that I didn’t want to be part of that, I just didn’t feel like I could.”

Today, it’s a scorching hot afternoon in July when I arrive at Kulig’s workspace, and unlike the first time I visited, he’s not coming in from a neighborhood jog. I have to use the buzzer system. About a half hour after coming in, I learn what exists on the other side of the silver button by the entrance: the buzzer operates almost as a sort of futuristic peephole, displaying the faces of visitors on an electronic screen, and giving Kulig the option to either let them in, or keep the door locked shut. The photographic buzzer system is one of many lingering traces of its operator’s past life, a sleek instrument of visual documentation peeking out from a background of oil paint and canvases like a shiny stock car at the Belmont Stakes. When Kulig shows me my picture on the device, I am between the words EXTERNAL UNIT CALL and WAITING FOR REPLY, a semi-pixelated humanoid with a phone pressed to its ear. As normal of a sight as it is for Kulig, it is a jarring image for someone who is quick to whip a phone out when his company goes to the bathroom at a restaurant. So much has been bathed in the artificial, that the real almost feels fake. Curtis Kulig exists in the unfiltered reality that technological advancements have made obsolete – and, strangely, using the same exact technology that washes this version of life away, he has no problem telling its story.

“I swear to you: every time I went to that pool, I would be like ‘Thank God for this pool existing.’ I mean, what’s better than swimming; sauna; cold shower; and then eating some fresh fruit?”

A lot has changed with the concept of studio-centric documentation over the artistic history of Curtis Kulig’s New York hometown: chief among them, the role of the polaroid. Perhaps the most prolific snapshot of its use is Andy Warhol, the white-haired, bespectacled cultural mainstay who dominated the limelight of his respective scene even in years following his death. Andy Warhol operated out of three corporate buildings, each dubbed ‘The Warhol Factory,’ over a decades-long period lasting roughly from 1962 to 1984. It was in these buildings that he would play host to a slew of creative ventures – underground movie filmings, experimental recording sessions for art rock albums that he executive-produced, forward-thinking on-canvas collaborations – and for nearly every high-profile visitor that walked through the factory doors, there was a strategically-taken polaroid photograph to show for it. In one photo, Jean-Michel Basquiat playfully pulls his eye sockets downward, pinky fingers in his nostrils, ring fingers holding his mouth open horizontally. Another shot features a steely-eyed John Lennon peering straight at the camera through orange-tinted lenses; one more sees a shirtless Muhammad Ali looking off to a distance with a half-mouthed snarl and a wild countenance. The polaroids – all 20,000 of them – were moreso status markers than photography practice. (Next time you see a vintage-looking celebrity polaroid on an aesthetic-heavy Instagram archive account, try to look into who shot the photo. More than likely, it was Andy Warhol.)

Exactly this, though – the overarching motive to affirm one’s status – was the egocentric side of Warhol that led many in New York to resent him. Although Kulig respects the legacy that Warhol left, he is no stranger to its selfish imprints.

“It’s like, ‘Congratulations, you hung out with a bunch of famous people,’” he says with a sarcastic smirk. “I get it. I get it – like, it’s cool. Like, ‘Oh, a picture of Blondie or Edie in the Factory again.’ But the real – to really over conceptualize it… it just feels like an ego trip. Like ‘This is how many friends I have.’ ‘This is the amount of celebrities in my milieu.’ I’ve heard stories about how calculated he was, making sure he would be seated by Madonna at dinners.” (For the record, Kulig does like the series of “Shadow” paintings Warhol created from 1978-1979, though.)

In the art world, ego is something that, although it existed long before modernity with the likes of Raphael and Michaelangelo, took on an entirely new form as pop culture writ large leaned more towards celebrity and less towards output. In the neo-expressionist era that Jean-Michel Basquiat championed, for instance, he became just as much of a fascination to consumers as his art was – no matter how reclusive he desired to be, the growing cult-of-personality he attracted made it increasingly less possible for him to separate himself from his work. It was the artists, then, that were filling the gaping cultural chasm that musicians and actors often seem to today; and those shifts in proximity to celebrity culture have translated to an egocentrism that still presents itself in art scenes decades removed from the renaissance.

Curtis Kulig is an easygoing person. He’s reflective about what’s around him at any given moment; he’ll hear you out when you’re talking absolute gibberish; you probably won’t leave his studio without a gourmet chocolate bar. But not having an overbearing ego quickly becomes a roadblock in an ever-changing art world following the same ebbs and flows of an increasingly ego-obsessed society. It helps to picture it as that aforementioned tightrope between filtered and unfiltered realities: the art world lives in one, and Kulig lives in another. Intersections are difficult to come by.

“Before that, I was just the Curtis Show. Once you get pushed off that pedestal, things become a lot more real.”

“That’s what makes it interesting, too,” he muses over the loud sounds of revving sanitation trucks, sitting back in the sunlit rooftop area. “It evokes emotion. It upsets me. Like, why do people have to exist like that?”

The allure of diving headfirst into the society of high art is essentially magnetic for someone like Kulig. Yet – just like the universe of competing chocolatiers was for Willy Wonka – it exists as just one more rat-race he has the temperance to abstain from, often opting to study from afar and dip his feet in the waters when they calm a bit, rather than jump right in and be carried away upstream. A solid typification of the passive-aggressive dichotomy comes when, as I’m getting ready to leave, Kulig sifts through an overhead storage space that he uses to stash luxury fashion pieces produced via both his own brand – Love – and collaborations with other big-name entities. When I ask him how many of these partnerships are actively going on, he chuckles, and says it’s too much to stick a number to.

Where the busybody business side of Kulig produces at such a high capacity, though, the easygoing humanitarian side also finds ways to peek through the cracks.

“I get boxes of clothing from my brand in Korea every season, and I usually drop the majority off at the mission,” he says semi-frantically. It’s a heartwarming image that looks a lot like an all-year-round Christmas miracle: picture a prolific designer, no Instagram-ready cameras nearby, donating bags upon bags of luxury apparel to a mission center packed to the brim with hand-me-downs.

This goodwill does not mean that Kulig’s corporate face disappears forever. Kulig is speaking semi-frantically, because he has a business meeting in two minutes.

Although today, Curtis Kulig is an incredibly chill character who gives out free chocolate and observes human nature for fun, getting to such a point was quite the journey – perhaps the longest he’s taken.

He is not ashamed to admit that he was a bad kid. (So much so, that when he grew older, he took it upon himself to personally apologize to his mom for what he put her through. “It was maybe more for me than it was for her,” he told me in our first meeting. “All the bullshit that I put her through… was… a lot.”) Growing up in North Dakota, there was not the synergetic artistic pull of a big city to lure him into his calling at an early age. In place of the various creative niches of New York and Los Angeles, where he stayed for a few years in the early aughts, the North Dakota of his childhood was best known for its volatile punk rock scene. His community was just as radical as the music it fostered, too: practically all political leanings were extreme, grounded in rebellion and vehement disillusionment with government.

Kulig himself quickly fell into the fast-paced lifestyle that such surroundings evoked. He partied often, sometimes getting into physical altercations, and often having brush-ups with law enforcement. He was a crafty kid who regularly got out of trouble with his mouth; and, for a lot of the serious trouble that he couldn’t talk his way out of, his age did the trick: he was still considered a minor, and therefore couldn’t be fully prosecuted for most of the infractions he committed.

“Swimming is the one thing that is a constant for me, where, like painting, my mindset instantly switches to feeling alive again.”

But, he tells me, there were two general wake-up calls that contributed to his transformation: one of them being the first time that neither his wit, nor his age, could get him out of the mess that he had dug himself into.

“It was silly,” he starts, upbeat jazz music from his speaker ironically contrasting with the serious subject matter at hand. “It’s not like I’m necessarily a fighter, but, like… it was really regular stuff that went on in North Dakota. Kids would get drinks or whatever, and there would be a fight.”

On the night that the incident in question happened, Kulig and his friends had become wrapped up in a chase, and then a confrontation. Everyone involved in the matter had a hand in what followed. But when police showed up, Kulig, not knowing the severity of such a decision, opted to take all of his friends’ charges for himself. He was eighteen years old – the town judge had been waiting on this moment for a very long time.

“It was the first time I realized ‘I no longer have my freedom,’” Kulig says of his time in jail. “My parents aren’t getting me out of it this time. I’m not talking myself out of it this time. I can say or do anything I want, but the bottom line is that I really lost my freedom this time. I’m stuck in a cell. That was my first instance of really getting knocked off my feet.”

The second and most effective wake-up call Kulig underwent came years later, when he followed a friend to live in Los Angeles, California, for some of his early twenties. Although his small stint in jail shook him up a bit, it was not enough to permanently remove him from his old lifestyle. Soon enough, he had gone right back into a day-to-day of partying, living freely, and throwing caution to the wind. But there came a point where his body couldn’t take it anymore.

Kulig speaks with the super chill aura of a baseball coach who could have made it to the majors had it not been for a career-ending ACL injury, the kind of breezy affect that washes over surfboard-toting beach movie stars and gym teachers that are far too cool to be doing what they’re doing. On the rooftop, he details to me what such a backstory entails in his own case: as the days passed, his body started giving up on him. He felt his energy levels drop. He couldn’t do things that he used to be able to do. Talking about it, he takes long pauses, looking downward towards an ashtray at the foot of the outdoor table before him.

As he goes from hot showers, to cold showers, to saunas, to the remarkable ability of Wim Hof to hold his breath underwater for long periods of time, to the serenity of floating in a basin, then back to hot and cold showers, there is a point where I stop asking questions.

“That grounded me more than getting locked up. Locked up, I still had my health. I got out, and I was like ‘Whatever, I’m doing my thing.’ But you take somebody’s health away? You get shot in the gut, or the spleen, or wherever Warhol got shot? You definitely… everything flashes a little bit,” he says, between glances over the balcony.

“I think that after I lost my health, that’s when I got on a path of trying to take everything a little bit slower. And just registering human behavior in general. How to act, treating people the right way, and talking to people the right way – I mean, basically the analogy of just ‘treat people the way that you want to be treated.’ Before that, I was just the Curtis Show. Once you get pushed off that pedestal, things become a lot more real.”

As of right now, Kulig isn’t the young, carefree version of himself he used to be, and if there’s any indicator of how drastic of a turnaround he has made, it’s in what he wears: both over email and in-person, he confesses to me that he’s a snob about high-end footwear and furniture. Still, though, each time that I meet with him, he seems very allegiant to a uniform of exercise shorts, white tee shirts, and running sneakers. This is not because it’s fashionable – it’s because he’s constantly working out in some way, shape, or form. When I meet with him today, for one, Game 1 of the NBA Finals is slated for later on in the evening, and – even though he can’t identify a majority of the players I bring up – he is fresh off of an afternoon of long hours spent shooting hoops with a friend. When I ask about a series of yellow paintings he spent some time working on years ago, in removing the canvases and miscellaneous objects that stand in front of them, he uncovers an impressive interactive fitness mirror he purchased during the early stages of the pandemic. In many early interviews of his you can find online, too, it is a common discovery that it does not take long for a sit-down conversation with him to turn into a fun walking – or jogging – trip into the New York City downtown.

When our conversation somehow shifts to the art of arguing with imaginary haters in the shower, Kulig is beyond excited to talk about water. As he goes from hot showers, to cold showers, to saunas, to the remarkable ability of Wim Hof to hold his breath underwater for long periods of time, to the serenity of floating in a basin, then back to hot and cold showers, there is a point where I stop asking questions. I listen to him talk about a local YMCA swimming pool he used to frequent – absolutely not something he picked up over quarantine, he insists – that recently closed its doors.

“I would go swim, I’d get in the sauna, I’d take a cold shower, I’d go back in the sauna, take another cold shower, and then there was a market right by the gym, and I would go and get fresh pineapple,” he recounts, reciting each step in the ritual with the speed of a mother going over a grocery list. “Swimming is the one thing that is a constant for me, where, like painting, my mindset instantly switches to feeling alive again.”

When the Chinatown YMCA closed up shop at the pandemic’s beginning, it represented the removal of Kulig’s routine. He had grown so attached to it, even, that one day, he emailed the establishment to check up on the status of the pool (it wasn’t coming back anytime soon). Much like is the case with everything else Kulig has witnessed over the course of his career, whether the pool is active or not, it’s the little things like it that he finds interesting. And at the end of the day, it’s the interesting things that – even more than the things that guarantee straightforward success – keep the Chocolate Factory in business.

“I did not need COVID to teach me a lesson that ‘Oh you need to be grateful that you have swimming,’” he tells me through a grin, leaning back on a bench and looking skyward. “Every time I went to the pool, I thought to myself: ‘I am so grateful that this exists.’ Swimming, sauna, cold shower, sauna again, then consuming some fresh fruit and fresh water – this is as good as it gets.”