A humble documentarian takes on a tyrannical medium.

SAMUEL HYLAND

In the 258th and final film photograph taken by Devlin “Devlyn” Claro on a recent summer excursion to Italy, well-preserved frescoes fade eerily from the beige walls of a sunlit church building. The scene is, in a strange way, viscerally haunting: with no discernible life-forms in the artworks’ collective vicinity besides a window-shaped fleck of sunlight sitting off to the side, the barren shot registers as if on the precipice of a certain ultimate voyeurism, a stolen glimpse at something preternatural none of us are remotely allowed to be witnessing. As it turns out, Claro was not, in fact, allowed to be witnessing the moment either—he had stumbled into the church with a tripod and begun sporadically shooting like a tone-deaf tourist, until, moments after he took the aforementioned photo, a pissed-off minister approached him and threatened to destroy his equipment the second he dared snap one more. Okay… maybe that last part didn’t actually happen. But it might as well have: in a spurt of bad luck that felt more like divine intervention, Claro would ultimately go on to break the camera, hours later, on his own. “Sigh, I dropped my Mamiya,” he recounted in an email this past August, a week or so into his trip. “Thought I had it strapped around my neck before getting up to switch to a better table at a restaurant – I’m embarrassed that it happened in an effort to do such a stupid thing in the first place.”

“It’s beautiful, and it’s anxious, and it’s hard to look at. And my shadow’s over it. I never acknowledge myself in my photos, and there I am.”

Claro, a contemplative 20-something artist from Queens, visited Italy for the first time this past summer in efforts to both reconnect with his homeland, and hone his sprawling documentation-driven practice. Over the past several years, his name has made intermittent cameos in varying notable locations—from the YouTube credits of popular music videos, to the lofty photo bylines of respected magazines—but as of right now, he’s looking to focus less on where his name happens to land, and more on where his vision can deliberately steer it. This begins, in a very direct sense, with the literal practice of naming. His birth name is Devlin Claro Resetar, but Devlyn Claro, his current tag-of-choice, (1) sounds a tiny bit cooler and (2) allows for a subliminal word-scramble shout-out to the city that molded him. On another front, more relevant to his Italian exodus, the process of vision-steering also entails a need to actively pursue narratives and document them, with intention, wherever they may reveal themselves on a daily basis. Three months in from his return to New York, he’s just as adamant about life being a movie, though the process of capturing its layered scenes remains just as tedious.

“That day, there was a man coming from Germany named Karl Hudson,” he narrates between chomps of a bite-sized breakfast taco, running me through a cinematic weekend that saw him get locked out of his house, haul gorilla-sized vintage media machinery up his to his mom’s attic under the watch of a mysterious technology genius, and sit in couches Bill Gates may or may not have fucked on. It’s a little before noon in a homely neighborhood park bordering his Brooklyn apartment, and despite it being uncharacteristically warm for November, Claro is considerably layered up. An open-faced balaclava and crimson dome cap obscure much of his head; neck-down, he’s wearing a Prada puffer coat over a cozy-looking corduroy zip-up jacket over a thick Dartmouth crewneck. “Karl Hudson is some kind of legend in the photo community,” he explains, “because he single-handedly has kept alive Heidelberg scanners. Heidelberg is a company that went under in 2002, when digital photography was making its way towards replacing everything analog. He was an engineer there, so he knows how all the machines work.”

Hudson, an energetic 60 year-old who makes routine pilgrimages from Germany to spread his hyper-niche expertise to the less-enlightened, was slated to help Claro install the coveted-but-humongous piece of equipment in a work-in-progress darkroom stationed at his mom’s house. Long story short—I swear I’m going to get this all into one sentence—Claro pulled together a scrappy bunch of friends, got yelled at in a Home Depot while looking for machinery that could have potentially made the lugging process easier, collaborated with said friends to haul the scanner up his parents’ staircase while they looked on in understandable confusion (They had no idea who Hudson was or what he was doing here), finally got the scanner to the attic, spent ten hours of the following day setting it up with Hudson, got sick, got better, and now, on this Wednesday morning, has taken me along for a coffee run packed with existential Drake discourse before finally settling on a sunlit bench, eyes darting through skinny wire frames and occasionally meeting the glances of curious dog-walking passersby. “I’m a meandering son of a bitch,” he says, with a self-deprecating guffaw.

“If you asked me to take a photo right now, of you, of us, of something in this park, I can make something that will suffice. I know that. But if you asked me what it meant?”

The long-term goal, though, is to not to be. The first thing Claro did when he got back from Italy was something he’s always known to do: work. Like any artist, he prizes the prospect of practicing his craft while also putting money in his pocket, and between all sorts of freelance gigs, odd-job hustles and one-off stints spanning from August to this article, he’s gotten to do truckloads of just that. But being an artist by trade is different from being an artist by intention, and as the blazing Italian Sun that defined his summer fades into the unforgiving New York winter that’s long defined his grind, the crucial distinction is becoming both more clear, and more urgent for him to make. Though both titles allow Claro the role of “artist,” only one allows him to wield it on his own terms. More and more, his “by-trade” suffix is tightening around him, and the time is running short until he outgrows it.

Upon hearing the slightest beginning of a question about the most recent photo he took with self-directed intention, he hurriedly pulls up one of several hefty Dropbox folders on his phone and scrolls until he finds an image of a dead bird. The deceased is a white-flecked pigeon sprawled out on the pavement outside Claro’s apartment in a dramatic quasi-crucifixion; a half-dry puddle of brownish liquid pools beneath its opened beak, and the crouching, headphones-clad silhouette of its autopsy photographer casts a haunting shadow by its side. “I’m walking, like two blocks away, and I’m like Fuck, I gotta go back and take that picture,” he says, narrating his infinite scroll through mines of .jpegs. A few more seconds pass, and he turns the screen to me. “The way that this motherfucker is splayed out like that. Poor fucking thing. But this captures a lot of what I want to capture. It’s beautiful, and it’s anxious, and it’s hard to look at. And my shadow’s over it. I never acknowledge myself in my photos, and there I am.

“I really need to do a full pivot,” he continues. “If you asked me to take a photo right now, of you, of us, of something in this park, I can make something that will suffice. I know that. But if you asked me what it meant?”

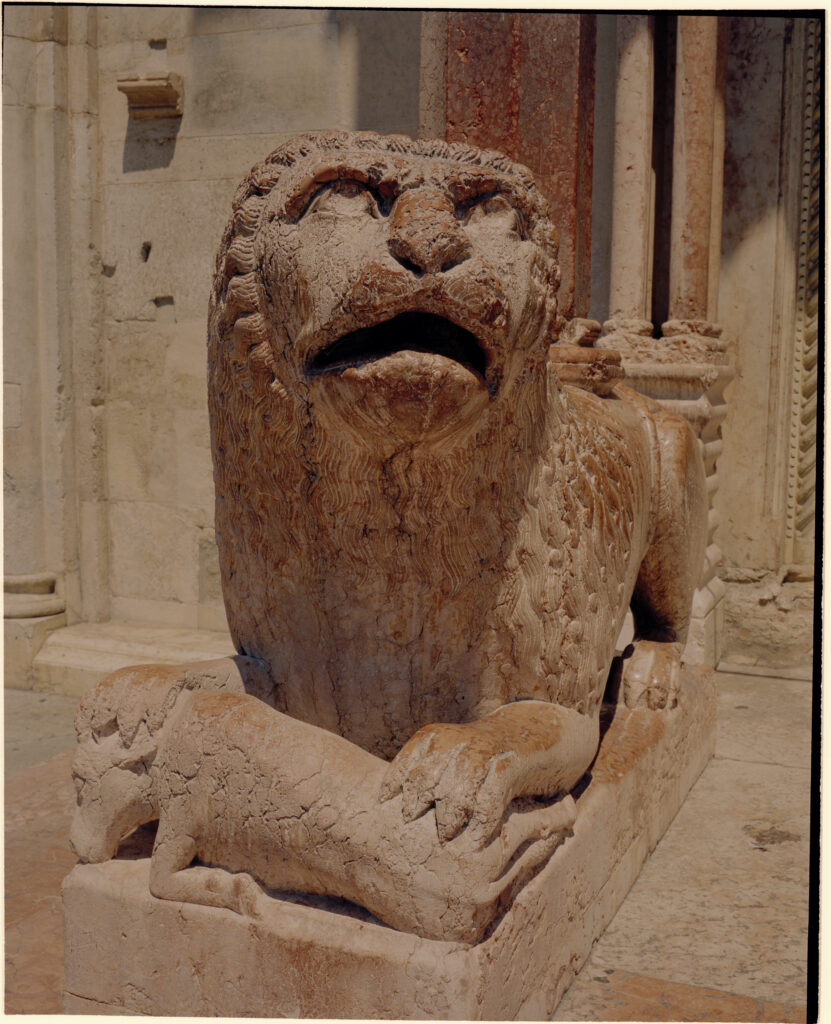

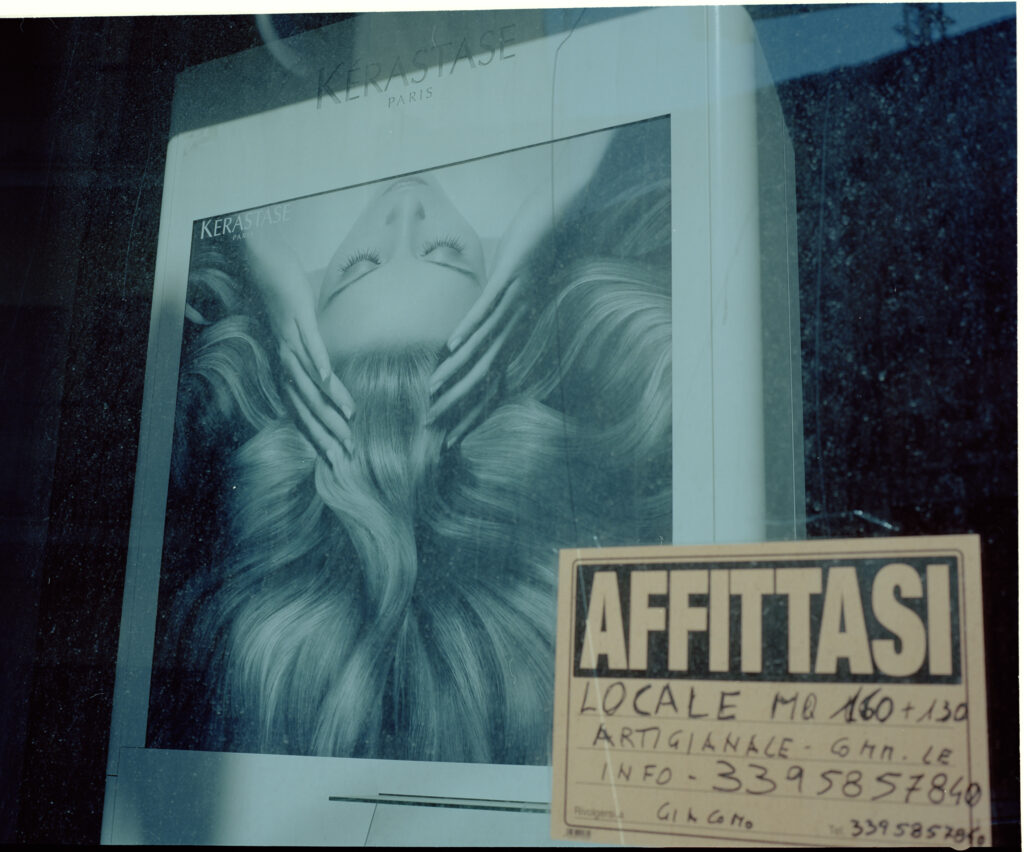

Something Claro has long been intent about, especially following his time in Italy, is incidental photography—a behind-the-lens mindset popularized by the deceased Italian artist Luigi Ghirri, wherein moments are documented more for their aesthetic open-endedness than for any specific theme[s] they might otherwise be used to evoke. When I visited Claro at his apartment a few days after his return New York, he scrolled through a large cache of images from the trip on a hulking old iMac, explaining, between modest sips of reheated coffee, that much of them were cut with similar intention-devoid rhetoric. He had been shooting photos that simply looked interesting—up to the very end, when the aforementioned hypothetical angry clergyman nearly destroyed his Mamiya before he himself got the chance to—and in exegeting them for me that afternoon in late August, was up-front and matter-of-fact about the simplistic narrative not having changed post-travel. Many of the photos he showed me eschewed concrete narratives for abstract visual platitudes. One considerable collection focused on a group of taxidermied seals on display at a natural history museum; another series featured odd-looking rocks on a beach; many centered colorful natural phenomena foreign to the grimy streets of New York City.

The question, though, becomes one of whether there is ample room for both scopes—stumbling into moments of artistry like he did in Italy, and commanding them like he wants to do long-term—to coexist in Claro’s artistic identity, rather than just one or the other. Before he answers that for himself in due time, the premiere brand of coexistence he’s focused on curating, at present, is between people. It’s why he thought the Hudson-scanner-saga was as beautiful as it was hilarious: in grand, sitcom-level fashion, characters who furnished the furthest possible corners of his life committed to one endeavor together, in one space, and accomplished something nearly impossible by each others’ sides.

It’s also a reason why he both enjoys watching, and hopes to create, films that can be enjoyed communally. “I love that movies are a way to bring people from different friend groups together,” he says. “I have created so many friendships in my life between people who otherwise never would have been together, and I see them blossom, and I think that’s one of the best byproducts of what I do. I’m speaking very vaguely, like I’m a fucking pastor or something—but you can sell being too cool for someone. I don’t know if you can sell what I’m talking about: but I just think it’s more important to try to understand each other.”

🎥🎥🎥

“You can make a movie without having to be responsible for the seconds in-between.”

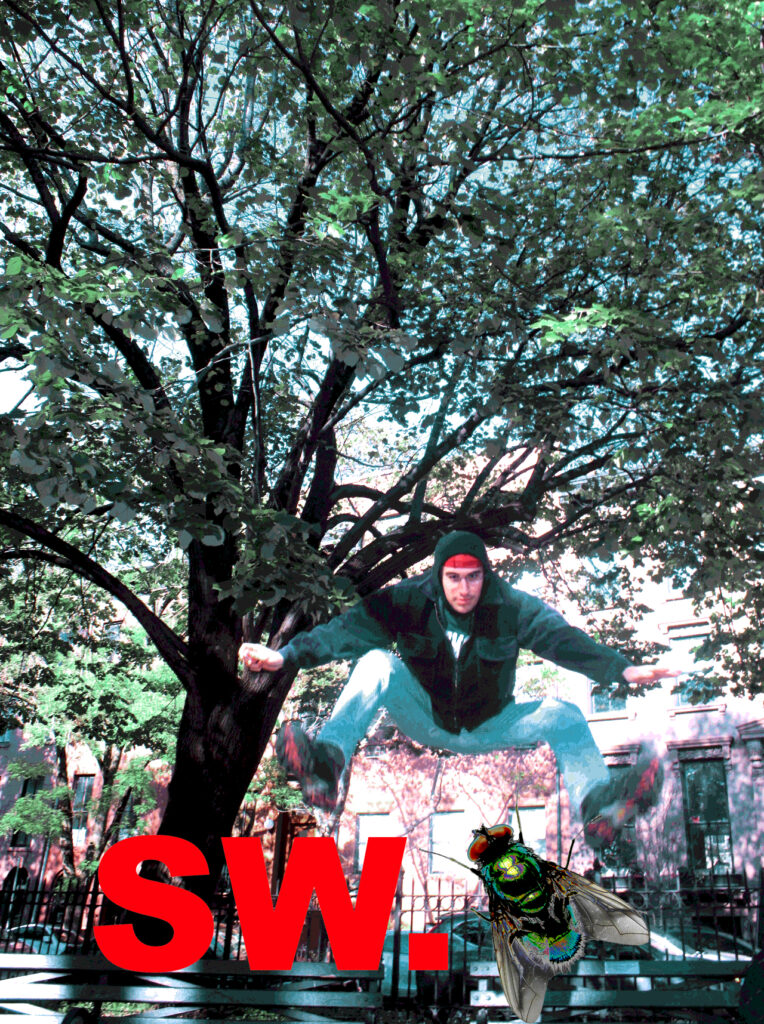

One of the first uploads you’ll find on Claro’s Vimeo channel—active, like most of his social media accounts, for over a decade (his YouTube channel is the same age as YouTube itself)—is an unconventional, work-in-progress music video set to the skater-slash-musician Genesis Evans’ song “SIMPLE,” from 2022’s 8 SONGS. The term “movie” has always meant something visceral to Claro, but more so at an angle than a focused point. “Movies are tyrannical,” he says, midway through a psychological spiel about what he intends to do with his craft, and whether or not it’s possible. “They have your whole attention, your whole body, your whole eyes, your whole mind. It’s why they fail in comparison to music. There’s no movie that you want to revisit as much as an album. There are a lot of movies that I think are really good, but never want to watch again. Because they’re so boring. But they’re so good—like, I know this is a good, effective movie by cinema and art standards… but I’m not trying to watch this shit again.”

A humble character with sights set on commandeering a tyrannical medium, Claro’s options lean, by nature, more towards the atypical. So, when he consults his near-fossil Vimeo account to show me one of his most recent movie-making attempts, it’s understandable that the unfinished music video he cues up turns out to be, instead, more of an intimate slideshow. Inspired by the pivotal 1962 French sci-fi film La Jetée, its nuances are poetic: as Evans croons through simplistic platitudes buoyed by stripped-down instrumentals, on-screen, there’s an equally-simplistic series of photographs documenting the singer’s mundane daily goings-on, all captured by Claro over the course of a day. The brief segment he plays for me sees Evans, among other menial tasks, brush his teeth with bright sunlight illuminating his Urkel frames, go for a morning laundry run in a near-empty laundromat, and stare down a golden-hour sunset through coin-operated viewing binoculars. “You can make a movie without having to be responsible for the seconds in-between,” Claro says, Evans’ auto-tuned voice blaring through his phone speaker. “You fill all that in yourself.”

Another thing you have to fill in yourself is time—this, perhaps more than anything else, being something Claro is well aware of. It’s barely noon here in Brooklyn, but the way seasons work, take away the time, and you’d guess that the sun is setting. Seasonal changes are something Claro’s photography practice has caused him, over the years and even more so post-Italy, to register on a cerebral scale. “It was just the past fall and being back from Italy that kind of taught me that lesson, because I spent my money on that trip,” he says of his steepened need to avoid familiar creative roadblocks. “And it was me being fully ready, and knowing exactly how to do what I had to do, and having no money. Also with the seasons changing, and the anxiety of time: if this whole thing is born out of anxiety—pure fear of death—then that’s probably how it’s going to be. You know what I’m saying? I don’t have time to obsess over a lens, because I might die.”

Though he admits that he isn’t necessarily there yet for now, Claro is vocal about being more on the precipice of a creative rebirth than a creative coda. With this past fall having been reserved for building a financial cushion, by the time the weather gets warm, if all goes to plan, he should be in ample shape to fund the narrativized, intentional, self-directed movie-making endeavor he’s long had the inspiration to pursue, but rarely had the attention span or bandwidth to actualize. The process is already in motion. When I met with Claro in his apartment this past August, for one, he spoke briefly about a photo series he had been planning in conjunction with Louis Osmosis, a Brooklyn-based sculptor and close friend of his, centered on abandoned signs whose long-term exposure to the Sun has resulted in eerie, faded blue color schemes. In the photos he’s taken upon his return, too, hints at cohesive narratives steadily peek through the cracks—in one haunting triptych he captured this fall, there are two close-up portraits of crimson autumn leaves, followed by an otherwise-monochrome graveyard covered in them. Like the dead pigeon, the leaves on the headstones, and the humans six feet beneath them, time runs out for everyone—and while Claro toes the line between incidentalism and intention, his filmmaking harps just as much on the spending of it as its aftermath.

The first time I met Claro in person, he was holed up in his apartment on a July Tuesday, and the primary strain of time on his mind was the short, days-long period remaining before he would board his flight to Italy. Documenting a documentor, especially if that documentor is a Drake fan, is difficult—before you can manage to get any information about themselves out, they’ll either ask you about yourself first, or start talking about Honestly, Nevermind—but after about an hour of stalemate, seated on a couch adjacent to his iMac, he opened up about the looming existential burdens of his practice, and how urgently they needed to be lifted. “The line between something I’m stumbling upon and something I’ve produced—where that ends, and the other begins—is kind of what I’m looking for,” he mused, with a pensive look that felt as if he was on the cusp of a smile never to come. “And up until this point, as you can imagine, just shooting in an incidental manner has been a really slow, deliberate and volumetric process. Everything you’ve seen me put out has been the result of Enough time has passed, and I’ve taken enough photos, so eventually one is going to be interesting. But I want to not die before I make something, you know?” He laughed: “If you look at these binders full of negatives,” he said, gesturing towards a hefty stack sitting on a nearby table, “you’ll see the fear of death in me. Because I have to incessantly capture—as much as I hate that term—some sort of authenticity.”

“You can make people feel alienated if you want to. But I think every step of the way, it’s important to give people something they can feel.”

Much of the authenticity Claro captures in film form is silent. Last year, he co-produced a short film, A Light On the Dash, October Forever, alongside Christopher Currence, Ali Zaman, and his partner, artist Aniza-Imán Íñiguez. In complete silence, save for sighs, failing engines and wistful piano arpeggiations, the narrative sees an ill-fortuned MTA worker navigate a broken car, a not-so-promising visit to a mechanic, and a series of childhood-reminiscent cues en route to a brief moment of elusive hope in his front seat. It operates much like the rest of Claro’s work, across mediums: the clear-cut meaning, if it even exists, isn’t going to jump out at you—and it probably didn’t for its maker, either—but the disparate elements that comprise it are there for the piecing together. If connecting the loosely-correlated dots of Claro’s works shares anything in common with lugging a 300-pound scanner up the staircases of moms’ houses, it’s that both are best done with company, regardless of how well each component knows the next.

When Claro was in Italy, he told me over email that he had been listening to “Crickets at night and lots of repeated Italian phraseology.” Today, leaned up against the outside window of a nearby coffee shop, he reports that his recent listening has been more comprised of the artist Nala Sinephro—more specifically, “Space 1,” from her well-received 2021 debut LP “Space 1.8.” The song sounds exactly like its title might suggest: over a consistent backing of floating keys, spatial audio cues range from distant chirps, rustling leaves, and what may or may not be the far-out pitter-patter of intermittent drizzles. A visit to his low-key Spotify profile—where, as of right now, his recently played artists are an eclectic mix of hyper-successful trap acts and obscure shoegaze bands who seem to make music specifically for fall—raises questions about how, and under what circumstances, certain tastes are allowed to coexist. But for Claro, as is the case with every other thing he puts his hand to, you quickly realize that the more will always be the merrier. “There is the option to just cool-guy everybody, and be like You wouldn’t get it,” he says. “You can make people feel alienated if you want to. But I think every step of the way, it’s important to give people something they can feel.”

One reply on “Incidental Intentions with Devlyn Claro”

you know it’s a good interview when it not only allows you to better appreciate an artist’s work, but also the medium they work in. nice job sammy’s world