Content rules until someone else does. Who will it be?

THEO MERANZE

I was originally going to write this piece on the importance that Andrew Callaghan and his Channel 5 crew’s paradoxical, sacred nihilism once held to a fitting generation — fitting, that is, because it brought with it a history of violation at the hands of media institutions, and appeared to finally have a savior. But then, perhaps just as fittingly, that orphaned generation was let down again. Recently, Callaghan was revealed to have a long, winding history of sexual misconduct, which I do not have the authority, nor the energy to describe, but can be conveniently learned about in great detail in the places on the internet where one learns about those sorts of things (everywhere).

Callaghan recently uploaded a short apology to his Youtube channel, and though it is up to the victims of his behavior to assess its validity, it is clear that he will be relinquishing his role, potentially forever, as savior to the counter-cultural space he once occupied. That space, one that weighs its existence as in opposition to the oft-hegemonic, oft-authoritarian, oft-dehumanizing, and oft-violent business of media, is now more vacant than ever, and perhaps more important than ever, too. While I do not know who or what will take his spot as this generation’s alternative media messiah, I know that it must, and will, be filled.

The question, of course, becomes: by who? And by what means? I do not have these answers, but what I do have is the context within which that person, group, or movement will be attempting to operate: a context dominated by a crushing paradigm that has created a new, ever-evolving, media tyrant called “content.” In the court of the content king, the mind, and all of its complexities, is transformed into a castrated, pleasure-addicted voyeur. We see the repercussions of this transformation in the realm of news (where Callaghan predominantly resided), in the arts, in “influencer culture,” and perhaps most terrifyingly, in our own addiction to it.

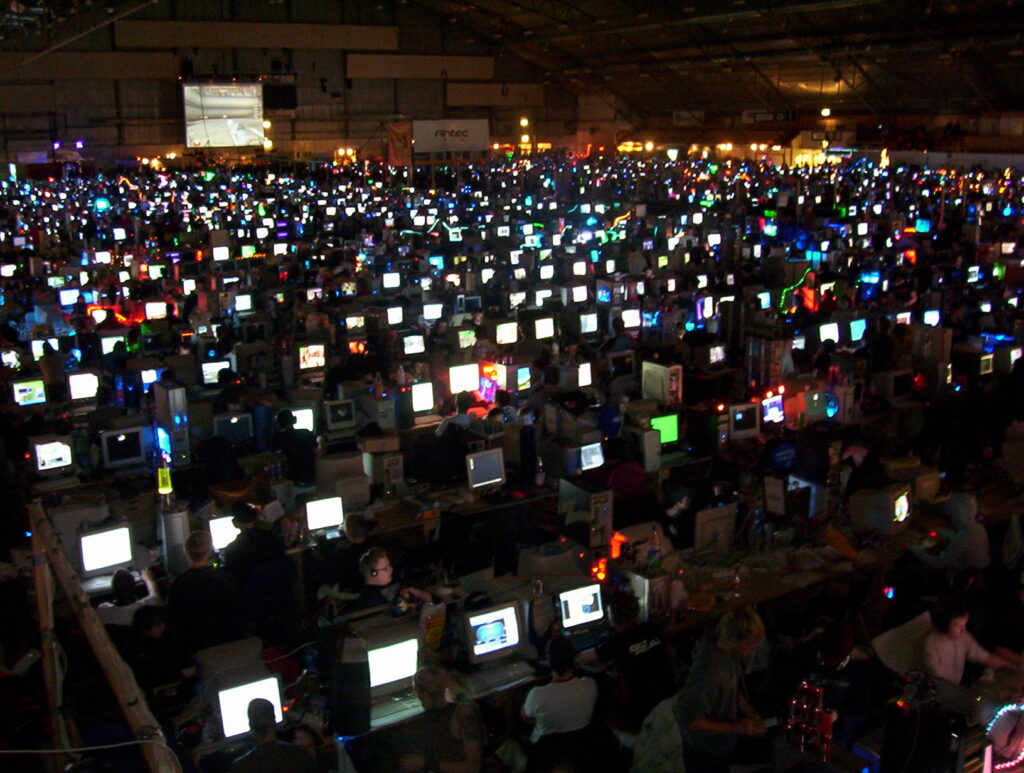

Writing, in all of its glorious impotence, will never compete with the image in the eyes of a generation born to the command of the smartphone and its carnival of stimuli. The late-capitalist code of domination in the name of consumption (and vice versa) has taken new form with the advent of technologies meant to colonize and control users’ perhaps most important asset: their attention. The feeds of Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, and Twitter, through their endless barrages of images and quick-to-digest digital artifacts (short-form posts, memes, videos, infographics) have begun to sculpt a new kind of political and social psyche through a carefully cultivated, addictive conditioning/enchantment. Such a spell is not cast upon the eye, but rather drawn out of its natural impulse to give attention to what is brightest—the aforementioned short-form posts, videos, memes, and infographics—with particular emphasis on those that tug at our most visceral impulses: anger, horniness, excitement, fear. The written word, while beautiful in its purity, is not very visceral, nor is it particularly entertaining, no matter how necessary it may be. In this dissonance one can see the beginnings of the current paradigm burning through our synapses, embodied by a single word familiar to all with aspirations to join what has become of the culture industry: content.

“Content” exists at the confluence of two related contemporary appetites: the capitalist impulse to maintain the rate of production, and our ever-developing dependence upon overstimulation. Through its constant self production, it satisfies both.

“Content” as ideology is an authoritarian, cultural, capitalistic extension of our ever-developing dependence upon technology. Its form of being is not always necessarily political, but its existence is an underlying political reality in itself. “Content” exists at the confluence of two related contemporary appetites: the capitalist impulse to maintain the rate of production, and our ever-developing dependence upon overstimulation. Through its constant self production, it satisfies both. The pursuit of content entails the dehumanization of the populace at large. It necessarily must, as the content machine relies on the usurpation of the unconscious, habitual behaviors of the human psyche. The primary subject of this dehumanization in the realm of media is not necessarily those documented by the camera lens, but the viewer.

The viewer’s perspective, through its cyclical, co-dependent relationship to the content paradigm itself, is mechanized and programmed through the clutches of this new form of media orthodoxy. While this is true in all political or a-political realms of “content” creation (my current addiction to watching culinary Instagram reels is evidence of this enough), in public discourse, its socio-political effects have been most focused on in the realm of news—an industry our twisted connection to unearths strange truths about mass society in our era. The material world and its ongoings must always sit with the heaviness of nuance. But the public’s perspective, with the help of new-form media, can revel in the illusion of simplicity. Such an illusion tends to eventually live in the mind as pleasure. Thus, we can view the contemporary content paradigm as a novel development of the American masturbatory urge to gawk at suffering.

It is no new concept to anyone who has lived through the last decade, however, that the news is trying to “divide us,” that echo-chambers are a problem, or that through our social media feeds we are watching ourselves spiral into something deeply terrifying. More timely, perhaps, is a look into another realm in which this voyeuristic, content-driven impulse has found itself dangerously replicated: Boonk-Gang.

In the culture industry, the content paradigm has tasked creatives and influencers with the consistent upkeep and production of public profiles. Their public-facing posts, actions, sufferings, and likenesses have become as important, if not more so, than the art that they put into the world. In particularly potent cases, like Tay-K’s arrest and Ye’s downward spiral, the latter collapses into the former, and vice versa. Much like it does in the context of news media, the content paradigm spawns itself through the transformation of their perpetual becoming (and whenever possible, suffering) into commodifiable entertainment.

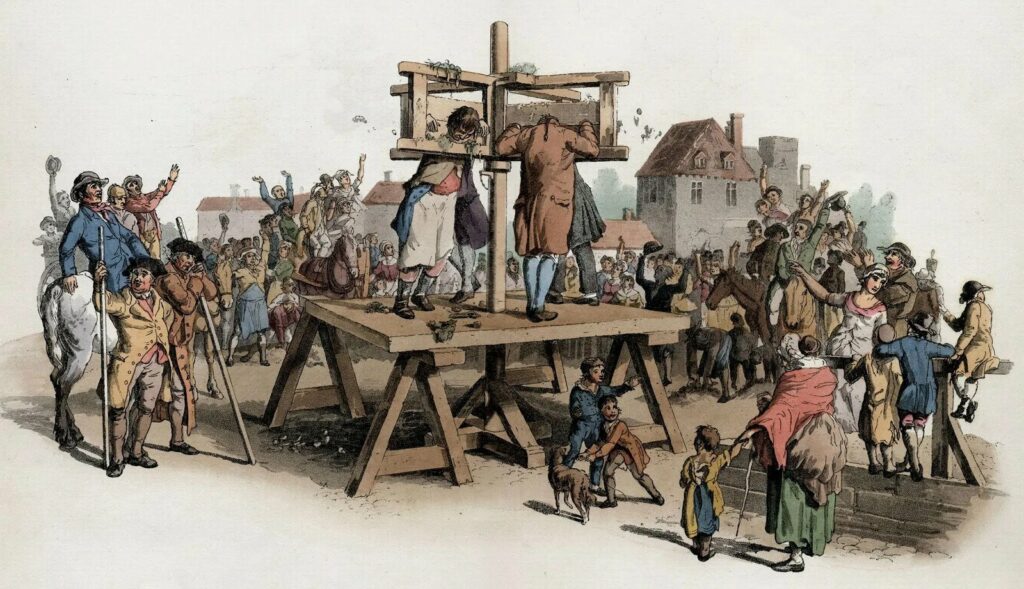

Internet personalities such as John Gabanna, formerly known as Boonk Gang—who garnered a large following through clips of him stealing shit, screaming in public, and generally being a force of chaos—hold a particularly revelatory position in relation to our media state. Personalities like Gabanna’s former self function as messianic harbingers of what is to come, and its twisted relationship to what has been: unlike the news pundit, they are not tasked with cloaking the underlying reality of their mission to transform chaos into entertainment. The influencer’s vocation is entirely founded upon the laying bare of the content paradigm’s underlying premises: a tradition of public humiliation and catharsis.

“In the content paradigm, the line between punishment and performance is continually blurred. In the pursuit of “content,” self-stockading becomes a prerequisite.”

The Western obsession with public humiliation and catharsis is a long one that I do not have the time or space to address here. By no means is it an untouched topic, but it is important to mention, as it is integral to the psychological formations that made and continue to make personalities like Gabbana famous and shape our media landscape. Through his “content,” Gabbana seemed to play with and subconsciously tap into the dark, underlying urges of a public obsessively enchanted with the voyeuristic catharsis of watching a walking car-crash. I use the term voyeuristic intentionally: the contemporary public is not composed of passive, self interested bystanders. Such viewership has its roots in enjoyment, active participation tethered by a just-as-active search for pleasure.

Gabbana was very aware of his fetishization. He has since admitted that many of his videos were staged or at the very least pseudo-arranged, indicating that he was aware that in order to garner fame, he needed to channel the public’s near religious obsession with chaos as spectacle. Unlike the case of news media, the site of organized spectacle was not a narrative of political ongoings, but Gabbana’s ongoing self-flagellation, his ongoing humiliation.

Public humiliation, of course, is not a novel phenomenon. There are infinite methods of public humiliation and torture to be accounted for throughout human history—specifically throughout the history of the West—though one particular instance I find representative of our current condition is the “Stockade.” It was common for Puritans to employ the Stockade (pictured above), to keep prisoners in the village square as townspeople taunted, laughed at, or even assaulted them. Gabbana and the many influencers like him are put in quite a similar position: vulnerable, humiliated, and the object of public entertainment. A disturbing difference is that in the content paradigm, such a “stockading” is not perceived to be oppressive or punitive. Rather, it is incentivized, until it is eventually self-inflicted. In the content paradigm, the line between punishment and performance is continually blurred. In the pursuit of “content,” self-stockading becomes a prerequisite.

The content creator, whether engaging in as absurd a form of attention-seeking as Gabbana or not, believes that they must, and implicitly then want to, commodify, humiliate, or perform their lives for financial and social gain. Unlike other entertainers, such performance is not bound to a stage, a recording studio, nor a film set. Online self-stockading is a constant, all encompassing endeavor. It is a major sacrifice, and one that often does not pay off as planned. In a 2022 Shade Room interview, Gabbana stated, in retrospect, that he “thought that if I could get famous, I could get rich.” He was not entirely wrong: becoming a social media influencer does have the ability to be lucrative, though not nearly as frequently as people think, especially for people of color. “People were scared to work with a kind of guy like me.”

“This emptiness is not the emptiness spoken of in Mahayana Buddhist sutras, an emptiness with the texture of silk that evokes an unspoken sacrality, but rather a banal emptiness with the texture of metal, a sign of our ever encroaching machination—the flaking skin of a machine.”

While influencers in general do not tend to make as much money as we may think they do, the underlying racial dynamics present in Gabbana’s situation and subsequent shunning must not go ignored. One wonders: if Gabbana had not been Black, would he have been more accepted into the fold of the culture industry? Would he have been subjected to his fame and subsequent humiliation in the same way—which is to question if he would have even gone viral at all? Would the conditions that caused him to chase the illusions of a profitable internet celebrity have set him on his path in the first place? We know the answers to all of these questions, and they each point to a fundamental reality of the content paradigm: the commodification of racialized suffering and being as an extension of the white-supremacist context that birthed it.

Those of us who inhabit the current Western, late capitalist context are forced to navigate the hollowness of empty time, of an empty life. This emptiness is not the emptiness spoken of in Mahayana Buddhist sutras, an emptiness with the texture of silk that evokes an unspoken sacrality, but rather a banal emptiness with the texture of metal, a sign of our ever encroaching machination—the flaking skin of a machine. It is a depressed, voyeuristic nihilism founded upon a society addicted to escaping its underlying spiritual dishevelment through catharsis. In the face of this meaninglessness comes the false prophet of the culture industry: content, and all of its discontents, fills up the unconscious void. Gabbana and the News are both prime examples, and prime victims.

Empty of a cohesive existential framework for reality other than the urge to produce and consume, it seems that the social body has fallen into the clutches of this alluring addiction to witnessing its own decomposition. It is this urgent reality that made Andrew Callaghan’s transgressive work so exciting, and his disappointment so painful for so many. Still, what remains clear is that something must change. Though whatever comes next must, in the same way as Callaghan, find an impossibly transcendent middle ground: a mode of content creation that usurps the content paradigm. “Content” that either participates in the critique of itself, or escapes its own hegemony in its totality. What is at stake in this endeavor is the potential for critique, the potential for counter-culture in the digital age. This is in many ways an impossible undertaking, yet it must be pursued—there is no other option.

🌎Theo Meranze is a writer from Los Angeles. He can be found at [email protected].🌎