How Innovations in Recorded Music Low-Key Made Patience Obsolete

Unpacking the decades-long invention process that somehow made two years an oppressively long time to wait for new music.

SAMUEL HYLAND

This past Christmas, the most notable gift I received came in a bulky cardboard Amazon box. Upon cutting open the masking tape on its flaps to reveal what looked to be a travel-friendly briefcase (“thanks mom and dad!”), I flashed my most convincing fake smile and hoisted the mystery object up to my father’s cell phone camera.

“Open it!” my parents then shouted.

Puzzled as to why I would be boasting the empty contents of what was quite obviously a carry-on item, I unlatched the bronze lock mechanism on its front, first showing the camera, then taking a look inside myself. It was a portable record player. The offsettingly skinny, square box that came next in line underneath the Christmas tree was Michael Jackson’s Thriller.

Some thirty minutes later, when all gift-unwrapping was finished for the day and my father showed me the reins of turntable-mastery in our living room, it was a shock to even me how noticeably excited I grew by the minute – emphasis on noticeably. I am notorious in my family for being stone-faced and humorless more often than not. Today, I was convulsing. Jittering. Ululating. Breathing through my mouth. Recording on my phone. Hyped.

Yet, when the needle finally dropped, and a grainy, bass-void, voicemail-esque rendition of Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’ began to emanate from two square speakers on either side of the “briefcase”’s anterior, a gut-punch sensation of letdown quickly settled in. Although I was all smiles for my parents’ cell phone cameras, the first thought to cross my mind upon retreating to my bedroom was a reasonable price for re-sale on eBay.

Don’t delete your Spotify. But don’t get rid of that old record player either.

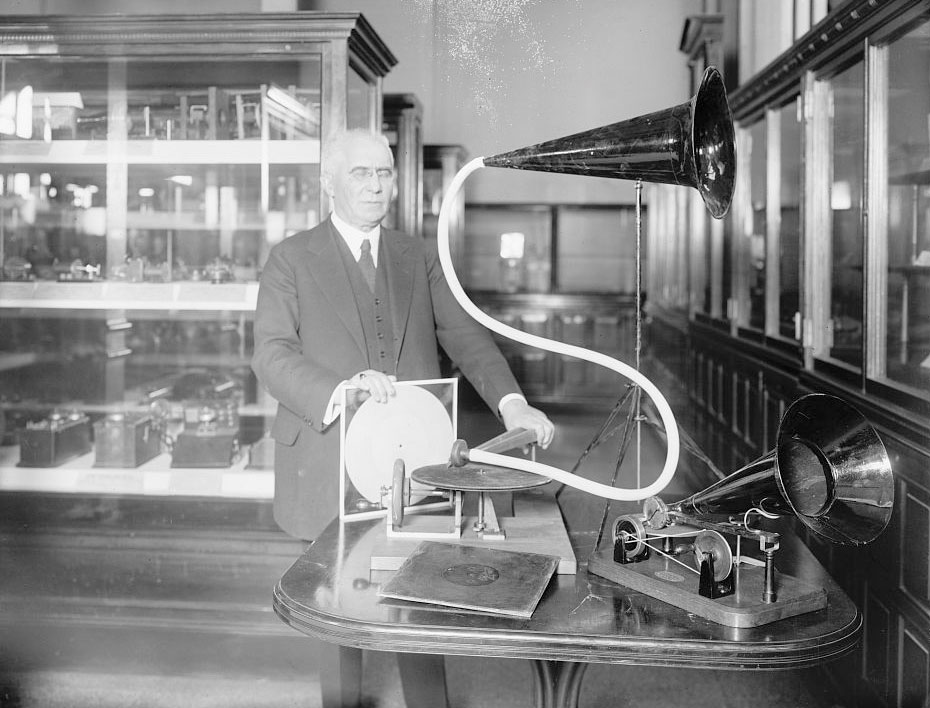

A big part of my disappointment that morning can be traced to the fact that just ten hours earlier, I had stayed up until midnight blasting all 63 bottom-heavy, floor-shaking, trap-punk-marrying minutes of Playboi Carti’s hotly anticipated second studio album Whole Lotta Red on maximum volume. Per the New York Times, around 126 million eager listeners did the same via streaming services. Such figures can be traced to a long-gone shift in the music industry towards technological developments, mirroring similar patterns adopted across the world surrounding it. In the day of my grandmother – who owns a vast collection of over 100 vinyl records, including Thriller – record players like mine and gramophones were the widely accepted primary means of listening to lengthy releases. Today, following decades where advancements like CDs and PDPs made music freshly portable, streaming services have crystallized such futurism by making entire discographies ready at the tap of a screen. As it currently stands, vinyls and gramophones are more steadily marketed for their vibes (touche, Urban Outfitters) than whatever metrics measure their capabilities in playing vast amounts of music efficiently.

The first vinyl-adjacent playback agent was invented by RCA Records (then RCA Victor) in 1931, boasting 33 1/3 rotations per minute, with ten minutes of music stored on either side of the average disc. Although RCA’s versions would wind up selling poorly due to the Great Depression, direct competitor Columbia Records, after a decade of experimenting with similar vinyl technology, introduced a much more highly sought-after variant of the 12’’ 33 1/3 microgroove record – the oft-cited root of the “LP” (Long Play) – effectively inciting a stiff rivalry between the labels. When RCA fired back with the development of a 7”/45 rpm Extended Play disc (EP), a period between 1948-1950 in which both formats battled for dominance (dubbed “the War of the Speeds”) saw Columbia’s LP discs take the crown for housing full-length records, with RCA’s EP discs being used more predominantly for singles.

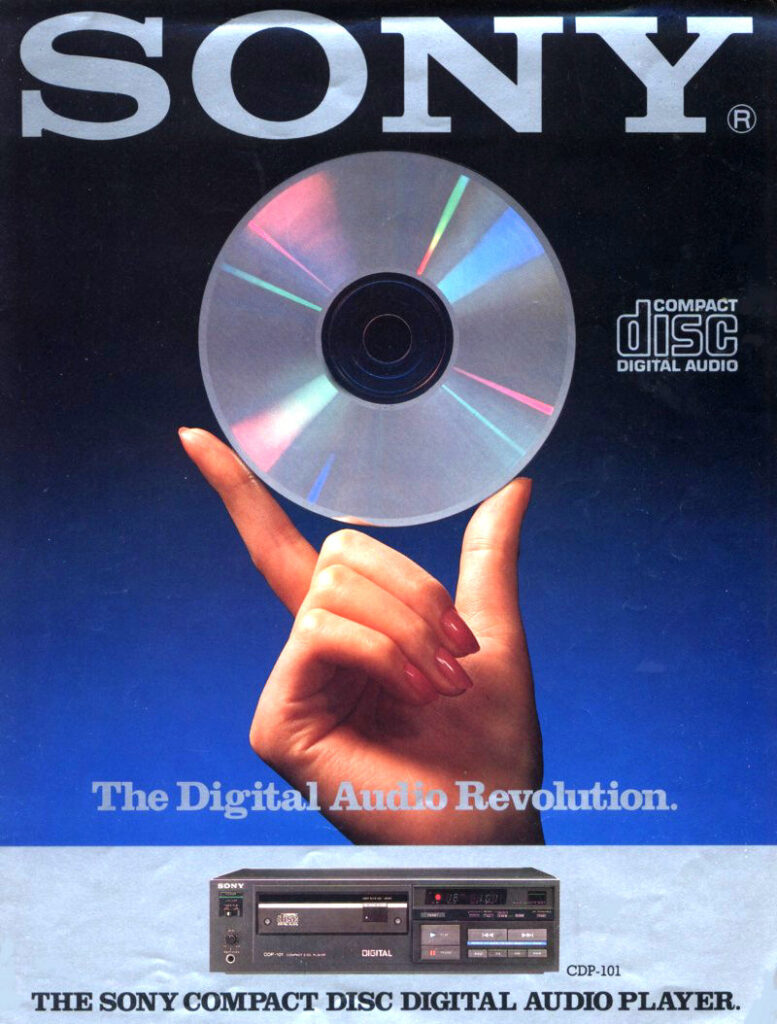

Compact Discs (CDs), on the other hand, were initially invented by James Russell for computing machines a decade after the War of the Speeds, but grew commonplace for storing recorded music beginning in 1982. Following the first CD album drop – a re-release of the Billy Joel album 52nd Street that sold 7 million copies – about 50 albums were released via compact disc overseas, eventually flooding into an avalanche of American emulations including Pink Floyd’s Wish You Were Here, Barbara Streisand’s Guilty, and Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall. The collective childhood of my generation – the one actively pushing vinyls further into the bedroom corner and Spotify further into the charts – is one comprised mainly of CDs utilized in their most efficient forms: whether played via Portable Disc Players, vehicle stereo systems, or work laptops, the Compact Disc epitomized a slow-but-sure transitional period, through which the music business would evolve from granter of household ambiences to concrete cultural cornerstone. Many of those who stayed up until midnight to listen to Whole Lotta Red via Apple Music, Soundcloud, or Spotify on Christmas represent what can only be imagined as the end of that string.

Whereas the focal selling point of streaming services is accessibility, a great deal of what made the rapidly depreciating prospect of physical music desirable was an unspoken layer of intimacy carried within it. In a 1977 Creem essay that was the namesake for his later book Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung, the late rock critic Lester Bangs outlined this in one of many digressions from a point about the Yardbirds: “The real story is rushing home to hear the apocalypse erupt,” he started, “falling through the front door and slashing open the plastic sealing ‘for your protection,’ taking the record out — ah, lookit them grooves, all jet black without a smudge yet, shiny and new and so fucking pristine, then the color of the label, does it glow with auras that’ll make subtle comment on the sounds coming out, or is it just a flat utilitarian monochromatic surface, like a schoolhouse wall (. . .)? And finally you get to put the record on the turntable, it spins in limbo a perfect second, followed by the moment of truth, needle into groove, and finally sound.”

The vinyl record represented an era in music during which its consumption was predicated upon tangibility. Artists emerging in local scenes made names for themselves by consistently purporting to be over-the-top live acts. When those same artists went on wax, whether their records themselves were of quality or not, the music was not often played for the sake of listening alone, but for the purpose of providing animation for house dinners and festive gatherings — the energy they brought to the theater was engineered to translate directly into the ballroom. Given that jazz bands and jazz-adjacent acts made up a vast majority of the musical mainstream, too, a severe lack of diversity in music made tangible elements of physically purchasing, playing, or merely owning vinyl records that much more fundamental within an infrastructure that could have quickly proven monotonous.

“What happens when the kid has already gotten his fix, but is left no way to leave the market?

The intimacy afforded to consumers through physical records, up to this day, is just as present at the producer standpoint. This past summer, New York Times music critic Jon Caramanica met with Rory Ferreira, a Nashville-based recording artist who makes avant-garde hip-hop under the moniker R.A.P. Ferreira; the rapper was in the process of packing vinyl orders for shipment to waiting fans. While Ferreira himself swiftly faced backlash from followers unwilling to pay a hefty price tag – $77 for a vinyl version of his newest double LP – Caramanica cited the efforts of late Los Angeles hip-hop staple Nipsey Hussle as an epitome of both what vinyl has become, and how its new ethos is best utilized. With the release of his 2013 album Crenshaw, Hussle set aside a limited collection of 1,000 vinyl versions made available for $100 each, advertised heavily by a campaign dubbed “Proud2Pay.” The campaign functioned as a de facto loyalty gauge for his fan base – do you support me enough to drop a Benjamin on my tape? All 1,000 records sold out. “Hussle understood that the physical album was no longer a music delivery system, but a proxy for fan enthusiasm, a merch totem of its own,” Caramanica concluded. “This was an especially key development in an era when physical sales were in decline and streaming services with their own economic interests were on the verge of inserting themselves as crucial middlemen between artists and fans.”

Streaming services, on the other hand, represent the pulling of music into what thousands of grandparents nationwide have labeled a descent into American “microwave society.” With Netflix widely pioneering the concept of broadcasting entertainment via the internet, Spotify quickly followed suit with music, launching in Europe a year after Netflix’s founding in 2007, then quickly taking over the United States throughout the 2010s.

The first time I heard of a musical album of any sort, my sister and I had been debating in the backseat of my uncle’s car as to whether “albums” could be of things besides pictures. In a heartbeat, my uncle turned around, rummaging through the center console, then hoisting up a thick CD envelope of Kanye West’s Graduation. “This is an album,” he proclaimed. In contrast, the very first time I attempted to listen to an LP, I sat in my living room couch, fiddling with the green SHUFFLE PLAY button above Daft Punk’s Random Access Memories on an illegally downloaded premium version of Spotify. With my uncle’s Graduation CD came posters, illustrations, a pack of pamphlets bearing song lyrics, and the tangibility of a product one could physically hold. With my Random Access Memories download, any level of intimacy was completely stripped away.

Given the fact that my first attempts to listen to albums were thwarted by empty pockets in posh record stores – not to mention the complete lack of anything to put a CD or Vinyl into – yes, using Spotify afforded me the luxury of hearing whatever I wanted to hear, whenever I wanted to hear it, however many times I wanted to repeat the process. But over the piles and piles of album streams that have passed between me first stumbling upon the app, and present day – much like anyone else – there have been moments in which I have grown so bored of the grand scope afforded that, no matter how different, all music began to sound the exact same. The age-old saying posits that it is pleasurable to be a “kid in a candy store.” But what happens when the door is locked? What happens when the kid has already gotten his fix, but is left no way to leave the market?

Yet instead, the opposite has occurred: no, the joy has not been sucked out of music – immediacy has simply taken its place at the forefront. We always needed new music. But when new music became a cell-phone tap away, we needed new music now.

A side-effect additionally attributable to the rise of streaming services is a sense of immediacy that has largely catapulted itself into what is generally expected of the artist. Given that rock music found itself in an American renaissance around the same times that both the vinyl record and the compact disc gained traction, it serves us well to measure the tendencies of its respective fan bases against those of trap devotees mostly reliant on streaming services to examine the issue. The California-centric funk rock band Red Hot Chili Peppers released their eponymous debut album in both CD and Vinyl formats in 1984. In 1991, when their fandom dramatically increased due to the success of their fifth LP Blood Sugar Sex Magik, they sold 7 million copies across both platforms in the United States. Given the sense of urgency having rippled from music’s then-spurting convenience, there was a considerable amount of impatience that populated the three-year wait period before their studio follow-up. And when One Hot Minute – an album marked by the replacement of guitarist John Frusciante by Jane’s Addiction musician Dave Navarro – finally hit storefronts in 1994, frustrations surrounding the lengthy wait having not been worth it raged to a point where band members were mailed angry letters on a regular basis.

An element often cited in such arguments was the music video for Warped, the record’s lead single. Warped itself is a song that strays from the boom-bap sex-funk instrumentalism popularized by the band – rather than that, there are shameless nods to heavy metal packed within blaring guitars, compressed together in intervals with somber acoustics and mellow lyrical content. The music video’s most controversial moment featured two silhouetted members of the band sharing a kiss on the lips. “We did have a huge backlash from the college-frat-boy segment of our audience,” RHCP frontman Anthony Kiedis recalled in his memoir Scar Tissue. “We got letters denouncing us as ‘fags,’ and rumors started spreading, and we started to second-guess our decision.”

As it stands right now, withal, it appears that the band’s fanbase has evolved over time. Faced with the exact same situation they saw decades ago – a brand new guitarist ushering in a polar diversion from musical roots – listeners who waited five years for the sequel of 2006’s Stadium Arcadium filed comparatively few grievances, responding to the apparent new musical direction with welcoming arms seldom offered to Navarro years prior (he was kicked out of the band in 1995). As we speak, fans of the Red Hot Chili Peppers venture into their fifth year of waiting for a new release, tying the longest wait time between albums imposed by the group. Notably, up to November of 2019, a majority of devotees seemed more concerned about a pending autobiography set for publication by bassist Flea (Michael Balzary) than any upcoming music.

To contrast, the album that I, along with about 126 million eager listeners, tapped into early Christmas morning came at the conclusion of a 2-year wait for more music from one of hip-hop’s most enigmatic figures. Playboi Carti released his eponymous debut mixtape to generally favorable reviews in 2017, following it up with 2018’s Die Lit: a bubbling, charismatic, debut full-length that expanded his reach from devoted trap-scene regulars exclusively, to anyone bearing either a functioning radio system or a nose for city nightlife. Whole Lotta Red’s wait period epitomized the culture of Carti’s fanbase so extensively that its Rolling Stone review could not leave it out of sentence number one: “The only certainties in this world are death, taxes, and Playboi Carti fans leaking his songs before he can release them himself,” Danny Schwartz wrote.

Even before Whole Lotta Red, amidst an infrastructure that saw rappers’ songs prematurely released by devoted supporters more and more often, Playboi Carti’s following managed to emerge as poster-boys-and-girls of a phenomenon dubbed “leak culture” by music journalists and social media users alike. As of August 23rd, 2019, even, a Soundcloud playlist surfaced with 125 of his leaked songs, NME reported. (They were just as in on the gambit – the article in question was headlined, verbatim: Mumbling! Baby voices! The song of the summer! It’s the 10 best Playboi Carti Leaks).

Periodically, between mockup versions of Whole Lotta Red’s allegedly scrapped first rendition being taken down from the internet, and new leaks inevitably surfacing on the same exact sites until disciplinary measures were once again enforced, there existed notable periods in which high hopes came crashing down into fireballs of frustration. Cryptic Instagram captions from the rapper – “<48 hours! locked in” perhaps being the most notable – fueled periods in which Carti’s fandom, many perched in his notoriously strange subreddit, went in full-on this-is-not-a-drill mode (remember that Spongebob scene with all the mini-Spongebobs burning papers and going crazy in his brain?), only to return after whatever timetable they had in mind more enraged than they already were. “Carti listen you have disappointed us many times with this album release and we still worship you,” one fan commented on the rapper’s Instagram account in 2020. “We are in fucking quarantine rn. Plz bless us.” Die Lit had been released a mere 21 months prior.

Much like newfound CD-influenced senses of urgency did for One Hot Minute’s reception, the immediacy granted by streaming services also prompted harsh Whole Lotta Red reviews from both fans and skeptics alike. Within a few minutes of the album releasing on worldwide streaming services, one copy-pasted comment appeared numerous times underneath tweets prompting WLR discourse: “Just finished listening to WLR, currently lost for words man, crying real tears carti bro, this is quite possibly, quite literally, sincerely, the worst possible music I have ever heard,” it read. “My ears are dripping with blood, currently on my way to the emergency room on Christmas Day.” Obviously, the reasoning behind the note was more sarcastic than it was literal. The fact that such comments gained thousands of likes, however – more likes than many tweets favoring the project that night – pointed a shining red finger to the manic offense supporters took to any mere inkling of a sign that the album fell short of expectations. No one would accept anything less than a wait time proven worthwhile: two years, compared to the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ five.

If there is anything I learned from a Christmas spent on two completely opposite dimensions of recorded music, it is that when you have an album with standards that lofty – especially following a wait period of merely two years – it is impossible for it to reach what bars are guaranteed to be set. The predicament exists solely because we have allowed urgency to usurp value. Music, at its outset, was chiefly purposed for the joy of whoever harnessed its power – and then, with developments of LPs, EPs, CDs, PDPs, and Streaming Services, the intent was to make such joy more accessible for everyday listeners removed from the luxury of conjuring such a sensation themselves. Yet instead, the opposite has occurred: no, the joy has not been sucked out of music – immediacy has simply taken its place at the forefront. We always needed new music. But when new music became a cell-phone tap away, we needed new music now.

I did not sell my record player on eBay this past Christmas. After letting it collect dust for about a week after it emerged from its cardboard box, I slid my Thriller vinyl out of its socket, placing it carefully onto the centre spindle and dropping my needle onto the outermost jet-black ridge, now in a steady spin. And as a grainy, bass-void, voicemail-esque rendition of Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’ began to emanate from two square speakers on either side of the “briefcase”’s anterior, a gut-punch sensation of infinity quickly settled in.

Don’t delete your Spotify. But don’t get rid of that old record player either.