How Johnny Rotten and Public Image Ltd. Took Things Into Their Own Hands

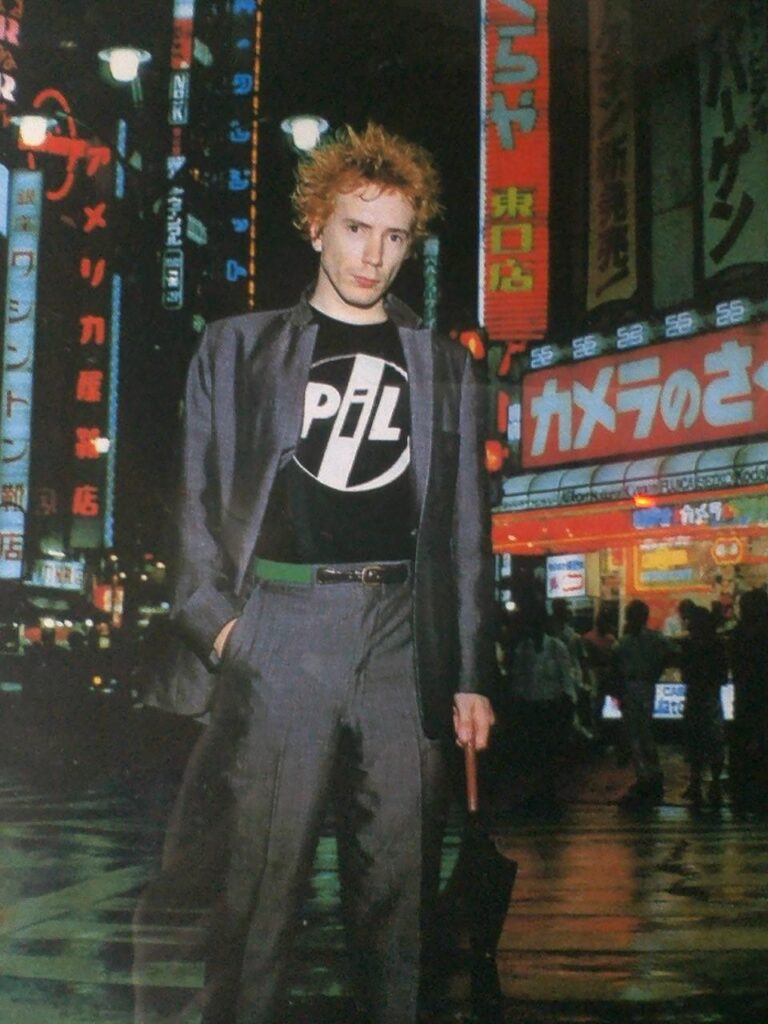

How Public Image Ltd. redefined the rift between artist and audience. (BELOW: Johnny Rotten)

SAMUEL HYLAND

On January 14, 1978, following one of many bloody, drug-infused public meltdowns by bassist Sid Vicious, a flu-stricken John Lydon took front stage at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom to conclude the Sex Pistols’ first U.S tour. The band was falling apart. In the few months that spanned between their magnum opus Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols and their fateful string of final performances, all that could go wrong did: they had been infamously pitted against each other by manager Malcolm McLaren, toxic groupies put members onto near-fatal heroin addictions, and nearly every penny made from a chart-topping debut album slipped through irresponsible fingers en route to virtual destitution.

But today – despite coughing up blood via a terrible mixture of heroin and influenza – Lydon had a capacity crowd of over 5,000 Americans to entertain. And when they wanted an encore, an encore is what he gave them:

“You’ll get one number and one number only, ‘cause I’m a lazy bastard.”

The number promised was a sloppily improvised cover of the Stooges’ No Fun. By the final cymbal crash, amongst various other made-up lyrics, Lydon added: “This is no fun. No fun. This is no fun—at all. No fun,” his familiar sneer and tired eyes purporting that he meant every word.

“Ever get the feeling that you’ve been cheated? Good night.” He threw down the microphone and walked off stage. The Sex Pistols were over.

It’s a story of grave mismanagement that has been regurgitated to the point of folklore, details skewed, exaggerations piled one atop the other, truths buried beneath heaps of shock porn – Yet in spite of it all, the defining question remains intact: What if?

What if Malcolm McLaren hadn’t fucked up so bad? What if we got an encore to Never Mind the Bollocks? Much like the group itself, the general consensus amongst Sex Pistols fans ends in a question mark, not a period.

For the band, on the other hand, the premiere variation of this consensus manifested itself in the form of What’s next – the answer to which, for many members, came to the tune of violent deaths, continued substance abuse, and failures to revisit musical summits reached in the good old days.

But these answers took decades.

Johnny Rotten’s own took six months.

It had been no long period after the Sex Pistols’ implosion that John Lydon got to recording his new band’s debut single Public Image, accompanied by a diverse group of former Clash members and underground part-time instrumentalists alike. Apart, the group was a pack of guitar-strummers disgruntled with tarnished opportunities. But – together – they were Public Image Ltd.: the unofficial arrival of a post-punk brand that danced atop its predecessor’s grave, both middle fingers flailing in midair.

Public Image lends itself as the epitome of such newfound rebellion. With driving percussion and searing strings screaming a jubilant I-don’t-need-you-anymore to years of mismanagement and abuse, John Lydon sounds happy for once. It’s a cosmic shift from the gritty undertones of Never Mind the Bollocks; and, for Lydon (who began writing the song amidst the Sex Pistols’ last days) it’s a new beginning – one inaugurated by a declaration that his public image belongs to him and no other — especially not the Sex Pistols. “They never bothered to listen to what I was fucking singing,” he told Melody Maker of his old group. (the full conversation is included as the last track on the group’s first LP). “They just took me as an image.” Public Image baptizes Lydon’s likeness while holding his past under the water to die.

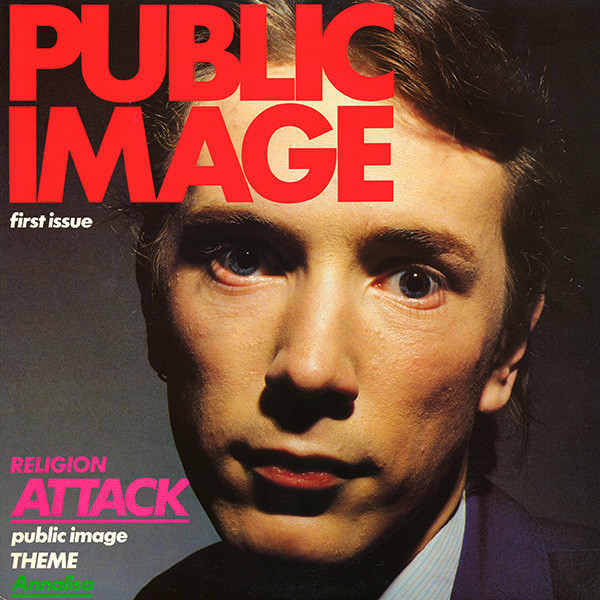

Released five months after its lead single in December 1978, the group’s debut album fully bathes itself in the concept of complete control over one’s own narrative. Most associated artwork revolves around a media-centered motif; its cover looks like that of a magazine, its singles are packaged as newspapers, and the only things keeping it from being eponymous are the words first issue, which, as they would on a tabloid, appear in tiny white letters beneath the larger-than-life publication label. From the sleeve, a robot-esque Lydon offers consumers a grim, mechanical stare, his head tilted slightly to the viewer’s right. In previous years, he was the TV that the world watched. Now, from the screen, he was glaring right back at the audience.

Delivery is what changed about punk’s programming. In the genre’s past, gloomy messages were encased within gloomy melodies, angry tirades were wrapped in angry guitar licks, high-powered lifestyles were represented by high-powered tempos. With Public Image Ltd., the same whirlwind of emotion came with music that signified its conceptual opposite: happiness, all things good, lust for life.

In Annalisa, the classic bass guitar/kick drum rhythm section popularized by funk and soul genres opens the first two bars. It’s on some Parliament-Funkadelic shit; it’s upbeat, it’s flavorful. But, as for the song itself – from the mouth of its writer: “It’s about these silly fucking parents of this girl who believed she was possessed by the devil, so they starved her to death.”

Attack, moreover, one of the shorter songs on the album, is carried by the kind of percussion-driven barrage that leaves the body no option but to move, even if that movement is not necessarily dancing. Guitar blankets all two minutes like colorful UFO discharge, and the environment created by the band is one of an alien invasion pulled from a 1950s television screen. The lyrics, however, tell a different tale. The word attack is repeated twenty-nine times between countless threats of consequences; there are violent callouts of indoctrination and ruthless slanderings of prideful cocktail glass-tinkerers throughout.

The ability to tell two stories at once was the difference between punk rock and its Public Image Ltd.-birthed post-punk successor. The past of punk was marred by a single reputation of thuggish vulgarity; yet, with 1978, the same aura was smushed together with an optimism that once seemed to have no place alongside the latter. Now, punk could be played with reverb. Punk could be played with harmony. Punk could be played without leather jackets or frizzy hair or dusty black boots. It wasn’t about the image anymore, it was about the culture – and the only prerequisite for playing punk was being one at heart.

That was the crux of Johnny Rotten. It was there when he left the Sex Pistols, it was there when he named Public Image Ltd., it was there when he took to the studio for work on Public Image: the once-impossible feat of being in full control of one’s own perception beneath the bright lights.

The Sex Pistols days represented the first side of John Lydon’s story, one of abuse from drugs, management, and the public. His perception was nowhere near his own control. In the weeks that followed the breakup, now-condemned manager Malcolm McLaren went as far as to claim the ‘Johnny Rotten’ moniker that he’d popularized as a member of the group. Lydon’s gelled hair and inner city style became unwanted, widely imitated trademarks for the punk wave over time. The consumer was happy. The producer was a suicidal heroin addict.

But with time, the TV decided to watch the audience. And the audience had no choice but to stare at its reflection, ponder leaving the living room, and uneasily resolve to remain ensnared within this new, initially awkward interaction called post-punk.

On January 14, 1978. A capacity crowd at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom demanded that the TV provide an encore.

The TV looked them in the face and said: “You ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated? Good night.”