The Humble Honesty of Genesis Evans

Genesis Evans is taking life one realized project at a time.

🌎 🌎 🌎

SAMUEL HYLAND

Somewhere inside the black of a TV screen playing one of Kanye West’s many mid-Yeezus tour spiels, the hazy reflection of Genesis Evans is lighting a joint. It’s a little bit after 10 AM in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, and as the morning sun creeps in through a nearby window, Evans is excitedly running me through the genius of Kanye’s philosophy amidst a cloud of skinny smoke swirls. As of right now, the specific YouTube video we’re stuck on is a thirteen-minute fan-recorded clip of a masked West, autotuned, belligerent, and undoubtedly right, addressing his raucous hometown Chicago crowd about why “We should have never ever let Michael Jordan play for the Wizards.” The stream of consciousness, half-rant and half-sermon, follows a line of logic a little bit like this: Michael Jordan made the Bulls organization (and the whole NBA, when you think about it) what it was. When, upon retiring, he went to the front office to inquire about owning a stake in the team, they laughed him off and told him that all he would ever be was a player. Life wants to tell you that all you can be is a player. It wants you to think that you aren’t capable of owning anything. Why is humility looked at as more honorable than confidence? Why is it more acceptable to diminish yourself than it is to uplift yourself? Kanye West believes in himself. And Kanye West believes in you, too.

Seated next to me on a wooden chair, Evans awards himself the role of makeshift live TV analyst, contextualizing West’s every move and color-commentating every brashly-put declaration. “I feel like Kanye’s always been true to himself,” he says at one point, as the drenched organs of “24” embellish choral chants of “God’s not finished” in the background. “In my life too, I didn’t have any, like, male figures—especially when it comes to talking about what it’s like being black in America, and race and all that shit. (Kanye) was that. He’s an activist. He’s like a musical activist.”

“At one point in time, like a month ago, I wasn’t able to do this; now I’m doing this shit.”

The last time I spoke with Evans in person, we were crammed into a tiny rehearsal space in Brooklyn, and he and his band Blair were running through a selection of songs for their cathartic April EP “Tears to Grow.” It was September of 2020—the height of a legendary Twitter spree that saw West leak important phone numbers, urinate in Grammy trophies, and publicize every single page of his recording contract—and as we made small talk while preparing to exit the venue, West was a bit more of a punchline in conversation than an icon (if you’ve seen that one video of his unnecessarily-large television screen, you probably understand). On this day in particular, yet, Kanye is once again somehow finding himself at the forefront of our dialogue, and now not so much as a quip: Evans is reciting details like a longtime scholar of West’s unorthodox doctrine; I am getting a purging primer on just how much of a cultural weight I never, until now, gave Kanye enough credit for carrying.

Evans’ fixation with West is vested in the fact that, he explains, whereas a majority of other celebrities often sacrifice authenticity for marketability, Kanye is remarkably willing to face the fire if it means telling the truth. In the second of several Yeezus tour stream-of-consciousness videos we watch, for instance, West sarcastically pretends to end the show because he’s “so scared” of what “people on the internet” are going to say, and he wants to remain politically correct for fear of being attacked by mass media. Evans jumps to provide his exegesis: “People don’t realize he’s the most selfless. People think he’s selfish. But it’s not for him; it’s to get these messages across. Just imagine the weight he holds. How scared he actually is. There’s a point behind it. It’s not all just some dickhead move.”

At 25 years of age, Evans himself has come to a place where, much like West, he’s realizing the points, or lack thereof, behind a great deal of what he both actively and no longer does. Evans began skateboarding in middle school as an outlet for at-home frustrations, after being introduced to it by a cousin of his at a family event. He was born to an immigrant mother from Panama, who, having moved to the United States at just seven years old, often translated the rough lessons she learned as a first-generation citizen into her parenthood—when Evans first started skating, because of her protective inclinations (along with bad crowds that were growing fond of local skateparks), he wasn’t allowed to go beyond her line of sight. “At first my mom was scared of me going out to further places,” he tells me, “so I would just skate in front of my house. Then also around the corner, a couple blocks.” As Evans got older and his mother began to trust him more with his own safety, he began venturing to skateparks in places like Park Slope—though at first, his mom insisted that he wear a helmet and stay where she could see him. Quick excursions to local parks soon turned into lengthy forays, some accidental and others not, into different cities (Not even in New York, sometimes: we’re talking Philadelphia). The pains of life were snowballing, but at the same time, so were the joys of skating.

“Just seeing improvements,” Evans says, when I ask what kept him in it early on. “Being like ‘oh I couldn’t do this shit, but I did that shit.’ You know? Like ‘At one point in time, like a month ago, I wasn’t able to do this; now I’m doing this shit.’ It’s very symbolic. It definitely had me looking at myself like I can do anything. No one ever told me that. Skating did that for me.”

“Especially when you think something is so cool, and you’re like, Oh that’s so cool, I wish I could do that. Just do it. Be that person.”

Growing up, Evans shared a room with his brothers, and often had to follow a strict set of rules—no inviting people to the house; no telling people that dad is in prison (Evans’ go-to cover-up story was that his father was on a work trip); no hanging out with the slightest inkling of the wrong crowd. But for as much as the emphasis was more on the contrary of “I can do anything” at home, in high school, the art of doing may well have been impossible. Evans applied to an arts institution in Brooklyn he doesn’t remember the name of, not because he knew his art history in and out, but because he was interested in learning how to creatively express himself. Surrounding him in his Brooklyn apartment, the makings of this creative intuition evidently haven’t gone far: the walls are decked with paintings by both himself and his friends; a stack of books and card games sits atop a piano off in a sunlit corner; the first painting he ever made as a teenager—a dark, cartoonish rodent with a yellow hat and blue two-piece outfit striding in angry esteem—sits feet away from a poster he would go on to make years later with an artistic collaborator for an independent brand.

As far as that art school goes, though, he failed his audition badly (“I was like, ‘damn, so I’m not an artist,’” he says). In lieu of going to his dream art institute, he enrolled in another academy with “art” in the name, hoping that it would fulfill his creative desires. Much to Evans’ dismay, the High School of Telecommunication Arts and Technology was not exactly the artsy haven he thought it would be.

Yet, if being in a boring high school did teach him anything, it was about people: growing up somewhat isolated as a result of his upbringing, Evans played host to a rare, clear-eyed vision of humanity, a survey that posited from the outside looking in, but still wasn’t unable to get in the mix. It was in holding this position that he recognized the most cool people to be the outsiders.

“The kids that would kind of get bullied or who people thought were weird, I always thought were cool,” he says. “Shit like that. Like, ‘you’re cooler than what they are. You actually have a personality.’”

In one story he tells me between laughs, Evans was caught in the middle of a food fight while playing Yu-Gi-Oh! at a lunchroom table. As hordes of students bulrushed the heart of the action, Evans recalls having seen a classmate be inadvertently pushed by security guards into a pillar, causing his head to bleed.

“I was, like, crying,” he says. “Like, ‘someone help him!’ I forget his name, like, Darius or something. I was like ‘Darius! Someone needs to help him!’”

Thankfully, if not given away by the heavy laughter Evans retells the story with, Darius did eventually get help. But in an even wider scope than Yu-Gi-Oh! and busted heads, the story poses an image uncannily reflective of the skater’s character at-large: literally—while everyone in the world could be preoccupied with a food fight, he’s just far enough from the pull of collectivity to be able to notice the guy bleeding in the corner. It’s this sense that gives his iconoclastic approach to creativity, be it fashion, music or skateboarding, a rare humanistic glimmer. He doesn’t do him solely for his benefit; he does it to show you that you, too, are capable of doing the same for yourself. At one point in our interview, for instance, following a question about his fashion sense, he pauses to show me an anime character on his phone.

“I want to be my version of when I see someone and I’m like damn, that person looks cool,” he tells me. “Everyone should be their best version of that. That’s what I’m saying—I want to be my best version of myself. And I feel like everyone should want to be their best version of themself. Especially when you think something is so cool, and you’re like, Oh that’s so cool, I wish I could do that. Just do it. Be that person.”

Genesis Evans believes in himself. And Genesis Evans believes in you, too.

🛹 🛹 🛹

Evans was a great student in high school—he asked insightful questions in class, and his teachers only ever had good things to say about him. But because life at home often kept him from doing his homework, and he didn’t know he had anyone to talk to about it, by senior year, he found himself in a position where if he wanted a shot at graduating, he would have to do at least two more years. The answer was an obvious one for both him, and probably anyone else who’s ever been in his position: “Fuck that!” All the same, his mother’s answer was, too, an obvious one for both her, and probably everyone who’s ever been in her position: “Do you want to be homeless?”

Through the years of skateboarding he already had under his belt, Evans had already developed relationships with several figures associated with Supreme. Upon learning that he was looking for work, they offered him an opening at the company’s LaFayette Street location. It took some convincing to get his mother on board. “I remember telling my mom; she didn’t know what Supreme was,” he laughs. “She was like ‘A skate shop? That’s not even a real job,’ you don’t even know. But then when I quit, she was like ‘why’d you quit?’ Once she figured out, she was like ‘Damn, this shit crazy.’”

Evans worked at Supreme for five years, spanning from the end of his high school career to the early stages of the pandemic. It was, in some ways, a sort of unofficial matriculation period into the inner skate culture he had long danced around in earlier stages—he was surrounded by like-minded people, awestruck young skaters took selfies with him as he rang them up, and, perhaps most importantly, money was consistently coming in rather than going out. His skating had turned his YouTube channel (foghornleghornn – the namesake of his musical moniker) into a folk hero-esque beacon for skateboarding’s up-and-coming generation. As a member of skate companies including Supreme and 917, he was being flown both nationally and internationally to shoot videos and do tours.

“It was this crazy palace that, like, presidents have stayed,” Evans says, before trailing off and briefly toying with the piano in the corner. “Fucking like… there was a photo of one of those old ass presidents.”

One memorable instance that comes up in our chat is of a Supreme skate team trip to Mexico City. After rummaging through a set of cardboard boxes stationed adjacent to the television—now playing Teezo Touchdown music videos on repeat—Evans extracts a mini photo book of the trip published by the photographer Grace Ahlbom. Inside, page-wide captures see Evans in a curbside joint sesh with Sage Elsesser, Sean Pablo playing video games on a lavish bed, and the group sharing dinner over the kind of long table, backgrounded by a larger-than-life mural, that you would see in a film about medieval mansions haunted by the ghosts of kings. “It was this crazy palace that, like, presidents have stayed,” Evans says, before trailing off and briefly toying with the piano in the corner. “Fucking like… there was a photo of one of those old ass presidents.”

Yet when Evans left Supreme, it had nothing to do with any of these factors—anyone could (and would probably really want to) make it in life by skateboarding through Mexico City whilst living in presidential palaces. One day in 2020, he looked up the Wikipedia page of his long-estranged grandfather, the Panamanian jazz musician Carlos Garnett. “I was like damn, Miles Davis!?” he says. “He played with Miles Davis. I was like damn. He moved here just to pursue his dreams.” No more than 24 hours later, Evans quit his job.

The decision is one that has, for as much as it granted a newfound level of creative freedom—even to the capacity he dreamed of as a bright-eyed teenager applying to art school—also made the tightrope thinner. Evans admits that he doesn’t have much time to play games: as we speak, he has a family to take care of, a community to inspire, and a lifestyle to support. The inhibitor he identifies within himself is that he is often too eager to start things and too lazy to finish them. The same way that a look around his apartment gives proof to the persistence of his creative intuition, it also shines the same light on an abundance of unrealized projects: the painting by the piano is just as striking for its beauty as it is for its potential. The piano itself may likely have seen far more music than the public ever will. Humble, the brand for which the aforementioned poster (the one feet away from Evans’ first teenage painting) was made, is on a temporary break because of an industry that thrives on money rather than substance. (“We’ll be back,” he assures me).

Notwithstanding, though, at the end of the day, unlike what was afforded him while working a 9-to-5, Evans has the capacity to value the fun had along the way just as much as, if not more than, concrete success. “All I do with everything I do is figure it out while I’m doing it,” he says at some point, loud Kanye West music competing with his chill intonation on my tape recorder. “That’s just it. And what comes out of it is what comes out of it.”

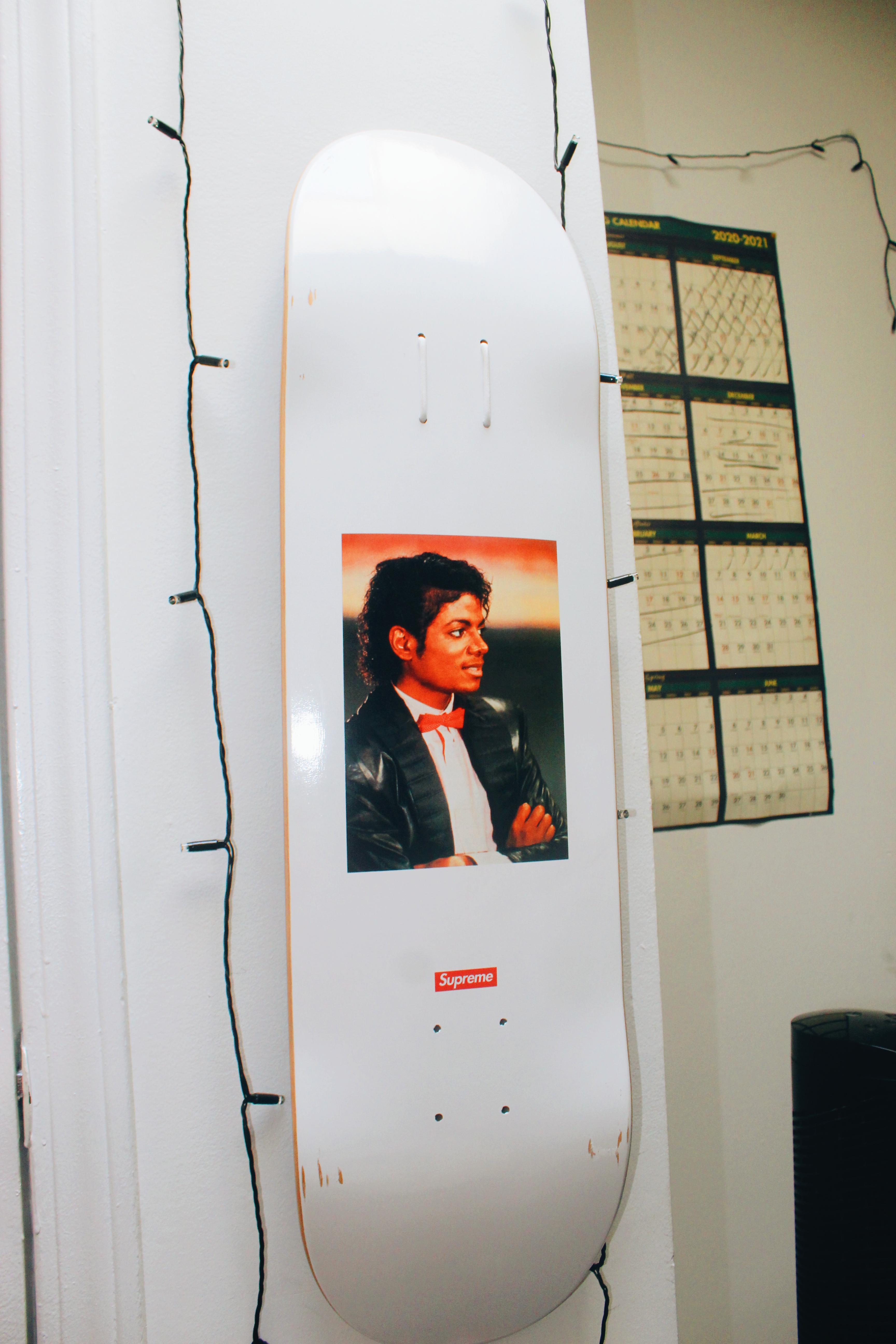

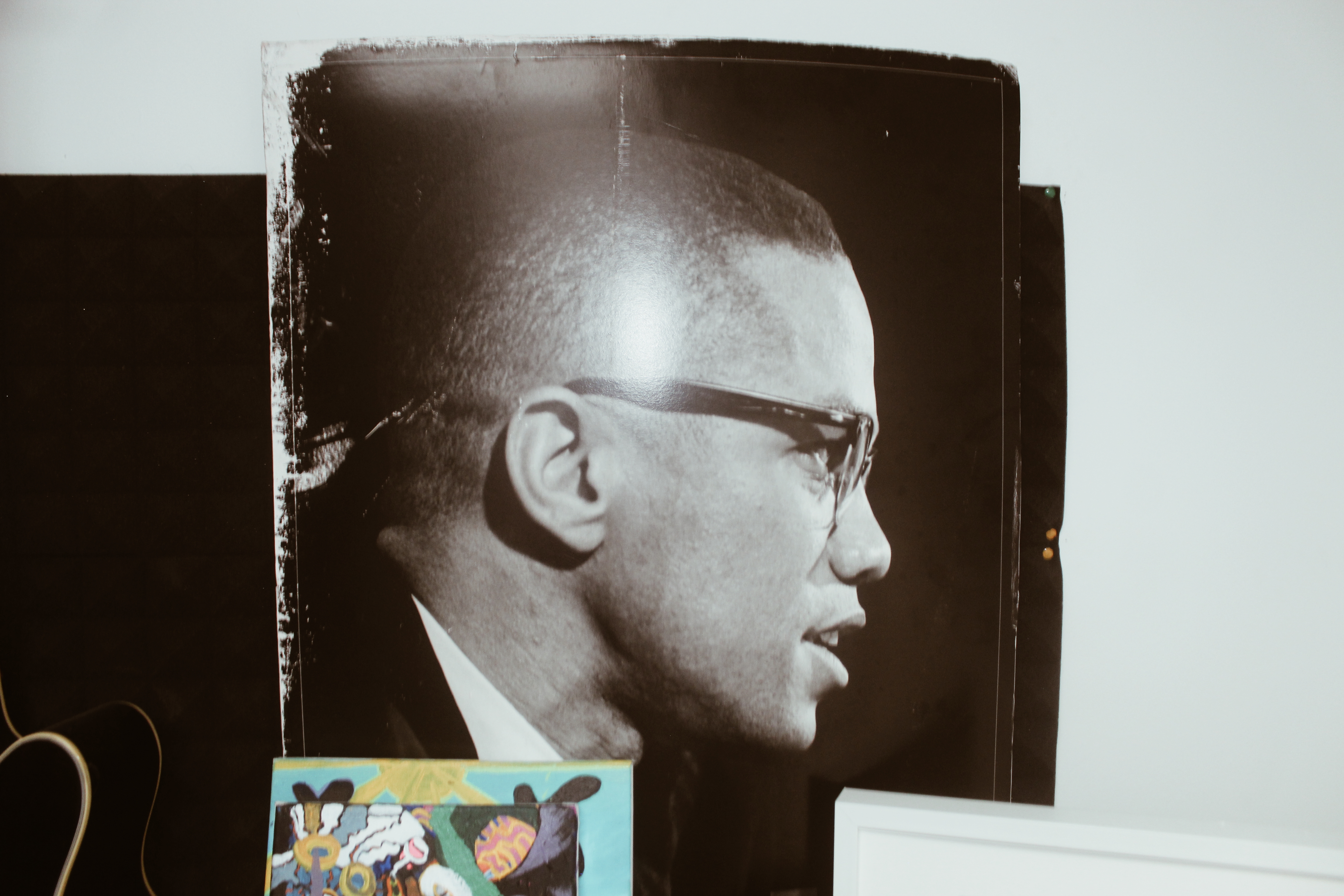

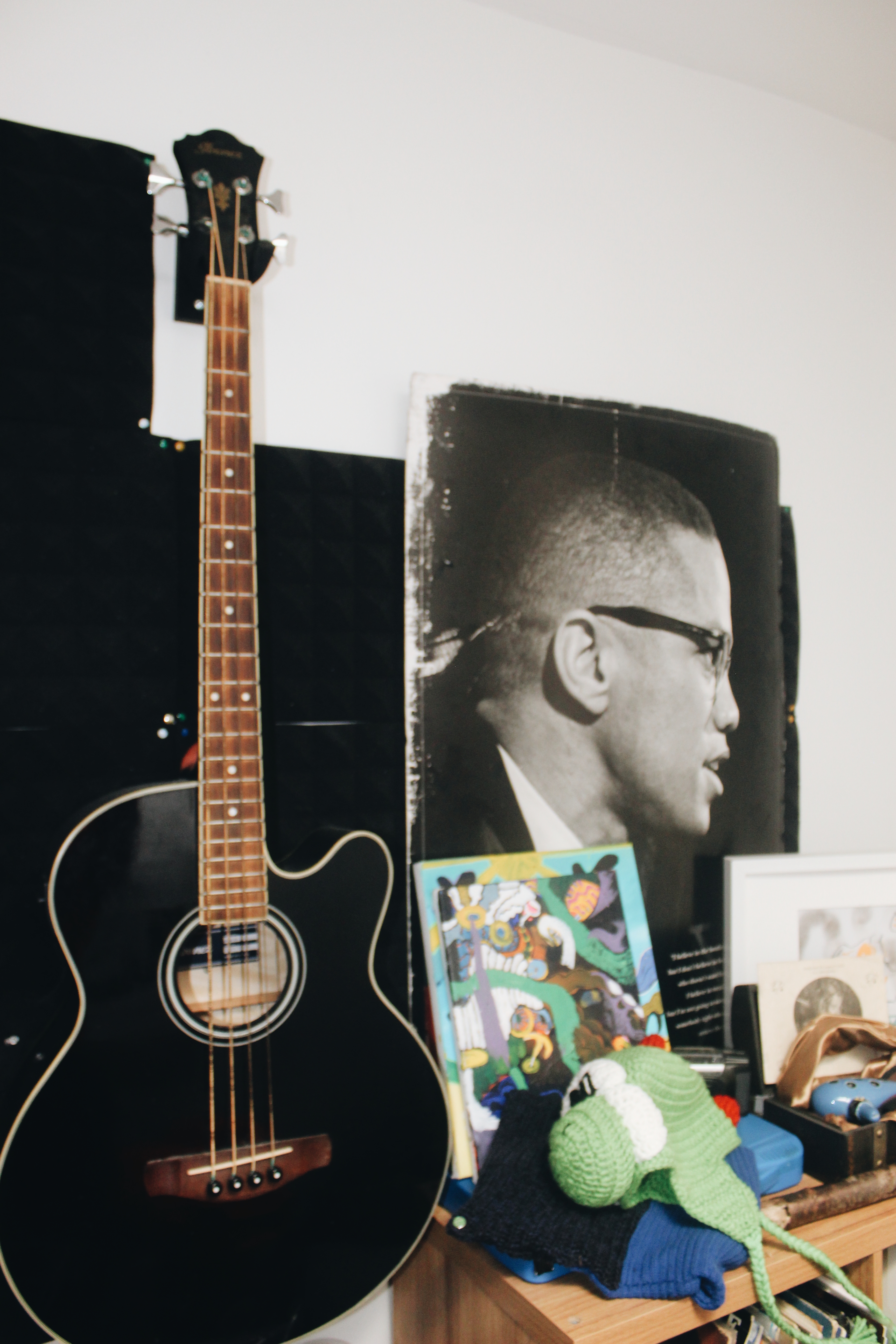

This doctrine is brought to life when, a little over ten minutes after the three-hour mark of our conversation, he takes me to his in-house studio down the hall. It’s a cozy room with a trippy purple and green rug, a few keyboards and a series of guitars hoisted up on individual stands; a domineering poster of Malcolm X’s side profile sits directly across a Supreme skateboard bearing Michael Jackson’s image on its back, and a jungle of mini-amps and wires populates the floor. The afternoon sun is shining through a square skylight built deep into the ceiling, as a grinning Evans pulls up a drive of over one hundred files of unreleased music on his desktop—some of which he plans to put on a forthcoming foghornleghornn LP.

The first song he shows me is a slow-burner, looped with a chord progression so harrowing-yet-transcendental that, at certain points, I find myself squinting my eyes. With the same voice that screeches “I just wanna die” over boisterous guitars in Blair tracks, Evans croons softly about the regality of the mundane. Existential questions are paired with digitized instruments that seem to punctuate themselves with the same exact question marks. If you listen closely, you can hear Evans’ little brother humming in the background—the two had been up together in the wee hours of the morning after a family medical scare, and as Evans played the loop over and over again, his brother stayed the night alongside him. Directly across the hall from the studio, there is a painting Evans made to coincide with the track: on it, two surfers, representing the brothers, make their way across waters that seem larger than either could ever imagine, without looking the least bit afraid.

“All I do with everything I do is figure it out while I’m doing it.”

Another file Evans shows me begins with a haze of 808 hits and hyper-sped soul samples. He’s contemplating whether he should put lyrics over this section or not. After about a minute or so, the track shifts to an interval of jarring, Yeezus-esque electronic drum blitzkrieg, shortly followed by the triumphant emergence of a sort of speedy, tightly-wound, Neptunes-Kanye crossover club bop backbeat. “Pray for me, pray for me, pray for-” a squeaky female voice belts at some points. It sounds like the kind of thing that a Boston Dynamics robot would play to celebrate finally learning how to bypass Google’s security questionnaires, thus unlocking the key to world dominion—in simpler terms, the kind of cathartic funk that would rule the world if humans went extinct.

“I’ll never be as assertive as Kanye,” Evans raps in the track’s lyrical opening. His voice is a perfect fit for the song’s rapid pocket, and the feat of him keeping up alone makes every bar—from Patia Borja shoutouts to in-studio BMs—feel like it’s magnified beyond what the speakers, which are facilitating a mini-earthquake on the floor, could ever accomplish.

After another three hours spent in the studio, I ask him to cue the song up again as I prepare my things to leave. And as I walk out of the room to grab my jacket and put my shoes on, somewhere inside the black of the desktop screen, the hazy reflection of Genesis Evans is lighting a joint.

One reply on “Genesis Evans”

Man good ass read. Crazy u got to hear the songs that would be on 8 songs like a year in advance