Björk’s Punk-Surrealist Cult of Personality

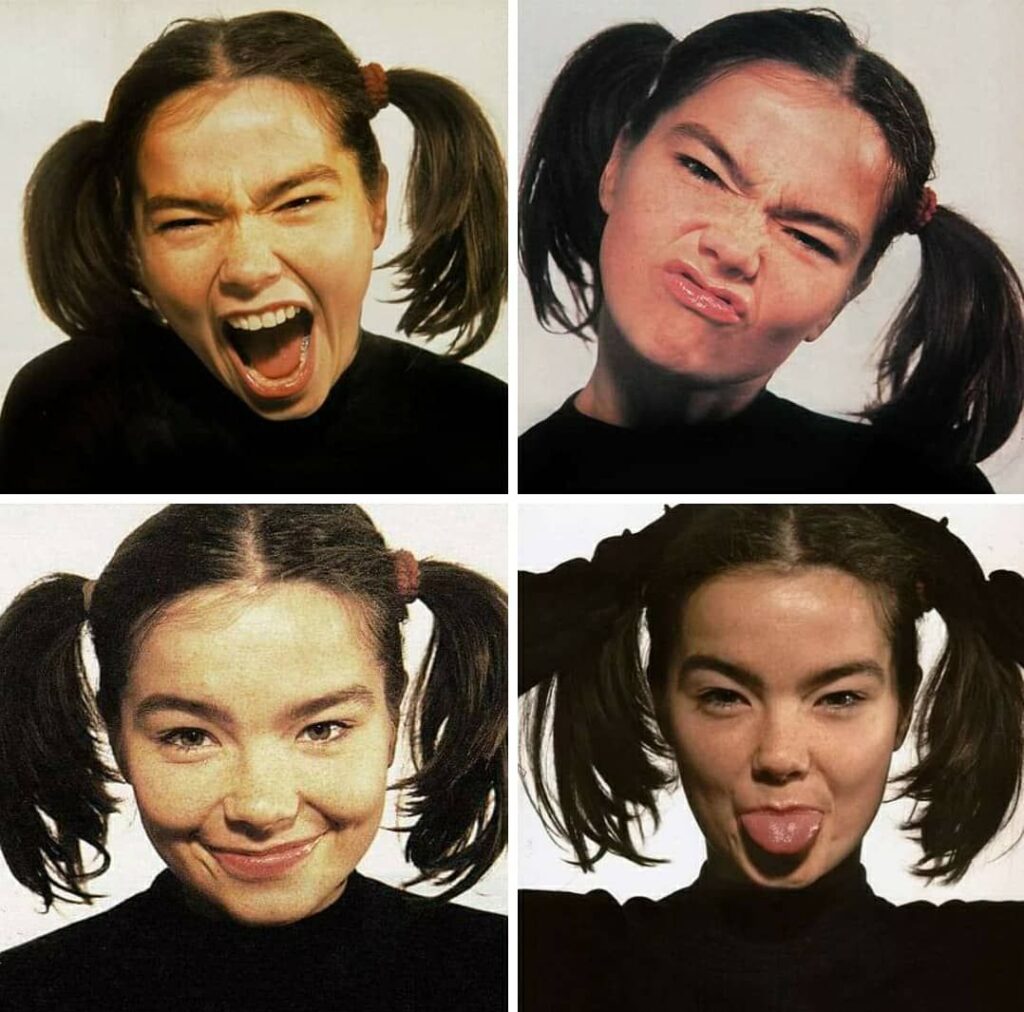

Ever the living LSD tablet, Björk invites revelers in with her playful ethos, then hooks them into an inescapable world of colorful catharsis.

🌐 * DEEP-DIVE* 🌐

SAMUEL HYLAND

In an original recording of “Cover Me,” the harrowing penultimate track to her breakthrough 1995 album Post, Björk’s voice is accompanied by a seemingly-exaggerated echo, a smattering of crackle-pop noises, and numerous irritating-albeit-intermittent squeaks. Right in line with what firebrand esotericism is exuded by the song itself, these sounds were conjured not by in-studio rumblings nor digitized effects, but the bat-infested recesses of a Bahamian cave—upon being given the opportunity to record Post across the ocean from her native London, rather than strictly focus on the metaphysics of her music, Bjork’s intent was just as hellbent on marrying it all to the physics of the terrestrial. The product is one that walks the same tightrope as its mastermind: there are raging dichotomies between being estranged and understandable, down-to-earth and otherworldly, palatable and eclectic. At the end of the day, yet, when resolved on wax, the conflicts all decay into a twisted, whimsical catharsis—and it is at the heart of this debris that Björk finds her home. “I’m going to prove the impossible really exists,” she croons in the cave recording, wielding the playful tone of a witch singing a lullaby. Organs, awkward silences and unabridged nature (larger-than-life water drops, more crackle-pop noises, more bat chirps) overtake the remainder of the track; and even in the absence of Björk’s voice, there is the ever-expanding shadow of the absurd.

Though her career was often fronted by a haze of complex paraphernalia that would suggest otherwise, Björk was, beyond just bat caves, preoccupied with the dual extraction of the rudimentary from the intricate, and the intricate from the rudimentary. In an eerily proto-“Lemonade Mouth” way, the first iteration of her voice on the airwaves was a cover of Tina Charles’ “I Love to Love” (1976), performed at a school recital when she was 11 years old—her teachers loved it so much that they sent it to Rás 1 (at that point, the only radio station in Iceland), which, in broadcasting it, also just so happened to grant an elementary school student the groundwork of a life spent in the public eye. The following year, still 11 years old, Björk released her eponymous debút LP after being signed by the now-defunct Fálkinn Records as a direct result of her newfound virality. The album was a collection of covers translated into Icelandic; her mother, a hardcore hippie who had adamantly fought against the development of Iceland’s Kárahnjúkar Hydropower Plant, took charge over the extravagant artwork: a deifying portrait of the child, backgrounded by a larger-than-life painting of a warrior on a horse. Björk was signed across the top of the canvas in a kind of pseudo-Arabic drawl—for as much as the songs encased were reimaginings of ones that already exist, the cover alone insinuated the genesis of a new movement. Bursting with the clairvoyant implications of her career writ large, nearly twenty years later, Björk would wail the same love-centric gospel in the same cover-song package: this time to millions of enthralled fans worldwide, and as a cover of Betty Hutton’s 1951 big band ballad “It’s Oh So Quiet.” “The sky caves in,” she sing-shouts in recitation, “the devil cuts loose, you blow, blow, blow, blow, blow your fuse!” With every “blow” it sounds as if something is indeed blowing up within her, vocal cords surrendering under duress as the impassioned debris escapes her core.

“-rather than please the crowd with what it expected, she seduced starstruck revelers with proof that the impossible really existed, channeling her eclectic craft to dangle the key to it in their faces.”

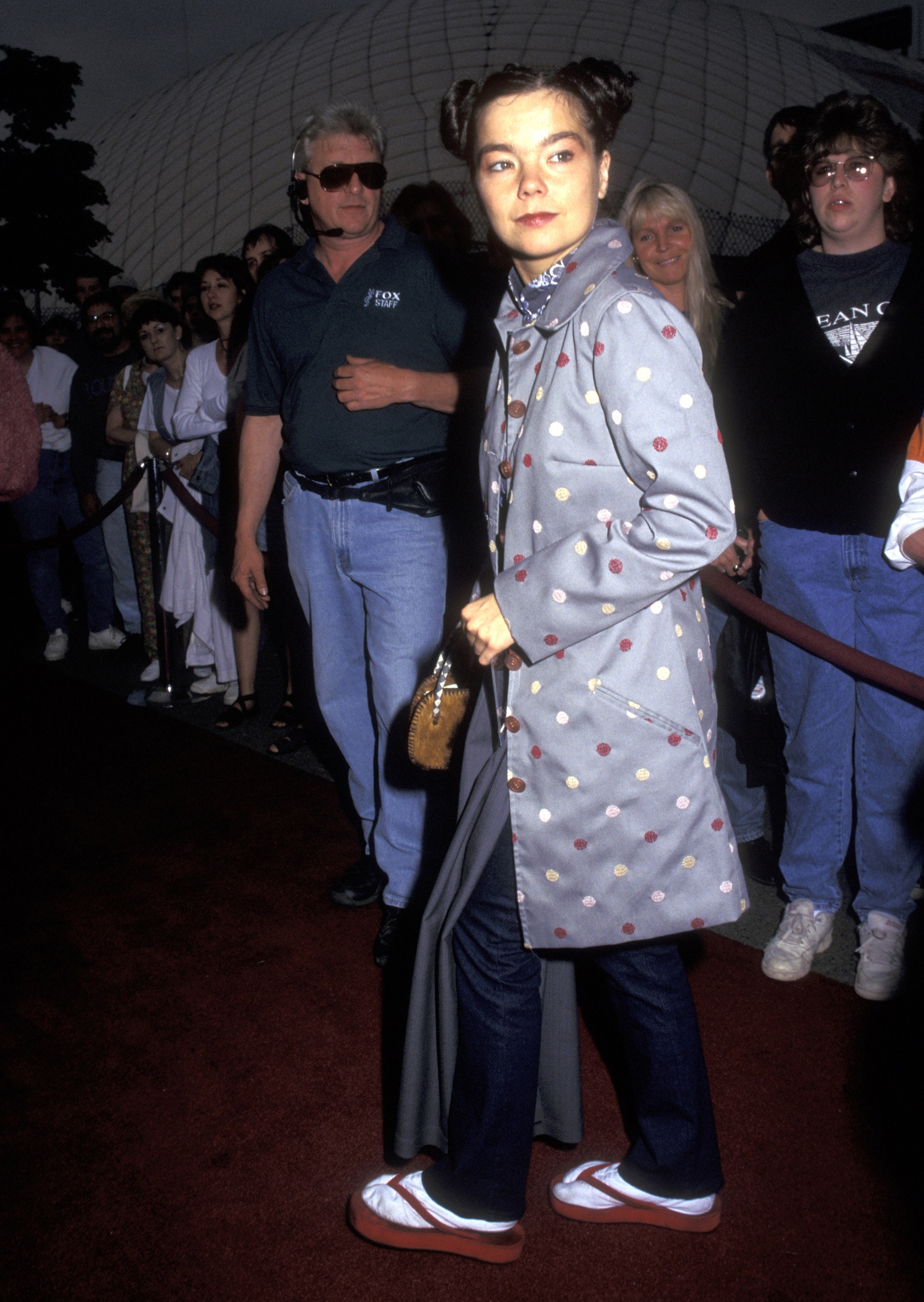

The essence of Björk’s approach is typified by such artistic iconoclasm, albeit rooted in a fundamental love for two things: (1) love itself, and (2) everything, both physical and metaphysical, within its reach. It is very easy, and probably not too far off, to imagine the singer as a Disney princess frolicking to and fro through life with the sole beacon in the arc being a set of redeeming, thematic virtues. In her case, these values seem to oscillate by the moment—when she took to the red carpet of 2001’s Academy Awards in a wearable swan, for instance, it was her glimmering childlike inventiveness that was on display. (Critics called it “one of the dumbest things I have ever seen,” said it “made her look like a refugee from the more dog-eared precincts of provincial ballet,” and concluded that she “should be put into an asylum”). When she recorded vocals in bat-infested caves somewhere in the Bahamas, moreover, it was her unyielding vision for a crossroads between the natural and the unnatural. No matter what, across genres, mediums and messages, the common motif was a lack of reverence for preexisting structures and the audiences conditioned to consume them; rather than please the crowd with what it expected, she seduced starstruck revelers with proof that the impossible really existed, channeling her eclectic craft to dangle the key to it in their faces. And as much as such nature was iconoclastic in essence, its root always circled back to the very thing that first got her voice on the radio: love.

Björk was born in 1965 in Reykjavik, Iceland, a capital city populated with mystical mountainous landscapes, volcanic terrains, and meteorologically extreme summers and winters. At 5 years old, she was enrolled in Barnamúsíkskóli—a revered Icelandic music school—where she would study classical piano and flute for nearly a decade. The incidental combination of enchanting natural surroundings and a precocious musical practice granted the singer, from youth, a dual reverence for the sonic and the earthly that went on to characterize her output for years to come. On her way to school in the mornings, it is reported that she would often use her time alone to sing to the world, whether that entailed pressing her face against the moss to hum, bellowing with the wind, or whatever intimate antics lay in between. When a Rolling Stone journalist interviewed her in 1995, she recounted using a Post promotional trip to Sweden to sing alone in a local forest. “Then I heard some noise, and when I looked around, it was five horses following me,” she said. “And the funny thing was, because I stopped, they stopped as well, they were just standing there pretending they were invisible, with this comical horse expression.” No matter how big she was getting—at the time of the interview, Post had just blown up, and Rolling Stone dubbed her a “punk-turned-diva” who was finally breaking out—she maintained a sort of quasi-fictional, too-good-to-be-true exploratory instinct, forging ambitious and unconventional concoctions in both world and studio.

“And when the various industries she took part in suggested that she ought to have “wishes”—wealth, power, designer red carpet wear instead of swan dresses—she was consistently too busy frolicking in the garden to remember any of it, let alone indulge.”

Because Björk was nowhere near as interested in being a child star as her native music industry was in turning her into one, she opted to reject the opportunity to record a follow-up to her 1977 debút, instead undergoing another several years of studying flute and piano at music school. From there she became involved with a number of upstart punk rock bands in the wake of the genre’s rapid spread through Iceland, bearing monikers that translate to “Cork the Bitch’s Ass” and putting forth albums with titles that translate to “Bite Hard Into Hell.” As part of a group called Tappi Tíkarrass, she graced the cover of Rokk í Reykjavík, a 1982 documentary centered on Iceland’s burgeoning alternative music scene. The photo sees her doll-like and half-human, exaggerated round blushes on her cheeks, tilting like an animatronic at Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory whilst clutching the end of a microphone. One year later, she would join a band called Kukl (“Sorcery” in Icelandic) upon being invited along with an assemblage of other musicians to play the final show of a dissolving radio program; with Björk developing a signature vocal edge seasoned with screeches and shrills, they went on to sign a record deal with the Crass art collective, embarking on an ascent that saw them become the first Icelandic band to play at Denmark’s Roskilde Festival.

After years spent going from unrealized punk project to unrealized punk project, Björk found her first taste of mainstream success as a member of the Sugarcubes, a bizarre alt-rock faction that arose from the rubble of Kukl’s breakup. They released their first double A-side single “Einn mol’á mann” on her 21st birthday; it was followed by 1987’s “Birthday,” which, upon release, was dubbed “single of the week” by Melody Maker. Upon signing a U.S distribution deal with Elektra Records, they recorded Life’s Too Good (1988), selling over one million copies worldwide. The album sounds like a stark manifesto of controlled chaos—on “Coldsweat,” the voice of Björk pierces, audaciously, through guitar assemblages that register sonically as jagged glass shards. “Deus” sees the singer croon mystically enthralling tunes about a man that “does not exist” (punctuated with asides by the monotone voice of keyboardist Einar Melax: “I once met him,” he says, rather creepily, at one point. “It really surprised me… He put me in a bathtub… Made me squeaky clean… Really clean”). “Delicious Demon” plays host to Björk’s familiar wail serenading the titular figure, corporeal cracks in her voice giving rise to the suggestion that it is somewhere within her, fighting to get out. The Sugarcubes achieved monumental success globally, performing on Saturday Night Live in 1988 and being crowned the “biggest rock band to emerge from Iceland” in a Rolling Stone biography. “The Sugarcubes make music that is very much like Iceland itself,” music critic David Fricke wrote at their height. “-A collision of extremes that can be at once forbidding and mysteriously compelling.”

Somewhere between Björk’s stint in a million and a half upstart punk rock acts and her rise to prominence with the Sugarcubes, she made her film debút in Nietzchka Keene’s adaptation of The Juniper Tree, a spin on the original Brothers Grimm fairytale that sees two supernatural siblings vye for safety under the tutelage of an estranged mother. Björk plays the character of Margit, a clairvoyant younger sister who often stares into the abyss with intense eyes, seeming to carry the shadow of the supernatural along with her everywhere she goes. In one haunting scene, she approaches her sibling in a vast expanse of empty, grassy hills, abashedly twirling a flower in her hands. “I don’t know if I have any,” she says, when asked about her wishes. Her voice comes out in a timid-yet-shrewd silence, the only hint of her shrieking command of the microphone being an eerie echo. “You always say I do. But I never remember anything.” As grim as the moment is in context of the film, it is, doubly, yet another inflection of Björk’s strikingly childlike, Disney-princess purity: while the rest of the world worked itself into a consumerist craze as she rose to fame, she opted to remain—whether mentally or physically—enveloped in the nakedness of nature, rejecting a slew of conventional commercial structures in the process. And when the various industries she took part in suggested that she ought to have “wishes”—wealth, power, designer red carpet wear instead of swan dresses—she was consistently too busy frolicking in the garden to remember any of it, let alone indulge.

The late 1980s saw Björk go through a series of breakups, the first being a divorce with Sugarcubes bandmate Þór Eldon after the birth of their first child, and the second being a split with the band itself, though she was obligated by contract to record a final album with them before she could effectively make an exit. She moved to London, inaugurating her journey as a solo artist with 1993’s Debut (the album she recorded at 11 years old isn’t counted as part of her discography, because it is reputed to be juvenilia work). The record was intended to signify the start of something new; and, at this stage in her career, a definitive fresh start was something much-needed: long another stick of indistinct detritus in the heap of Iceland’s fading alt-rock renaissance, her solo act would be tasked with lifting her into her own esteem, beyond her convoluted past and into a more coherent future.

Debut somehow manages to channel both elements at once—it’s a complex array of eclectic musical approaches, yet it is in this very haze that Björk supernaturally, as always, strings together something that feels like home. On “Big Time Sensuality,” for instance, exactly one track after she croons somber, acoustic-backed romanticism on “Like Someone in Love,” she unleashes a bass-heavy, futuristically electro-pop dance number straight from the ballroom of an extraterrestrial coming-of-age film, pulsing with the same exact thematic agenda as the jarringly different track that just faded out. On the album’s cover, a stark contrast from the last debút project she recorded as an 11 year-old, she is pictured monochrome and stoic, holding her hands up to her mouth with eyes that seem to pierce through the lens. It’s a mournful image, one that well encapsulates the album’s pretext: from her departure from both earthly and musical homes, to her divorce from her husband soon after birthing a child, Björk did, indeed, have a great deal to mourn. Still, albeit, Debut exudes a dance-in-the-rain quality omnipresent across the singer’s pneuma—no matter what, it seems, the Icelandic Cinderella always finds her glass slipper.

“Here is where Björk became a perennial gateway drug, not to one sound but to the unknown, which is to say the future.”

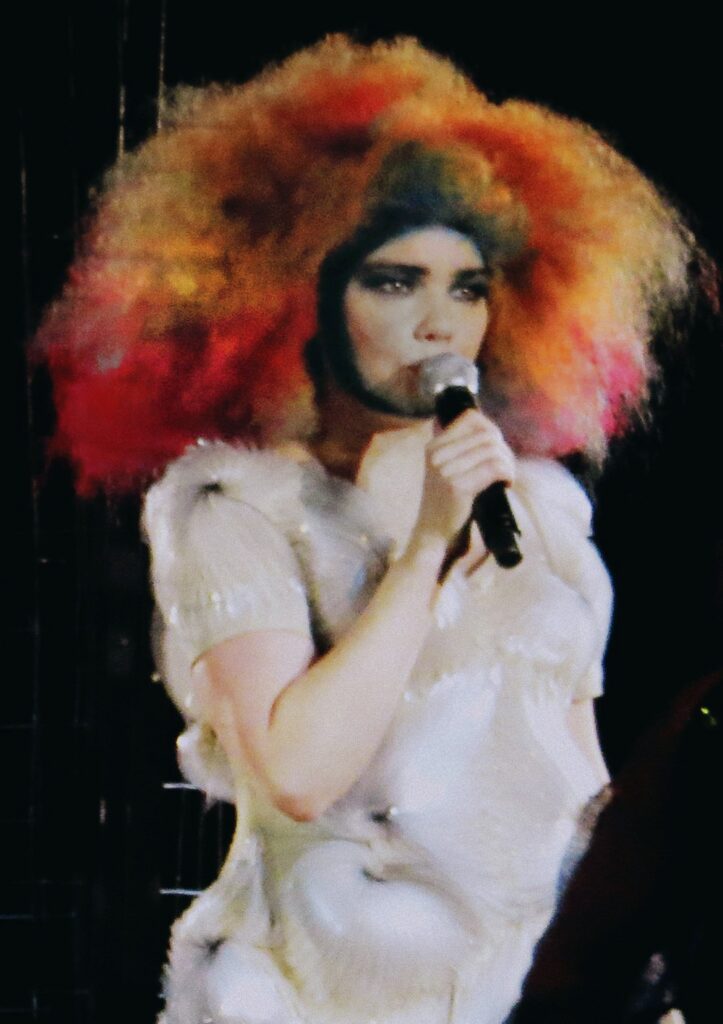

Björk followed up her (second) solo debút with 1995’s Post, in doing so, effectively striking gold with international audiences. Post sees Björk as both relatable and endearingly strange as ever, animating scenic arrangements with her shriek, and wielding her masterfully-honed storytelling ability to craft living, breathing, modern-day fairy tales. Most notable of these fables is likely that of “Isobel.” Over a busy soundscape of Africanized percussion and eerie, oscillating keys, she paints the titular character—“Isobel” rather than “Isabel” per her self-isolating ways—as a woman who completely distances herself from the complexity of the outside world, eventually going on to clash with urbanization before retreating back to her home in the forest. “My name Isobel,” Björk croons, voice wavering as if involved in the subject’s warfare. “Married to myself, My love Isobel, Living by herself.” The music video for “Isobel” seems to exist in the same barren universe as her character in The Juniper Tree: in a trippy, disorientingly creepy back-and-forth between the singer performing and a group of people watching the story play out in the reflection of a stream, it purports itself as a fever dream, fading out with the haunting image of Bjork’s estranged head resting at the bottom of a waterfall.

“With Post, Björk set the bionic foundation for one of the most consequential careers in pop history,” Pitchfork contributing editor Jenn Pelly wrote in a review of the album. (It received a perfect score). “Here is where Björk became a perennial gateway drug, not to one sound but to the unknown, which is to say the future.” In order to be a gateway drug, any substance must be able to fulfill two sets of criteria: the first of which being capability to attract, and the second of which being the capability to hook once the attraction is established. It is in this sense that Björk functions as not only an iteration of introductory narcotics, but their quintessential human manifestation: like a living LSD tablet, she invites revelers in with her playful ethos, then hooks them into an inescapable world of colorful catharsis.

Speaking to the aforementioned Rolling Stone journalist, the Brazilian musician Eumir Deodato described Björk as having “developed a style and a music that I’ve never heard anything like in my life.” He continued: “When I heard her material, I freaked out, and I said, ‘What are you doing? This is crazy, this is so difficult, to propose this kind of style to the people.’ But she does, and she’s successful at it.” Listening to Björk is, essentially, embarking on the same psychological step-by-step sequence: first comes doubt, then comes enjoyment, then comes addiction. There is a semi-popular video of Johnny Damon stealing second and third bases in the same play during Game 4 of the 2009 World Series; as he takes off for third, managerial staff in the Yankees dugout shout in disapproval, then once they see that he’s going to make it, they quickly pivot to jubilant encouragement. Oddly, Björk’s artistic oeuvre is strikingly similar to Johnny Damon executing a double steal—when she records her vocals in cave-filled bats, wears swan frocks to red carpet events or takes a break from album promotion to sing to horses in a local forest, the naked eye is seduced into an almost knee-jerk revulsion. But, much like Damon, when it becomes apparent that she’s somehow still standing—whether howling over sonic glass shards, clutching a microphone like a Wonka-manufactured animatronic, or revitalizing age-old ballads of wartime romance—the only option left is to cheer her on. The inadvertent cult of personality she enjoyed in the 1990s banked heavily on this quality; it was difficult to understand why or how Björk was doing it, but the fact that she was doing it alone made being an audience member more of an honor than a formality. Pretending you got it could have been just as fun as getting it itself.

“-when you give people a world to live in, even if it isn’t truly theirs for the physical taking, the ever-so-slight possibility exists that they will also make it a hill to die on.”

Years removed from her initial breakthrough as a solo act, Björk would go on to facilitate a collaboration with the revolutionary New York rap supergroup Wu-Tang Clan, seeking to have group leader RZA contribute beats to her 1997 LP Homogenic. Although that specific endeavor fell through, she was able to reconnect with the faction beyond music on several occasions—one being at a book signing of hers in New York City. “ I turned up,” she told Fact in 2017, “and seven of the Wu-Tang Clan turned up to, like, protect me! I was signing books for an hour, and they sent some of their team, standing there with me. That was one of my all-time favourite moments: I had been on my own, so when they turned up I felt very protected. It was magic. In my eyes, they’re punk. We are definitely [similar] – we do things in, like, a ritual way.” Even outside the context of any strategized, public-facing body of work, Björk’s innate impulse to see the most disparate universes collide made her a walking crossroads, inadvertently carrying with her a lifetime’s worth of eclectic scenes. In Björk’s world, a thuggish collective of East Coast rap heroes acts as the army of an Icelandic Cinderella with a history in foreign alt-rock—and not only is it normal, but it’s just the way things ought to be. The only two options are the same ones available for all puzzling snapshots of her career: take part, or walk away.

⛓️ ⛓️ ⛓️

Unfortunately, with encompassing cults-of-personality like that manufactured by Iceland’s Cinderella, as much as there is a sort of inescapable pull, there is simultaneously the desire to somehow prove for oneself that the fantasy exists—an objective that can go lengths heinously far beyond what original intent lay behind the muse. Over the mid-1990s, Ricardo López, a Georgia pest exterminator, began to grow increasingly enthralled with Björk and her music. He had rapidly deteriorating self-esteem and a reclusive inclination; as he sought more and more to escape reality and cling to whatever fantasies he could get hold of, Björk’s artistry was functionally a perfect nook, complete with illusory visuals, captivating soundscapes and a foundation in mystical nature. A sufferer of Klinefelter syndrome, he was long awkward with girls, dropping out of high school to pursue an artistic career, albeit never going far due to a crippling fear of being rejected. López’s escape of such grim realities was being obsessively infatuated with celebrities, Björk being at the center of his attention: he studied information about her life, paid concerning levels of attention to her career, and directed numerous fan letters to her home address.

Over a number of months, López put together a video diary chronicling both his infatuation with Björk and, consequently, his mental decline. Upon reading in Entertainment Weekly that she had been in a relationship with the British musician Goldie, he grew furious, and quickly began plotting revenge for what he perceived as a stark betrayal (“I wasted eight months and she has a fucking lover,” he wrote in his physical diary before pivoting to video). To López, as put in one of eleven video diary entries, the intent of his recordings was to chronicle “my life, my art and my plan. Comfort is what I seek in speaking to you … I am being my own psychologist. You are a camera. I am Ricardo.” Growing angrier and angrier with Björk as the installments went on—the extent of his betrayed mindset is perhaps best understood with knowledge that his diary (all 803 pages) contained 168 references to López’s feelings of failure, 34 references to suicide, and 14 references to murder—his plan to “punish” Björk escalated from minor infractions to, finally, full-scale murder: the final plot was to mail a bomb to her home and commit suicide on the same day, the intended end being for the two to reunite in heaven.

“I make music, but in other terms, you know, people shouldn’t take me too literally and get involved in my personal life.”

In his final video diary entry, titled “Last Day – Ricardo López,” López sat in front of a sign that read “The best of me. Sept. 12.” He nervously prepared to make his visit to the post office, then resumed filming upon returning to his apartment, where, visibly naked, he painted his head red and green. Loud Björk music played in the background as he examined himself in a mirror. Then, as “I Remember You” faded out, he shouted “This is for you” and shot himself in the mouth with a revolver.

Upon discovering López’s corpse several days after the incident, the Broward County Sheriff’s Office got hold of the tapes and effectively intercepted his package before it could reach Björk’s residence. In a statement, Björk said that she was “very distressed” about the incident. She sent flowers and a card to López’s family, and hired security to escort her son, Sinder, to and from school. “I make music, but in other terms, you know, people shouldn’t take me too literally and get involved in my personal life,” she shakenly told reporters outside her home as the news broke. “I make music for people, you see.”

As much as (1) the extent of carnage initially devised failed, and (2) Björk was in no way at fault, the saga still outlines a harrowing underbelly of creative universes even as colorful and lively as her own: when you give people a world to live in, even if it isn’t truly theirs for the physical taking, the ever-so-slight possibility exists that they will also make it a hill to die on. Not only does Björk’s music radiate eclectic otherworldliness; it invites listeners to indulge in what infinite candylands are advertised—though it seems common knowledge that the way to go about such mysticism is to return to the real world no matter how long it takes, for some, those universes are too enthralling to abandon. The same life-affirming, nature-embracing music becomes a death trap. And once the substance leaves the control of the source, no matter how innocently or monstrously so, it takes on whatever form the consumer allows it to.

The term “Stan” began being used to describe obsessive fans following the release of Eminem’s 2000 single of the same name, wherein the titular character murders his immediate family and kills himself upon not getting a response to any of his numerous letters to the musician. Up to present day, the term has come to connote a brand of social media-native superfan, educated on the nitty-gritty details of their artist-of-choice’s career, and quick to jump to the defense—often in packs—at the slightest questioning of what legacy they are sworn to protect against attack. Even so, in spite of its more lighthearted ethos than the sagas of Björk and Eminem’s versions, it remains a dangerous extent of artistic reach that brandishes the same exact harrowing deep ends, if not even deeper, as it did decades ago.

Much of this phenomenon is exacerbated by the internet. As social media allows artists themselves to take on informative roles once championed by news publications and tabloids (today, López would likely have found out about Björk’s relationship on Twitter and not Entertainment Weekly), the presence and silence of a celebrity figure alike may each give way to conversations all-but-guaranteed to outlast original intent. Perhaps this is more obviously true for the silence: when big musicians like Kanye West and Frank Ocean go quiet for longer than usual, the narrative ritually eclipses them, with increasingly wild theories serving as footprints of increasingly desperate fanbases. Even for the opposite approach, notorious social media loudmouths like Nicki Minaj and Soulja Boy inadvertently, with their passion, rile up fans to a point where whatever is given them, even if not a direct call to action, is taken and run away with.

“-she didn’t need a red carpet to possess people, and before the internet could carry her message for her, it was her output alone that both brought people into her world, and made it a graveyard for those who couldn’t get out.”

In Minaj’s case, for instance, upon catching wind of a critical tweet from writer Wanna Thompson that made a point of her age, she retaliated in a series of scathing direct messages that were soon made public. “When ya ugly ass was 24 u were pushing 30?” one of the DMs read. “I’m 34. I’m touching 40? Lol. And what does that have to do with my music? Eat a dick u hating ass hoe.” Devoted Minaj fans pounced on the matter once it reached their Twitter feeds. “Ms. Thompson said she has received thousands of vicious, derogatory missives across Twitter, Instagram, Facebook, email and even her personal cellphone, calling her every variation of stupid and ugly, or worse,” the New York Times reported in 2018. “Some of the anonymous horde included pictures Ms. Thompson once posted on Instagram of her 4-year-old daughter, while others told her to kill herself. Ms. Thompson also lost her internship at an entertainment blog in the chaotic days that followed, and she is now considering seeing a therapist.”

The loudest fans on the internet, whether their respective artists are outspoken chatterboxes or silent personages, are fueled by creative ephemera that is gripping enough to be passionately defended—when the silent artist neglects to speak for themself, the captivated audience, mobilized by the music, feels responsible to argue on their behalf; all the same, when the outspoken artist invokes diversity of opinion with their ever-running mouth, the audience, just as captivated and emboldened by the music, feels the need to jump to the defense of what first showed them the light. Björk exists in a strange in-between, in that when she’s talkative, it isn’t in a self-righteous sense, and when she’s not talking, it isn’t in the off-the-grid context of a Kanye West or Frank Ocean. Her too-good-to-be-true eternal childhood transcends the existent structures of social media and its marriage to modern-day artistry, and even without a fully-realized internet to inflame the obsession she channeled, it allowed an extreme case like that of López to remain possible.

When, every few years or so, social media holds contentious debates on whether (insert 20th Century artist here)’s fanbase was bigger than that of (insert 21st Century artist here), videos often circulate of young women fainting at the sight of Michael Jackson, Madonna being greeted by camera flashes and raucous mobs, or Yasiin Bey freestyling at the center of a captivated swarm in New York City. Though similar images are not the first to come to mind when Björk is brought up, with an especial consideration of what impact she had on people like López, it is beyond necessary to include her in such a pantheon: she didn’t need a red carpet to possess people, and before the internet could carry her message for her, it was her output alone that both brought people into her world, and made it a graveyard for those who couldn’t get out.

🖥️ 🖥️ 🖥️

As of right now, at 53 years of age, Björk hasn’t lost her place, nor her credit, in the international cultural canon. “Twenty-five years later,” Pelly wrote in the aforementioned Post review, “you don’t need to scroll far through Björk’s Instagram feed to find the most audacious young popular artists alive, the likes of Arca and Rosalía, heeding that call, crowning her ‘queen.’” It’s a heartwarming prospect, one that insinuates a passing of the torch to young cultural iconoclasts who will not only disrupt culture in line with Björk’s own rebellion, but hijack it en route to a brand new, compelling tomorrow. At the same time, though, the same prospect is one that begs a question faced by “weird” artists both preceding and succeeding the Icelandic punk-surrealist: what determines who is allowed to stand the test of time, and who isn’t? Björk was not the first, and by all measures, certainly will not be the last, cultural provocateur who finds a playground in going against the grain. We’ve heard the names of many from past and present alike: Dean Blunt, Lou Reed, George Clinton, et cetera. But for the few that have broken surface tension and graced our radars, heaps and heaps of similar eccentricity remain at the ocean floor—why don’t all see the top?

It isn’t that such outputs lack the same transcendence exhibited in discographies like Björk’s own. “It’s so healing-sounding, his music,” the musician Vinyl Williams said of Iasos—a pioneer of the “new age” genre—in a Zoom interview last year. “(But) the thing is that Iasos would not be played in public, generally. I definitely do- whenever I have the chance to play music in public, I put on Iasos.” Williams argued that the music of Iasos would change one’s life given the chance, but because it isn’t often given the chance, it doesn’t wind up changing too many lives after all. Such constructs, omnipresent in present-day alternative music circles, give way to a double-sided consequence: on one hand, there is the inadvertent buildup of a sort of pride-championed elitism among the few that, via what they purport to be a strain of musical enlightenment, actually do have an ear for what exists beyond the mainstream. Then, at the same token, there is a simultaneous buildup of radio silence among those that don’t possess this sonic inclination—at the same time that indie-slash-alternative communities are growing tighter, the invisible security fence separating them from the rest of the world is growing taller. Not only is the life-changing music not being played in CVS. The people that have it often aren’t willing to let it go.

“Without being involved in her personal life, followers were made to feel like longtime friends, enlisted to figure out the world by her side as an infinite map unfolded before their eyes at the same time.”

The issue extends into a larger conversation about knee-jerk cultural protectiveness. When the long-disgraced NFL receiver Antonio Brown once took to Instagram to show off a newfound musical endeavor, brandishing an electric guitar and wearing a cheshire grin above a large Cuban link chain, a majority of commenters were quick to jump on the attack. “You even know how to play that?” one message read. “You holding a guitar is about the most disrespectful thing you could do to any real musician,” said another. “Play me a Dbdim7 chord @ab show me you’re a real one.” “We all kno you’re not smart enough to read music.” “A stain on the tablecloth of humanity.” Pictured here is a micro-level instance of what often allows alternative music to stay barred from both potential listeners and potential creators alike: the sight of an outsider, someone who has long enjoyed the benefits of mainstream spotlight, opting to dabble in the prized possession of those who fought oh-so hard against that exact same current triggers a contention that bites before it grins, pounces before it greets, pushes away before it pulls in. When pop culture-defying acts attract audiences that thrive on such arrogance, the ocean floor becomes a mass grave for both the artists themselves, and the niche group of sonic elitists that kissed their asses all the way to the bitter end.

In most cases that follow similar fatal sequences, as much as elitism may serve as an anchor weighing never-to-emerge acts down, there is also a certain level of complicity to be afforded musicians that fail to do anything about it. The kinds of fanbases that swarmed Brown’s comments section are fostered by figures that purport themselves to be aloof and godlike, seldom building any sort of bridge from producer to consumer, all the while using what platforms they have to project an image rather than reflect a reality. This is what makes Björk’s appeal to listeners, even before the internet era, a cultural feat worth beyond the reverence it has garnered: in an age wherein it was objectively more difficult to establish intimate artist-to-audience relationships, by her princess-esque purity, willingness to be vulnerable in uncharted territory, and ability to craft universes accessible for all willing to listen, she made it feel as though even if you had never met her, you understood exactly where she was coming from. Without being involved in her personal life, followers were made to feel like longtime friends, enlisted to figure out the world by her side as an infinite map unfolded before their eyes at the same time.

“You shouldn’t let poets lie to you.”

In an oft-revisited early interview—1988, to be exact—that aired while a much-younger Björk was still the Sugarcubes’ frontwoman, the singer sat down innocently in a thrifty dress, one skinny arm pressed against her cheek and the other clutching the side of a television box. “Hello. It is Christmas time, and I am sitting here by my TV,” she started, beaming with a candid and guileless wonder. “I’ve been watching it very much lately, because I’m on holiday, and I’ve been seeing all those programs about all sorts of things- about Icelandics being happy about Christmas, very gay, and also very serious and spiritual, and also seeing Icelandic comic people making jokes, which they are very good at. But now I’m curious. I’ve- I’ve- I’ve switched the TV off, and now I want to see how it operates. How it can put me into all those weird situations.” Björk proceeded to spin the television around across the wooden desk before her, walking her audience through a live dissection and analysis of its inner parts. After a few minutes of meddling, she concluded, refuting the period’s technological doomsdayers: “I stopped being afraid because I read the truth. And that’s the scientifical truth, which is much better. You shouldn’t let poets lie to you.”

The late stages of the 20th Century saw a sudden proliferation of new media, and, at the same time, a parallel proliferation of the need to understand said media. It was this exact climate that Björk was manufactured for, her artistry serving as not only a beacon of how malleable the dreaded future was, but a crucial reminder that it was okay to figure it all out as one went along. Her striking candidness, even while fostering a complex practice behind the microphone, made her as personally understandable as she was artistically complex, and the tightrope between compound and convoluted was one she treaded with masterful stasis, regardless of raging sociopolitical waters beneath her.

As we currently brave a similar crossroads between past and future—virtual currencies, digital universes, and ever-expanding tech monopolies challenging our collective understanding of the world—one of several roles of the arts is to do something similar to what Björk did for her own era. Now, more than ever, consumers need artists who, rather than purport themselves to be all-knowing brainchildren of the looming hereafter, meet the public where it’s at… which would be nowhere in particular. The clock is ticking faster than it was in Björk’s heyday, and just as much as the capacity for ambitious art has progressed with time, so has the lack of room for art that pretends to know the answers. Art must be willing to admit that life is directionless; and as life leans further and further into that vein, the time for sonic swindling wears thinner and thinner.

A stirring 2000 Daily Mail print story currently making rounds on social media bears the headline “Internet ‘may just be a passing fad as millions give up on it.’” “Researchers found that millions were turning their backs on the world wide web, frustrated by its limitations and unwilling to pay high access charges,” the report reads. “They say that e-mail, far from replacing other forms of communication, is adding to an overload of information.”

If the information was overflowing twenty-one years ago, it has long exceeded the invisible boundary line up to now. But the void that Björk filled that much time back, and one that creatives must fill today, is one of turning the information—no matter how incomprehensible, socially-coded, or dystopian—into the makings of a universe that everyone can both claim, and figure out, as their own. The kind that makes life an escapade and not an escape.“I think I’m Tindered to life,” Björk told The Guardian in 2017. “I’m dating life. I’m like: ‘Oh, those are new hands and I’ve got new legs and new… it’s a feeling of… It feels like a new adventure.’”