SAMUEL HYLAND

Shrouded in silence and enslaved to intimacy, an assertive out-of-frame interviewer sits inches away from his subject. Across from him, a crazy-haired, dark-skinned, turtleneck-clad man stares thoughtfully into space.

The question is posed: “Is there any anger in you? Any anger at all?”

“Of course there is,” the man responds. The answer comes with vehemence and rapidity, nearly cutting off the inquisitor before he can finish his sentence.

“What are you angry about?”

Now, silence. The subject’s gaze wanders about the room. Sporadic half-smiles are mixed with muffled utterances of deep contemplation.

Thirty seconds pass.

“I don’t remember.”

Given the chance to ask Jean-Michel Basquiat the same question at the height of his artistry in the 1980s, one would be extremely fortunate to get much more of an offering out of him – let alone an interview to begin with. But – take a look at his art, and the answers are all there: bloodied black men, crossed out SAMOs, and screaming skulls being three of many pointers.

The speechless artist has spoken on the canvas for centuries.

In instances like that of Basquiat, such voicelessness is voluntary; artistic recluse is intentionally put in place to challenge consumers into separating producer from product.

But, in other cases, voluntary reclusion cannot be a factor. Tape has been plastered over the mouth. Art is the only way.

To commemorate those who have been silenced by our society over centuries of injustice, follow this digital itinerary of works within the Met collection showcasing decades of a struggle for true equality within America. These pieces evince frustrations experienced from various timestamps of suppression – from a mother and children bent upon overcoming the bondage of sharecropping, to an African American shoemaker too large for more than one box, and a young man bold enough to stare modern-day inequalities centuries strong in the face.

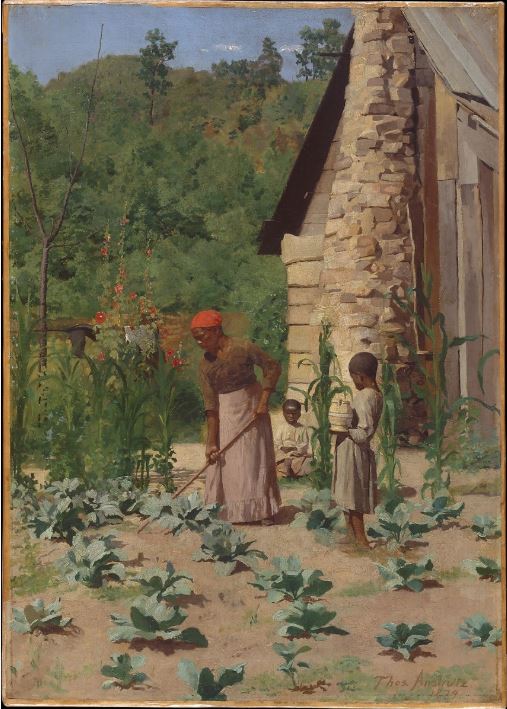

The Way They Live – Thomas Anshutz (1879)

When Thomas Anshutz traveled to Europe between 1882 and 1883, he rambled in his journal of a man, hands “prostituted with the temper of water of the queen of darkness, but nothing”.

Just three years prior in the mountains of Wheeling, West Virginia, he had seen all three – the man, the water, and the darkness – in living flesh. Respectively: The African-American, his yet-to-be-seen promise of freedom, and the white force preventing an intersection between the two. Anshutz was, by birth, a member of the latter race. The painter spent one half of his childhood within Newport, and the other in the aforementioned West Virginia town. So, what makes his 1879 piece significant is just as much context as it is content: a member of the race benefitted by such injustice puts on a rare display of acknowledgement for how a promise is further kicked aside – something the said party is knowingly guilty of.

The Way They Live embodies resistance in its title alone: Not the way we live – the way they live; the oft-dismissed disparity is catapulted to the forefront. Beyond the name, though, it is the nuance put forth by its characters that brings suggested disproportion to full comprehension. Anshutz does not portray smiles, flowers, nor any symbol of life whatsoever. Rather, a mother and her two children are depicted with downcast, unsmiling eyes. The color scheme of the canvas is defined by the murky green of shrubbage, the dirt-esque hue shared by the sharecroppers, the ground, and the housing unit; the barely noticeable blue of the sky. The most abundant crops in the frame are weeds.

Prostituted by the temper of freedom in the palm of an oppressive force, the African-American family struggles to find hope in a field populated by the corpse of hope itself.

“But nothing,” writes Anshutz in his journal.

They must continue to plow, eyes downcast, hearts set on a freedom long kicked aside.

The Shoemaker – Jacob Lawrence (1945)

Decades before lung cancer got the best of him at the turn of the century, Jacob Lawrence garnered acclaim amongst both black and national audiences alike for pieces that shamelessly epitomized African-American culture.

“As children of the Harlem community, we grew up being told about these great heroes and heroines,” he told Xavier Nicholas in a 1994 interview. “-I naturally wanted to tell their stories.”

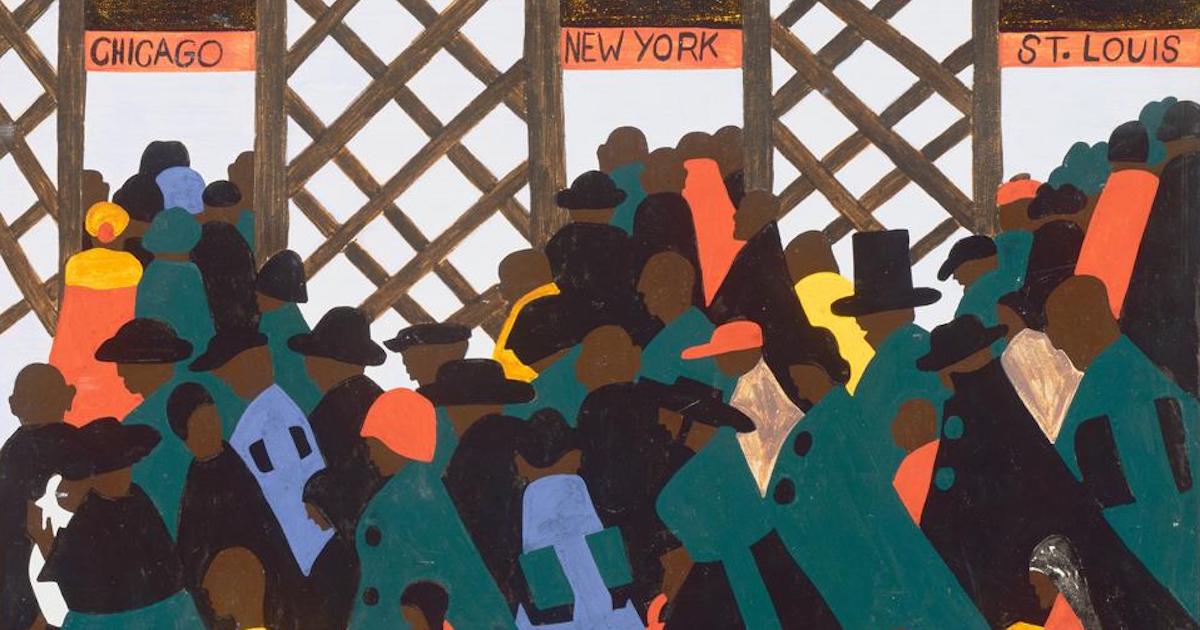

To Lawrence, heroes and heroines were the men and women with whom he shared Harlem’s streets. By 1941, with the release of his Migration of the Negro series, the tales that graced his canvases reached heights Afro-American narratives were rarely granted – all sixty panels of black history going on display at the Museum of Modern Art when Lawrence was only 23 years old. In years beyond that, the painter’s legends dared to grind against the shifting culture of the 20th Century. They were not fictional. They were not prejudiced. Jacob Lawrence painted living fables of Harlemites content within their own dark skin, no matter the predicament imposed by a society that vowed to make them feel otherwise.

The Shoemaker was painted shortly after Lawrence was discharged from military service in 1945. In it, a cumbersome, overall-clad black man appears to struggle within the stark confinement of his new workspace.

In his struggles, however, his eyes are wide open. He is determined.

When African Americans were thrust from lives in field labor to careers in what Malcolm X deemed the “white man’s businesses,” millions of ‘shoemakers’ were born into the U.S. They weren’t prepared for change – America simply evolved on its own accord, and the minorities it had long exploited were forced to adapt to the box they had been thrust into.

Lawrence’s piece showcases, through one large man, the resilience of a race ensnared in a box long outgrown.

New York City – Jacob Freed (1963)

If one uttered the words “New York City” to any 19th Century abolitionist en (speculative) route to freedom, the most likely image to undertake the subject’s mind would be that of exactly what he is searching for.

If you uttered the same three words to a demonstrator of the same exact cause – freedom – one-hundred years later, the most likely image to undertake his mind would be strikingly similar to the above photograph.

When Leonard Freed took to the streets alongside Martin Luther King Jr during the Civil Rights movement, his motive was not of mere solidarity; rather, he sought to document the complex after which he named his first book: Being Black in White America. As insinuated by the title, it was not a matter of coexistence. Black and white men lived in the same country – but in the United States, the latter was simply living in the former’s world.

New York City is what happened when the oppressed attempted to make coexistence an option.

In the snapshot, an unidentified African-American man appears to be caught within a violent struggle against two New York City Police officers. Certain things are unclear. We don’t know whether there was resistance, nor if any apprehension was justified, let alone what occurred in the first place.

What we do know, though, is what we see: A hand on a man’s neck, a hand clasped around that hand as if desperate to remove it, one mouth open for air, and another open as if to clue at underlying intent. The apparent “malefactor” is well-dressed.

For what had been centuries even at that point, the African-American race spent its entire life having “dressing itself” for the grand ballroom that was American society – only to, once at the door, be not only turned away — but deemed a criminal.

To this day, the “liberated” African-American remains a criminal to the white world in which he lives.

The hand on his neck is now a knee.

History Refused to Die – Thornton Dial (2004)

History is called history because it is the past – but history is not history when it is still happening.

The majority of Thornton Dial’s work is premised upon the idea of a past; and, in the 2004 sculpture that is History Refused to Die, that concept is directly juxtaposed with the near opposite of modernity. Dial does not acknowledge a future of any sort – a future is only possible when history is no longer present (hence the above), and the artist makes it a point to correctly distinguish between the two.

The first sense of structure discernable in the piece is that of a wooden fence. Plastered upon it: torn, bloodstained clothing, wire, greenery.

In cases figurative and literal alike, fences typically signify points of transition. For Black Americans, that “transition” was promised to be one from past – slavery, segregation, and racism – to future: overdue liberation. The fence, however, was not a transition. It was an impasse. Attempts to walk through it led not to the future, but to a present that could not escape history’s grasp.

The back end of Dial’s fence is where suggested juxtaposition between past and present is solidified. In stark contrast to the present inflicted upon his race by America, the artist uses the reverse side of the fence to point a rare finger in the direction of what “past” meant prior to U.S interference.

Of many symbols, the most significant is a formation of roots.

The idea of a root is a compelling one to any African prostituted by the U.S, for it represents a point beyond which there is no disgraceful history to be referenced. When Alex Haley wrote his famed 1976 narrative of the negro, he titled it Roots – not only for the fact that it constitutes a beginning, but, also, because from the root on, the magnificent tree that is the black race ought to be what is concentrated upon – not the star spangled lumberjack that vows to chop it down.

Dial was one to take a journalistic approach to his artwork. Rather than take into account only one side of the stories he reported, he looked into both the past and the present – no matter how painful – to help the public form some sort of speculation about the future.

But, for now, that future will not will not exist until we cleanse it of its past.

The fence remains an impasse.

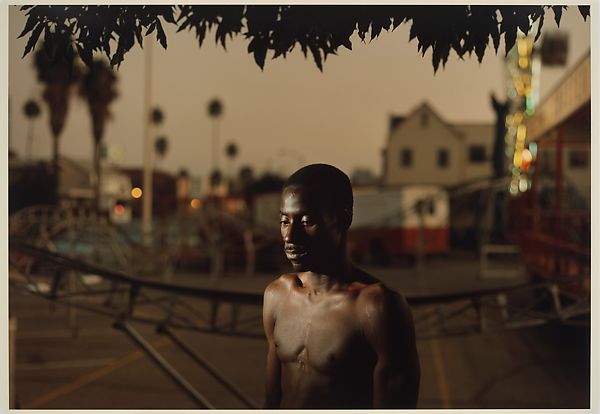

André Smith, 28 Years Old, from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, $30 – Philip-Lorca diCorcia (1991, printed 1995)

Baton Rouge was never truly at peace. For Philip-Lorca diCorcia, that was perfect.

The color-centered unrest surrounding Louisiana’s capital has, for years, been a direct illustration of injustice’s persistence in spite of illegality. 2016 saw the quality gain a nation as its witness – following the shooting death of Alton Sterling, weeks of racially charged rioting culminated in the murders of three police officers. A national conversation about race and policing was reignited, and a movement conceived.

But, twenty-five years before the cameras in Baton Rouge belonged to reporters, they belonged to photographer Philip-Lorca diCorcia. News stories were not his motive. Much like Jacob Lawrence, diCorcia sought to tell tales of humanity in its most authentic form – often juxtaposing fantasy with documentation to do so. The “Hustlers” series was an acclaimed vessel through which such truths were chronicled. At the apex of the AIDS outbreak, dozens of male prostitutes were paid their usual rates to have their pictures taken.

In this one: André Smith, Louisiana hustler, clad in nothing but his dark skin.

The shot alone evokes feelings of gloom echoed by millions of African Americans nearing the turn of the Century. Smith, unclothed, glares at the ground before him as the sun sets behind his back.

The promise of Civil Rights signed into law about 30 years prior served as the ‘light’ for minorities; it was an extension of Lincoln’s 1863 “great beacon of hope.” After a near-decade of demonstrations, assassinations, and degradation, the pen of Lyndon B. Johnson vowed to end what had been centuries of prostitution.

But – as photographed by diCorcia – decades changed nothing.

By 1999, the sun still faded, the night still loomed, and the African-American continued to stand outside with nothing on his back but his skin.

In Conversation With Kiara Ventura

Kiara Ventura is a Teen Vogue Art School columnist, independent curator, and consultant based in New York City. In addition to curating galleries like 2019’s FOR US, she also owns ARTSYWINDOW – a resource for young artists of color focused on encouraging new perspectives through creativity.

Below, please enjoy a short interview with Ms. Ventura on how the intersection between art and resistance has played out over time. The interview has been condensed for publication.

SAMUEL HYLAND: I feel that there’s a huge cultural aspect of growing up both an Afro-Latina and a Bronxite. Looking back, how did being raised in both of those spheres influence the artist you’ve become today?

KIARA VENTURA: This is a conversation that I’m constantly having with artists that I work with – you know, it’s a question about identity; how does your identity influence the work that you do? And the thing is, being Afro-Latina, being from the Bronx, and just simply being a person of color, like when you go into certain spaces, you try to find your story there – you try to find your narrative there. When I was in high school, and I began trying to find internships, museums, and galleries to visit, I often didn’t see my narrative being told. That’s what drove me to try to be a part of the art world. (The internship at the MET) really opened my eyes to the work that needs to be done in museums, and in the world in general: just more representation, people of color working in higher positions in institutions. (…) I’m grateful for my experience, because it really pushed me to do the work that I’m doing today.

SH: All in all, what role do you feel art plays in resistance? How has that taken shape throughout your career?

KV: My work is very much about curating, supporting artists, and uplifting the stories of artists of color – I mean, resistance is definitely a theme in my work, intentionally and sometimes not intentionally. I feel like anything we do as people of color that is geared towards obtaining our freedom in any way, is an act of resistance. I feel like self-care is an act of resistance, taking time off is an act of resistance, relaxing, taking a nap in the middle of the day, you know what I mean? No matter what, our work is an act of resistance, especially when we’re trying to uplift ourselves and our communities; but, in terms of like, specifically for me – and this is something, again, that I’ve been coming to, and even with the protests that are going on, you know – everyone’s like how can I help and all of these things. For me, it was just a reminder to keep doing the work that I’m doing. Since I started curating, I’ve been showing work by artists of color; that has been my goal. So I feel like that within itself is an act of resistance. I feel like a lot of artists of color tend to think “I have to make my art super literal, so people get it,” or “I have to make my art super figural,” and what I try to remind the artists that I work with is to “give yourself that space to be experimental.” Paint anything, because that’s an act of resistance, too. We don’t have to put our stories of oppression, and struggle, and all of these things at the frontline all the time.

SH: I want to talk about ARTSYWINDOW, the company you founded for artists of color. I really resonated with the mission statement of sort of pushing people to reconsider their perspectives through art. To what extent do you feel that applies to what we’re seeing in society today?

KV: A main focus of ARTSYWINDOW is definitely looking at our past, and considering our art history. I’ve been teaching art history classes through ARTSYWINDOW since 2018, and all of the classes are about artists of color. This is through the series I did with ARTSYWINDOW called AW Classroom, and with that series, I also do panel talks and conversations with contemporary artists of color, of course – because, what I think a lot of artists experience is that they may feel alone in their artistic process, or maybe they don’t have that many people to look up to, or they go to art school and they’re the only person of color in that class, you know what I mean? This experience even for me, being a curator, feels lonely – but the times when I feel the most uplifted are when I talk to someone in my community, when I talk to my mentor — because it’s hard, you know? But what I try to do with ARTSYWINDOW is teach classes, have these panel talks, share these stories of artists of color, so that we all are reminded that we have a beautiful lineage of history, and tastemakers, and entire movements behind us. Ultimately, the things that we create are in conversation with the things that they have created. So, in terms of reconsidering – yeah, I try to make the public reconsider art and their relationship with it, because that’s what the artist is doing. I feel like one of the roles that artists take on is reexamining our current society, our history, our stories, and questioning it all through their work.

SH: Going off of the theme of revolt, are there any specific art pieces that come to mind, especially in light of movements like the one we’re seeing today?

KV: Ooh . . . hmm okay, um, wait-

SH: Bonus points if they’re in the Met collection!

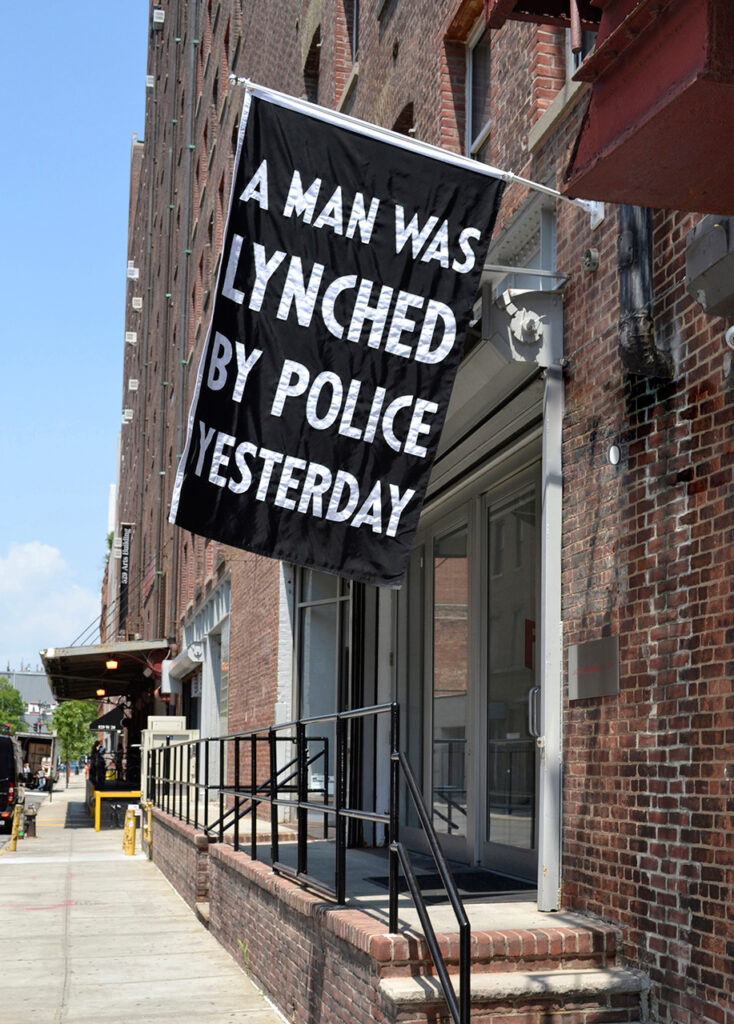

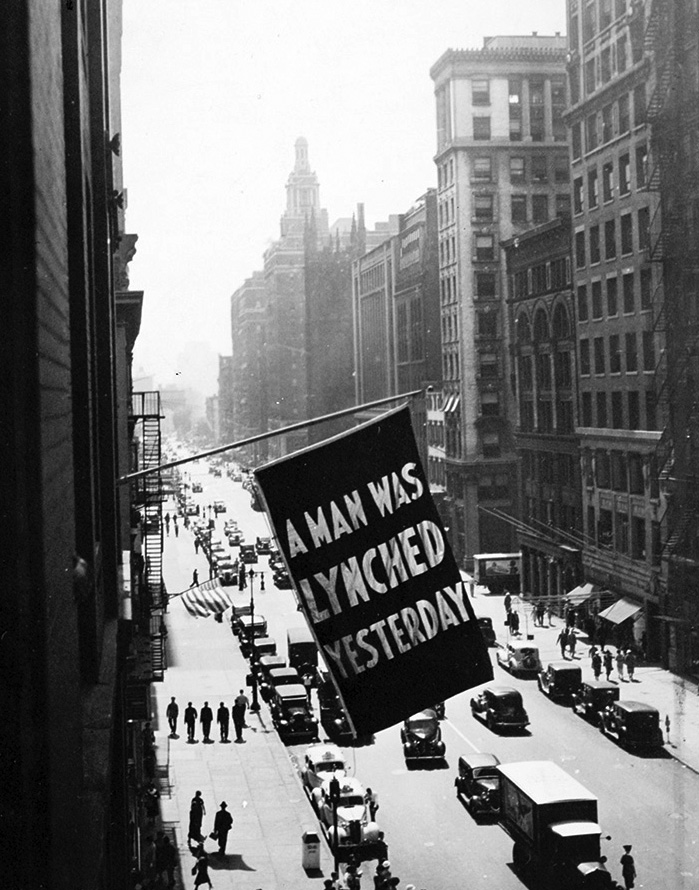

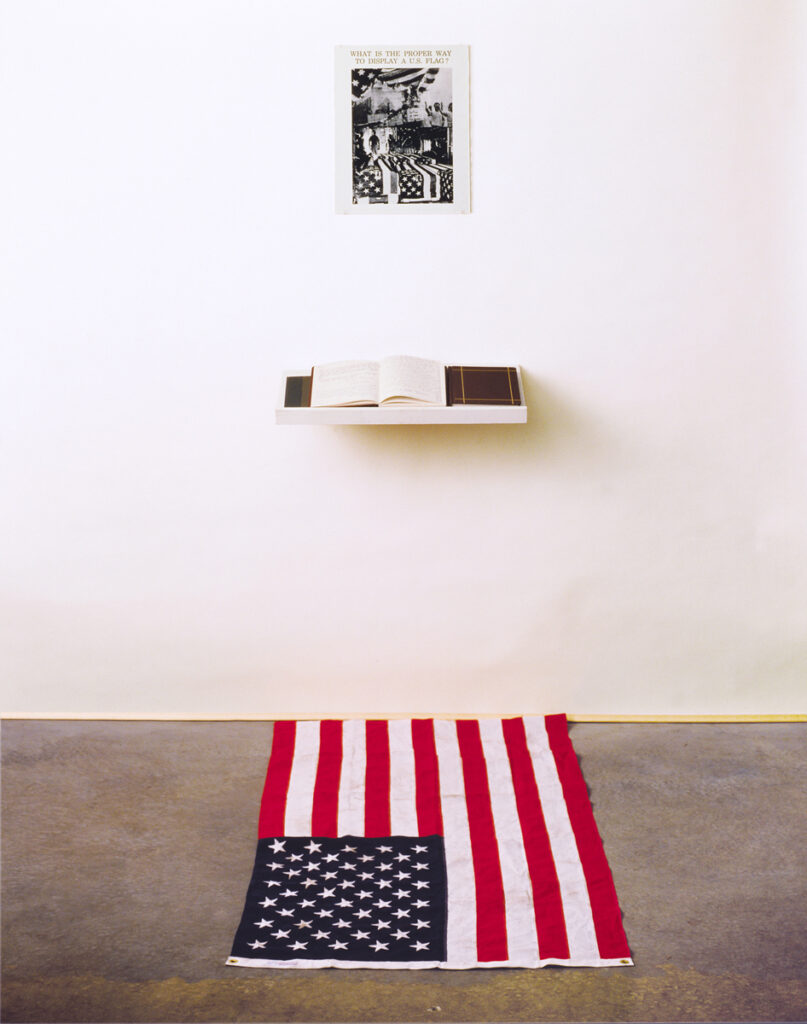

KV: Oh shoot! Oh gosh. Goodness gracious – I would definitely say all the work by Dread Scott is revolutionary; I mean, his work is literally about reconsidering American History and how America has left African-Americans out of it. So I would definitely say Dread Scott’s A Man Was Lynched By Police Yesterday is one of my favorite works. I have a class called Fuck the System where I talk about a lot of his work. Also, I’m forgetting the name of this one, but one of the first works he made as an art student, with the flag on the floor – um . . .

SH: It’s cool if it’s not coming to you right now, ha.

KV: Ha, like I need to know this! The art history student in me is like I need to know the exact name and date!

SH: That was actually going to be my next question, about your studies in art history. So, you studied art history and journalism at NYU, right?

KV: Mhm.

SH: Do you feel that having a background in both art and writing gave you more of a platform to resist in both mediums?

KV: Oh, yes, yes. I’m so happy that my curatorial practice is very much informed by the work that I do in writing and journalism. The thing is, I was writing way before I started curating. Even when I had that internship at the MET, my head was like I’m going to be a writer. I wasn’t even thinking of curating. So, I went to NYU, and in order to major in journalism I had to major in something else too, so I was like ‘that’s easy’ – Art History, because I just came fresh out of that MET internship and was like I wanna learn more. I was interviewing artists for my blog, which grew into ARTSYWINDOW and became my curatorial platform; and, because I was doing that, I got an understanding of what artists are thinking about, their needs and their wants – and to this day, that’s what I do — I’m a freelancer – I live off of curating and writing about artists of color. So just hearing these stories, and doing studio visits, and having these conversations with artists just fuels my work. It fuels me as a person, it just motivates me, it inspires me, and then that goes straight into the exhibitions that I do and the content I put out with ARTSYWINDOW.

SH: What do you think the future is for resistance through artistic mediums?

KV: I think the resistance is definitely within unity. Just me, as a young freelancer, business owner, I’m looking – you know, the thing is, like, I work with a lot of institutions in terms of putting together these shows, paying these artists, getting that funding together – and most of these institutions are white, which is where the decision making comes in. That’s where I’m like ‘okay’ – a lot of my job is also negotiating with these places and being like we need more, you know what I mean? Like if you want to work with us, and show that you have a diverse amount of exhibitions, programs, and you have artists of color and you’re supporting us, then you better come with the funds. And that’s where I come in, to redistribute the funds to artists of color. I think there’s power in that, in working internally within the institutions and holding them accountable , and that’s a big part of my job. Like if you don’t come correct, imma come at you! Because some of these people really start talking crazy. They’re like Oh, because we’re giving you this opportunity, you should be grateful. They’re at the top of the pedestal, and they’re like “you should be grateful that you’re even here”; and that’s where I’m like well you should be grateful that we’re here giving you the spice and the sauce that y’all have been needing. It’s for real though. All these institutions want to show that they’re “with the times,” and they’ll reach out to people like me to provide a diverse amount of programs, with these radical ideas and exhibitions – but you have to support me all the way. It’s either you accept my package, or you don’t.

SH: Overall, from what you’ve learned over the course of your career, your collegiate experience, and everything you’ve told me thus far, what do you make of the movement we’re seeing?

KV: I think it’s beautiful. You know, like I can’t lie , when everything was unfolding, and I was on social media, the beautiful part was that a lot of people were being more transparent and sharing their stories about what they have experienced. It’s beautiful to see on Instagram, which is a platform where everyone is tryna look good, share their vacation photos – and yeah, it’s a space of celebration, too – we love to share our successes and all of that stuff, but now it’s really a time where everyone’s being more transparent and just getting real. And I’m here for that. Because when we share our stories, we’re educating each other. And I can’t lie, also – it was a mental battle every day. When everything was unfolding, it was triggering. Like damn, I can relate to that. Or damn, I didn’t know that you went through that. And also, I’m in a place of privilege myself – I’m a light skinned Afro-Latina, you know? So it made me sort of re-examine how I use my privilege to better serve my community as well. I love how it’s bringing the community closer together, to a point where we’re communicating now more than ever. I mean, they’re not things like yeah, let’s start a whole museum off of this, or anything like that, but the conversations are starting. Beautiful things, the seeds are being planted. And yeah, it’s just creating that foundation for somethin’ to grow. Somethin’ gonna grow! Maybe like a mango tree or something, I don’t know. Somethin’ fruitful!

You can learn more about Ms. Ventura at kiaraventura.com.