There was earth in them, and they dug.

Showing at Miriam Gallery from June 10th to August 8th, There was earth in them, and they dug exists as a living study of life itself, equally reckoning with the nuances between lives lived, lives to be lived, and lives yet to come to fruition.

SAMUEL HYLAND

In Phillip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep – a harrowing 1968 sci-fi title about the few people remaining on a post-human Earth – animals transcend the primitive role of food-chain constituency: they are status symbols. Following a desolating global conflict called World War Terminus, a threateningly over-polluted atmosphere forces humans who are rich enough to escape into interplanetary being. For those who fall underneath the economic dividing line, there is no option but to remain trapped in a world that is actively rotting away. All life is an eviscerated reflection of its former prominence. Android versions of everyday creatures become collector’s items. Those well-off enough to own real animals sit at the pinnacle of the social ladder. Water, air, and organic life writ large go from infinite and overlooked, to sacred and revered.

It’s a construct that wasted little time playing itself out within urban communities at the height of the pandemic. Though the world was not definitively coming to an end, lifestyles as comfortable as many once knew them to be were – and when the resources became scarce, the excursions became plentiful. Wealth evolved into the difference between salvation and doom. Some found themselves in an uphill battle against death itself, while others enacted the same exact escapism by way of vacation. And, just as they did in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, oft-neglected facts of life (toilet paper perhaps being the most extreme case) became hallowed to those imprisoned within a dying ecosystem with not much left to offer.

When I arrive at Brooklyn’s Miriam Gallery on a humid Saturday morning in June, the first thing to register isn’t visual, but sonic: emanating from somewhere in the space is an endless auditory replay of streaming water. Miriam Gallery is modest in size. From the intersection of Bedford Avenue and S 2nd Street, it strikes one not as a sacrosanct cultural mainstay, but one of several graffiti-ridden storefronts in a churning visual expanse that winds its way monotonously down the horizon. Once beyond the glass door at its front, though, there is an intimate sense of quiet that – in conjunction with its small-scale volume – makes everything within it several times more tangible than the real world could allow. In the typical household, running water sounds like the handiwork of an irresponsible bathroom-user who has once again failed to push the tap hard enough for it to stop dripping into the sink below. Here, alternatively, the same exact sound of liquid feels viscerally sanctified; it commands your attention, then latches itself onto you in the subconscious.

“There’s an entirely new religion that’s entirely based around, like, the vision of seeing a real animal in the desert. This hope for the salvation, or continuity, of something – the hope that we haven’t destroyed everything.”

The liquid sound comes from Infosphere, a 2019 visual work by the artist Alexandra Neuman. It is several lengths more encompassing to hear the sound when it is played alongside its accompanying video: on a medium-sized TV screen suspended on the wall, two human figures covered from head to toe in pale bodysuits sit somberly in San Diego’s Anza Borrego desert. The characters are connected to each other solely by a shared feeding tube-esque pipe that runs from one face to the next, dipping into a modest pool of water set in between. Their mannerisms are mild and mournful. One figure seems to make sporadic bowing motions, while the other, relatively still, is ostensibly downcast. There is zero sound except for the liquid.

As we stop to discuss Infosphere during a walkthrough of the exhibition, curator Nicole Kaack is quick to ask whether I have read Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep.

“Only the people who can’t afford to get off Earth are on Earth- but there’s such a scarcity of real animals because everything else has been wiped out by the total desolation, how badly the environmental crisis has progressed,” she starts, when I say that I haven’t. In the background, the two figures are beginning to look more and more like members of an obscure religious sect, either outdated and obsolete, or futuristic and beyond modern understanding. The water feels like a shibboleth that one will either fully devote themself to or holistically ignore – no in-between. Again, much like they do in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, the most primitive natural extensions of Earth are finding ways to become sacred.

Kaack continues. “There’s an entirely new religion that’s entirely based around, like, the vision of seeing a real animal in the desert. This hope for the salvation, or continuity, of something – the hope that we haven’t destroyed everything.”

I nod in agreement and we fade to silence. The water seems to get louder and louder.

Showing at Miriam Gallery from June 10th to August 8th, There was earth in them, and they dug exists as a living study of life itself, equally reckoning with the nuances between lives lived, lives to be lived, and lives yet to come to fruition. The exhibition is influenced in major part by the formative science fiction literature that shifted attitudes toward Earth as a sentient being, rather than non-living space matter. “Science fiction and fantasy are replete with depictions of a sentient earth, with landscapes that share a single biological cycle with the entities that inhabit them,” the opening paragraph of its press release reads. “In Stanislaw Lem’s 1961 Solaris, an alien sea communicates with human space explorers through liquid dioramas; in Orson Scott Card’s Lusitania, mammal-like creatures undergo a sacrificial process by which they become seedlings in a network of conscious trees; and in Octavia Butler’s Dawn, the central character’s first struggle is to escape the organic and womb-like walls of a living spaceship. Likewise, the artists in There was earth in them, and they dug consider fictions and realities by which humans become seamlessly part of the environment around them, as water passing into the sea.”

Dispersed throughout the gallery’s front room is work by Umico Niwa, the Japanese-born multi-disciplinary artist whose output explores concepts of gender and sexuality, alongside the intersections of each with the reproductive system of nature as its own being. It’s an area of study that lives closely with Niwa: some years ago, she underwent a bilateral orchiectomy surgery that rendered her permanently unable to reproduce by natural means. The procedure left her with a sensation of phantom limb. She started to have vivid dreams, where bodily elements she could no longer control turned into trees. In her waking hours, her mind found itself haunted by similarly endless veins of introspection. There came a point where the circuit needed to close. “She ended up contacting the clinic in Japan where she had the surgery done,” Kaack said, “and they told her actually that her biological waste had been burned and then deposited in a reserve for young sapling trees.”

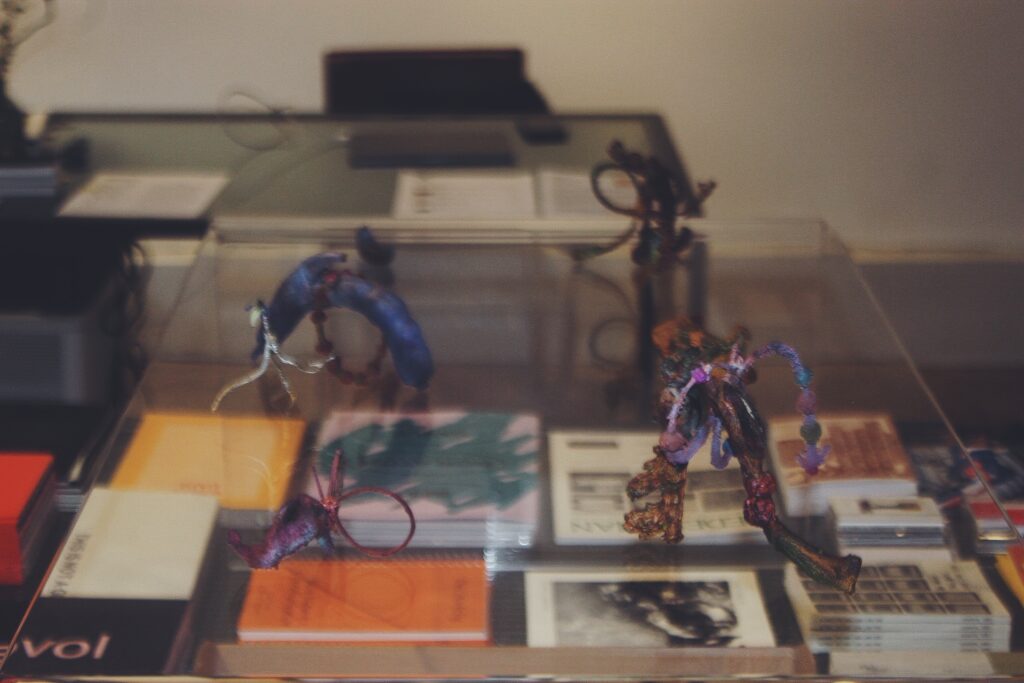

Inspired by both a state of mourning for the offspring she could never produce, and a newfound knowledge of where her discarded body parts rested, she set out to create an eclectic set of works that put the two factors in conversation. There are several pieces of hers dispersed throughout the gallery, and all take on the same reproductive theme – look at one assemblage of her works set atop a glass book container, for instance, and the first thing it all may visually translate to is a quadruplet of colorful phalluses. Yet, exclusively upon further examination, a viewer comes to realize two things: one being that the forms are primarily constructed from natural produce (I’m shocked when Kaack points out a tamarind that seems to be hiding in plain sight). And, secondly – perhaps most significant in this case – they are all made in the likeness of baby shoes. In some parts of America, agreed upon by Kaack and I to definitely not include Brooklyn, New York, it is tradition to memorialize a newborn baby’s first walking shoes by means of display cases, casts, or other permanent means. With this piece, Niwa takes defiant ownership of the exact ritual many would deem her unfit to partake in: her offspring is not human – it is both natural and intellectual. In her case, a human being’s reproductive organs have been left to sit amidst the roots of a growing plant; two inherently opposite reproductive cycles have been made to coexist. Yes, it is instinctive to mourn for what isn’t – but, Niwa asks, why not also revel in the hybrid that is?

“There is definitely the sensation of a living being talking to you. And whether from the humming in the corner, the reconfigured scaling of the room, or the obscure nature of the pieces (buckets of steaming water, unorthodoxly-crafted plants that seem to be standing on hind legs, etc) the message registers as a threat.”

The exhibition also asserts that in any fruitful conversation about life, it is necessary for there to be an honest reckoning with both the beautiful and the ugly – not only for sake of clarity within oneself – but equally because the two may intersect: sometimes the beautiful is ugly. Sometimes the ugly is beautiful. And either way, whether you acknowledge it or not, it lives right in front of your face. Walking into Miriam Gallery, Clare Koury’s Hopper is, although very likely the largest piece in terms of mass, one that I very easily miss. It’s a clear plastic pipe that connects to the metal one already built into the gallery’s walls. The fixture is completely stuffed with trash. Cheetos wrappers. Mangled aluminum soda cans. Broken beads. Dusty papers.

All in all, there is a strange beauty that emanates from a display that is quite literally preserved garbage: comfort exists within the fact that it doesn’t care what you think. One does not critique rubbish; one disposes of it. But to insert what is, arguably, the most repulsive human product into something like a polished art gallery, is to flip the construct onto its head. There is rarely such a thing as perfection, and more often than not, it is the imperfection peeking through the cracks that is the true spectacle.

Talking to Kaack in front of the piece, it comes up that the time period during which Hopper was created – a pre-pandemic 2019 – makes it all the more reliable in its anti-perfectionist messaging. My initial guess that it was constructed as a form of science fair-esque quarantine documentation was particularly easy to reach, because along with the outbreak, there has come a commercial rebranding of honesty. Kaack and I discuss a recent New Yorker cover, for instance, in which a relatably unkempt woman is illustrated smiling, well-dressed from the waist-up, for an online meeting, while the rest of her bedroom surroundings tell a far messier story. It quickly went viral for its earnest positioning. The cover sits among many indicators of a noticeable shift in culture that predicates itself upon the “new normal” as a selling point, a mantra, a form of common ground.

With Koury’s piece, dynamically, the influence of such newfound candor could not yet have existed to serve as inspiration. Removing the overarching crux of a pandemic means removing a cultural obligation to produce some form of evidence. Hopper is, before anything else, a study of life in tandem with planet Earth. Just like Niwa accomplishes via her organic phalluses, it examines the waste we spew as human beings, holds it up to a microscope, and sows seeds for speculation as to what it will produce without us – even if the offspring is, after all, something as simple as our collective legacy.

“-food rots, paper degrades, pencil marks fade, digital data decays, technologies obsolesce and become unreadable. But people continue to make them because it’s a way to reach out to an uncertain future and let them know ‘I was here,’” Koury mused in a 2019 interview. “So in that gesture there’s this idea of futility, but also great optimism and hope. I guess the only real difference between putting something in a time capsule and putting it in a landfill is the hope that someone will come back for what you’ve left behind.”

With the science fiction-stemmed idea of a sentient Earth, there is also the reactionary speculation that it is talking to us. It’s a silent motif that constantly introduces itself in the gallery’s second room, a slightly darker expanse a few steps away from the bright, window-lit foyer. Passing through the entryway, one feels a tangible shift in the energy present – there is a sudden shadowiness to it that quickly envelops the artworks in mystery; from a corner of the room, an eerie, muffled, indeterminate hum phases in and out of earshot; whereas most of the pieces in the front room were at eye-level, the majority of the works here are stationed on the floor. It begins to feel a lot like Alice In Wonderland. The conventional pathway has led you down an undetectable rabbit hole, and now you’re a giant in a civilization full of smaller things that you aren’t quite used to.

“I wanted this room to have a different center of gravity,” Kaack mentions as we walk in. “Having these works the places they are, you’re very careful, and aware of your body and space in a different way.”

There is definitely the sensation of a living being talking to you. And whether from the humming in the corner, the reconfigured scaling of the room, or the obscure nature of the pieces (buckets of steaming water, unorthodoxly-crafted plants that seem to be standing on hind legs, etc) the message registers as a threat.

Yet – just like the first gallery made clear – it takes a willingness to shed one’s humanistic tunnel-vision to absorb the fullness of the environment offered.

For the first few minutes that Kaack walks me through the back room, I am feeling increasingly terrified by whatever living thing absolutely must be lurking underneath the floorboards somewhere. My focus is strictly on the ground. It feels like my first day of high school — the more I feel that my surroundings are out to get me, the more transfixed my eyes are to my shoes; and the more transfixed my eyes are to my shoes, the more I feel like my surroundings are out to get me.

The only works I notice for some time are the ones that happen to fall in line with my downward glare.

Then, at some point, Kaack gestures toward the ceiling: strewn about at various locations across light fixtures, upper walls, and beams, are more of Nawi’s colorful flower petals. They’re a striking beacon within an environment that seems to dance along the edges of dystopia: the sphere of gravity may have changed, but the persistence of life has not.

Talking to Kaack in a cluttered backroom of Miriam Gellery after our walkthrough, I begin speaking of the exhibition’s ceremonial opening – a jam-packed Thursday evening event that featured pleasantly unconventional music from a live band – with a particular focus on how unsettling I think the content could have been for first-time visitors. I start talking about how Niwa’s post-procedure work is, in part, mournful. She is quick to retort.

“Well it’s not all doom and gloom,” she starts. “I would argue that Umico’s works are, to some extent, mourning, but they’re also a kind of celebration. There’s a sense of becoming one with something else, or reproducing in different ways – so if she can no longer have children that are biologically her own, there’s still this sense of creation that offers a new beginning.”

The sentiment rings true with not only Niwa’s work, but the entire exhibition writ large: the beauty is existent, but you can only find it if you look. It seeps through the cracks in figures like Hopper, where you would never know that there’s a transparent pipe of legacy-leaving garbage if you don’t look at the piping system for an extra second, and in vast arrays like the second room, where you can so easily get sucked into the gravitational pull of the ground that you never realize the divinity in the ceiling. Being alive in a sentient Earth means being eligible for communication with it. But the Earth can only speak if you’re willing to listen to it.

…And it’s a journey we all have to embark on by ourselves. One of the most striking displays in the second room is a heap of dirt – underneath which the aforementioned eerie, indeterminate hum bellows – stationed in front of a television screen in the leftmost corner. On the screen, Alexandra Neuman’s An Ecology of Mind (2020) is playing. It’s a visual documentation of 32 human subjects, each of which Neuman had buried neck-deep in similar dirt to the heap on the ground, for a set amount of time. Some of the subjects appear to be jittery, restless eyes jumping about in nervous arc after nervous arc. Others seem to gaze away from the camera, perhaps fixating their focus on one external point as if to alleviate the awkwardness of their plight. This isn’t artificial soil manufactured specifically for the experiment – it’s the real deal – and one wouldn’t be unwise to bet that worms, ants, and slugs are keeping the submersed subjects just as much company as their thoughts.

“This installation is the compiled documentation of thirty-two individuals immersed inside of a hole in the ground as part of an investigation of the co-emergent relationship between body, mind, and world, and the recursive notion of matter thinking about matter thinking about matter,” Neuman’s own description of the project reads. “While the body is undergoing a hyper-sensory experience, the resulting image isolates a disembodied head or continually rendering consciousness.”

Talking with Kaack, the idea of death is quick to come up. It’s a memento mori. The people are practically living in their own graves.

If you listen closely, standing by the work, you can almost make out a collection of human voices.

“The spoken murmurings you can hear are reflections,” Kaack explains. As a culmination to the project, Neuman interviewed all 32 subjects for closing opinions. Their responses play, non-stop, in the backdrop of the eerie hum that overtakes it all. “But it kind of has this indistinct quality – like, you can’t really hear what they’re saying.”

Just like both the death that such a display evokes, and the life fostered by the exhibition hosting it, the only way to know what it’s like is to experience it yourself.